Battle of Ayn al-Warda

The Battle of Ayn al-Warda (Arabic: مَعْرَكَةعَيْن ٱلْوَرْدَة) was fought in early January 685 between the Umayyad army and the Penitents (Tawwabun).[lower-alpha 1] The Penitents were a group of pro-Alid[lower-alpha 2] Kufans led by Sulayman ibn Surad, a companion of Muhammad, who wished to atone for their failure to assist Husayn ibn Ali in his abortive uprising against the Umayyads in 680. Pro-Alid Kufans had urged Husayn to revolt against the Umayyad caliph Yazid but then failed to assist him when he was killed in the Battle of Karbala in 680. Initially a small underground movement, the Penitents received widespread support in Iraq after the death of Yazid in 683. They were deserted by most of their supporters shortly before the departure to northern Syria where a large Umayyad army under the command of Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad was preparing to launch an assault on Iraq. In the three-day long battle that ensued at Ras al-'Ayn, the small Penitent army was annihilated and its senior leaders, including Ibn Surad, were killed. Nevertheless, this battle proved to be a forerunner and source of motivation for the later more successful movement of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi.

Background

The first Umayyad caliph Muawiyah's designation of his son Yazid as heir in 676 had been opposed by many who resented his rise to the caliphate. Hereditary succession was alien to Arab custom, where the rulership passed within the wider clan, and Islamic principles, where the supreme authority over the Muslim community was not the possession of any man. Opposition was led especially by the sons of a few prominent companions of Muhammad, who, according to Islamicist G. R. Hawting, could lay "some claim to be considered as caliphal candidates" by virtue of their descent.[4] They refused to be bribed or cajoled into acknowledging Yazid.[5][4]

After Muawiyah's death in April 680, Yazid ordered the governor of Medina, where all his opponents were based, to obtain their obedience. Of these, Husayn ibn Ali and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr evaded the governor and escaped to Mecca.[6][7] There Husayn received letters from the Iraqi garrison town of Kufa with the invitation to revolt against Yazid and regain his rightful place as the leader of the Muslim community which his father, Ali (r. 656–661), had previously held. Husayn sent his cousin Muslim ibn Aqil to prepare the ground for his arrival. Ibn Aqil sent back a favorable report, urging Husayn to depart for Kufa. Shortly afterwards, Ibn Aqil was apprehended and executed by the Umayyad governor Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad and his supporters suppressed. Unaware of the situation, Husayn left for Kufa, but was intercepted and killed just outside of the town. His expected support never arrived.[8][9]

Belligerents

Penitents

Some of Husayn's supporters in Kufa, who called themselves Penitents, blamed themselves for the disaster and decided to atone for their perceived sinful abandonment of their leader. Considering the prohibition of suicide in Islam, they decided to sacrifice themselves in a fight against the perpetrators of the massacre, to achieve salvation and martyrdom. Sulayman ibn Surad, a companion of Muhammad and old ally of Ali, was chosen as leader of the movement.[10] Meanwhile Yazid died in 683 and Umayyad authority collapsed across the Caliphate, giving rise to the civil war known as the Second Fitna. Ibn Ziyad was expelled from Iraq and he fled to Syria. This afforded the Penitents their opportunity to act. A large-scale recruiting campaign was launched which met with considerable success and 16,000 men joined the movement. On the day of departure though, only 4,000 men arrived,[11] of whom another 1,000 left on the way.[12] Undeterred, the Penitents moved up the Euphrates River towards the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia). They were all mounted and well-

equipped.[13]

