Battle of Caseros

The Battle of Caseros was fought near the town of El Palomar, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, on 3 February 1852, between the Army of Buenos Aires commanded by Juan Manuel de Rosas and the Grand Army (Ejército Grande) led by Justo José de Urquiza. The forces of Urquiza, caudillo and governor of Entre Ríos, defeated Rosas, who fled to the United Kingdom. This defeat marked a sharp division in the history of Argentina. As provisional Director of the Argentine Confederation, Urquiza sponsored the creation of the Constitution in 1853, and became the first constitutional President of Argentina in 1854.

| Battle of Caseros | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Platine War and the Argentine Civil Wars | |||||||

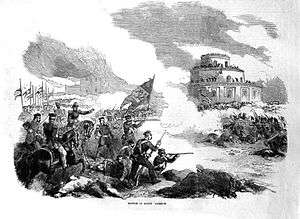

Lithography of the Brazilian 1st Division during the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Ejército Grande |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

24,000-28,000 (3,500 Brazilians & 1,500 Uruguayans) 50 guns |

22,000-23,000 60 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 600 killed or wounded |

1,500 killed or wounded 7,000 captured | ||||||

Background

Rosas had declared war on Brazil in 1851, which led to the signing of a treaty, on 21 November 1851, among the governments of Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Uruguay and the Brazilian Empire. In compliance with the treaty, Urquiza led a joint army and crossed Morón creek, positioning his forces in Monte Caseros.

The battle

Rosas' forces comprised 10,000 infantry troops, 12,000 cavalrymen and 60 guns. Among his captains were Jerónimo Costa, who defended Martín García island from the French in 1838; Martiniano Chilavert, a former opponent of Rosas who defected when his fellows allied themselves with foreigners; Hilario Lagos, veteran from the campaign against the Indians of 1833.

Due to desertion, especially that of General Ángel Pacheco and poor morale, several historians and military analysts reckon that for Rosas the battle was lost even before it started. However, his opponent also suffered from desertions like that of the Regimiento Aquino, a regiment composed by soldiers loyal to Rosas, who murdered their captain Pedro León Aquino and joined the Rosist army.

Urquiza's army was 24,000-men strong, among them 3,500 Brazilians and 1,500 Uruguayans, and 50 guns. Only the Brazilians were professional soldiers. Urquiza did not conduct the battle: each chief was free to fight as they saw fit. Urquiza himself led a charge against the enemy left in front of their cavalrymen from Entre Ríos.

Meanwhile, the Brazilian infantry, supported by a Uruguayan brigade and an Argentine cavalry squadron seized the Palomar, a circular building near the right of the Rosist line and used for pigeon breeding, extant to this day. After both flanks collapsed only the center under Chilavert's command continued the fighting, reduced to an artillery duel that lasted until he ran out of ammunition.

The armies clashed in the proximities of the ranch of the Caseros family, in Buenos Aires province; the battlefield was located between the present-day railway stations of Caseros and Palomar, the area is now occupied by the Colegio Militar de la Nación (National Military College), a military academy.

The whole battle lasted about three hours, after which Rosas was wounded in a hand and fled; he wrote a resignation, and a few hours later he boarded the British frigate HMS Centaur towards exile in Southampton.

Aftermath

Urquiza's triumph terminated the 20-year term of Rosas as Governor of Buenos Aires and de facto ruler of the Argentine Confederation. Within a few days, Urquiza's troops entered the city of Buenos Aires without further resistance. The President of the Superior Tribunal, Vicente López y Planes, was appointed interim governor.

Sources

- Gálvez, Manuel (1949). Vida de Juan Manuel de Rosas. Buenos Aires: Editorial Tor.