Umayyads

The short reign of Yazid's successor Muawiyah II ended with his death after a few weeks. With no suitable Sufyanid[lower-alpha 3] candidate to succeed him, Umayyad loyalists in Syria chose Marwan ibn al-Hakam, a cousin of Muawiyah I, as the caliph. Marwan's accession was challenged by several north-Syrian tribes led by Banu Qays who supported the cause of the Mecca-based counter-caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.[14] Marwan defeated them with a small army of 6,000 at the Battle of Marj Rahit (684). Following the victory, he sent Ibn Ziyad back to Iraq. Realizing that his forces were not strong enough to reconquer the province, Ibn Ziyad set out to strengthen the Umayyad army by recruiting from various Syrian Arab tribes, which included even the tribes that had opposed Marwan at the Battle of Marj Rahit. By the time he faced the Penitents, Ibn Ziyad had raised a formidable army of Syrians.[15]

Battle

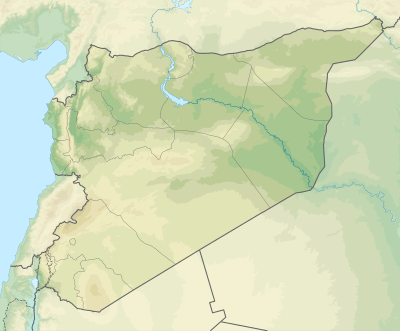

On their march towards Syria, the Penitents made a short stay at al-Qarqisiya. The Qaysi refugees from the Battle of Marj Rahit of the previous year had entrenched themselves there and aided the Penitents with supplies. The Qaysi chief Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi informed Ibn Surad of the Umayyad troops' location and advised him to march on Ayn al-Warda (identified with modern Ras al-Ayn) and arrive there before the Umayyads, as the town could be used as a base of operations in the arid steppes. Given the large numerical disparity, Zufar urged him to avoid a pitched battle and instead divide his cavalry into small detachments and conduct constant skirmishes against their flanks, "firing arrows at them and thrusting at them in an open space for they outnumber you and you cannot be sure that you will not be surrounded".[16] Noticing the absence of infantry in the Penitents' force, Zufar also advised to pair the detachments so that one could fight mounted and the other fighting on foot when needed. Despite showing sympathy, Zufar refrained from joining the Penitents outright, seeing no hope in their endeavor.[16] Nevertheless he offered Ibn Surad to stay in al-Qarqisiya and fight the Umayyads alongside him, but Ibn Surad refused.[17]

Following Zufar's advice, the Penitents camped outside Ayn al-Warda, with the town in their rear. They rested for five days before the Umayyad army arrived. The total strength of the latter was 20,000, but it was divided into two units due to disputes between its two field commanders.[18] Some 8,000 troops were under the command of Shurahbil ibn Dhi'l-Kala, and the rest were under Husayn ibn Numayr. Shurahbil arrived first, ahead of Ibn Numayr, and made camp.[19] The Penitents attacked him and his troops fled.[18][19] The next day, Ibn Numayr arrived with his troops. He called on the Penitents to surrender, who in turn demanded the surrender of the Umayyad army and the handing over of Ibn Ziyad, the supreme commander of the Umayyad forces, to be executed for his involvement in the death of Husayn. The battle began on Wednesday, 4 January.[lower-alpha 4] Ibn Surad divided the Penitents into three groups, sending two to attack the Umayyad flanks, while he himself remained in the center. On the first day, the Penitents were able to repel the Umayyads, but on the next day, Ibn Ziyad sent Shurahbil back to fight under the command of Ibn Numayr, and the numerical superiority of the Umayyad army began to prevail. Despite holding the ground, the Penitents suffered severe losses.[20] On the third day of the battle, they were completely surrounded. Ibn Surad ordered his men to dismount and advance on foot to engage in one-on-one combat. The Umayyad army started raining arrows on them and the Penitents were almost annihilated. Ibn Surad fell to an arrow shot, and of the remaining four commanders, three were killed in quick succession. Finally, the Penitents' banner passed to the last commander, Rifa ibn Shaddad.[21] At this point, the Penitents received the news that their supporters from al-Mada'in and Basra were on the way to join them,[22] but they had been completely destroyed by now, so instead of waiting for the reinforcements, Rifa retreated with a few survivors and escaped to al-Qarqisiya during the night.[21]

Aftermath

The small number of Penitents who survived felt remorse for not having fulfilled their vows of sacrifice.[13] They went over to join another pro-Alid leader, Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, who had earlier been prevented by the Umayyad governor from assisting Husayn in the Battle of Karbala. Mukhtar had been critical of the Penitents movement for its lack of organization and political program. With Ibn Surad gone, Mukhtar became the undisputed leader of the pro-Alid Kufans. He had long-term plans and a more organized movement; he appropriated the Penitents' slogan of "Revenge for Husayn", but also advocated for the establishment of an Alid caliphate in the name of Ali's son Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah.[23] In contrast to the Penitents, which had been a purely Arab movement, Mukhtar also appealed to local non-Arab converts (mawālī). In addition, he was able to win over an influential military commander and the chief of the Nakha tribe, Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar.[24] With his combined forces, he seized Kufa, and consequently its eastern and northern dependencies, in October 685. Later he sent a considerably large and professional army of 13,000, which consisted mostly of infantry, under Ibn al-Ashtar, to fight the Umayyads. Ibn al-Ashtar destroyed the Umayyad army at the Battle of Khazir and killed Ibn Ziyad, Ibn Numayr, and Shurahbil.[25] Mukhtar controlled most of Iraq, parts of the Jazira, Arminiya, and parts of western and northern Iran (Adharbayjan and Jibal),[26][27] before he was killed by the Zubayrid governor of Basra Mus'ab ibn al-Zubayr in April 687.[28]

Notes

- The primary source of the Penitents movement is the work of the Iraqi historian Abu Mikhnaf (died 774).[1][2] According to historian Gernot Rotter, the account of Abu Mikhnaf, who is generally considered reliable, is not entirely authentic in this regard.[3]

- Political supporters of the fourth caliph Ali and his descendants (Alids).

- Umayyads of the line of Muawiyah and Yazid; descendants of Abu Sufyan

- According to Rotter, this date is fictitious and the battle would have been fought in the summer of 685.[3]

References

- Wellhausen 1901, p. 74.

- Rotter 1982, p. 93.

- Rotter 1982, p. 98.

- Hawting 2000, p. 46.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 140–145.

- Hawting 2000, p. 47.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 145–146.

- Daftary 1990, pp. 49–50.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 146–147.

- Halm 1997, pp. 17–18.

- Daftary 1990, p. 51.

- Jafri 2000, p. 217.

- Wellhausen 1901, p. 73.

- Donner 2010, pp. 182–183.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 32.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 27–28.

- Jafri 2000, pp. 217–218.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 28.

- Hawting 1989, p. 143.

- Hawting 1989, p. 144.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 28–29.

- Hawting 1989, p. 147.

- Donner 2010, p. 183.

- Daftary 1990, p. 52.

- Wellhausen 1901, p. 84.

- Donner 2010, p. 185.

- Zakeri 1995, p. 207.

- Donner 2010, p. 185–186.

Sources

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37019-6.

- Donner, Fred M. (2010). Muhammad and the Believers, at the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawting, G.R., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XX: The Collapse of Sufyānid Authority and the Coming of the Marwānids: The Caliphates of Muʿāwiyah II and Marwān I and the Beginning of the Caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, A.D. 683–685/A.H. 64–66. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-855-3.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Halm, Heinz (1997). Shia Islam: From Religion to Revolution. Translated by Allison Brown. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 1-55876-134-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jafri, S. M. (2000). The Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195793870.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rotter, Gernot (1982). Die Umayyaden und der zweite Bürgerkrieg (680-692) (in German). Wiesbaden: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft. ISBN 9783515029131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wellhausen, Julius (1901). Die religiös-politischen Oppositionsparteien im alten Islam (in German). Berlin: Weidmann'sche Buchhandlung. OCLC 453206240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

- Zakeri, Mohsen (1995). Sasanid Soldiers in Early Muslim Society: The Origins of 'Ayyārān and Futuwwa. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-03652-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)