Battle at Chignecto

The Battle at Chignecto happened during Father Le Loutre's War and was fought by 700 troops made up of British regulars led by Charles Lawrence, Horatio Gates, Rangers led by John Gorham and Captain John Rous led the navy.[2] This battle was the first attempt by the New Englanders to occupy the head of the Bay of Fundy since the disastrous Battle of Grand Pré three years earlier. They fought against a militia made up of Mi'kmaq and Acadians led by Jean-Louis Le Loutre and Joseph Broussard (Beausoliel). The battle happened at Isthmus of Chignecto, Nova Scotia on 3 September 1750.

| Battle at Chignecto | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Father Le Loutre's War | |||||||

Charles Lawrence | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Mi'kmaq militia Acadian militia |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Jean-Louis Le Loutre Louis de La Corne Joseph Broussard (Beausoliel) Chief Étienne Bâtard |

Charles Lawrence John Gorham Captain John Rous Horatio Gates Captain William Clapham John Salusbury Joseph Gorham Joshua Winslow John Brewse (wounded)[1] Francis Bartelo † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300 Mi'kmaq and Acadian militia | 700 British regulars and New England Rangers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 20 killed | ||||||

Historical context

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. By the time Cornwallis had arrived in Halifax, there was a long history of the Wabanaki Confederacy (which included the Mi'kmaq) protecting their land by killing British civilians along the New England/ Acadia border in Maine (See the Northeast Coast Campaigns 1688, 1703, 1723, 1724, 1745, 1746, 1747).[3][4][5]

To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day Shelburne (1715) and Canso (1720). A generation later, Father Le Loutre's War began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[6]

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (Fort Edward); Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Cobequid remained without a fort.)

After the raid in Dartmouth in 1749, on October 2, 1749, Cornwallis offered a bounty on the head of every Mi'kmaq. He set the amount at the same rate that the Mi'kmaq received from the French for British scalps. As well, to carry out this task, two companies of rangers were raised, one led by Captain Francis Bartelo and the other by Captain William Clapham. These two companies served alongside that of John Gorham's company. The three companies scoured the land around looking for Mi'kmaq.[7] After the destruction of Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg, Nova Scotia), the Siege of Grand Pre was the first recorded conflict after Cornwallis' bounty proclamation.

The battle

.png)

On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in getting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.[8] (According to the historian Frank Patterson, the Acadians at Cobequid also burned their homes as they retreated from the British to Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia in 1754.[9]) Lawrence retreated, but he returned in September 1750.

On September 3, 1750 Captain John Rous, Lawrence and Gorham led over 700 men (Including the 40th and 45th Regiment of Foot) to Chignecto, where Mi'kmaq and Acadians opposed their landing.[10] They had thrown up a breastwork from behind which they opposed the landing. They killed twenty British, who in turn killed several Mi'kmaq. The Mi'kmaq and Acadians killed Captain Francis Bartelo in the Battle at Chignecto.[11][12] Le Loutre's militia eventually withdrew to Beausejour, burning the rest of the Acadians' crops and houses as they went.[13]

Aftermath

On 15 October (N.S.) a group of Micmacs disguised as French officers called a member of the Nova Scotia Council Edward How to a conference. This trap, organized by Étienne Bâtard, gave him the opportunity to wound How seriously, and How died five or six days later, according to Captain La Vallière (probably Louis Leneuf de La Vallière), the only eye-witness.[14] After the battle, the British built Fort Lawrence at Chignecto and the Mi'kmaq people and Acadians continued with numerous raids on Dartmouth and Halifax.

Gallery

Monument to a village that was burned during the Battle at Chignecto

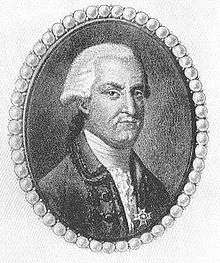

Monument to a village that was burned during the Battle at Chignecto Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne, Commander at Beausejour

Louis de la Corne, Chevalier de la Corne, Commander at Beausejour Horatio Gates fought in battle

Horatio Gates fought in battle Joshua Winslow - fought in battle

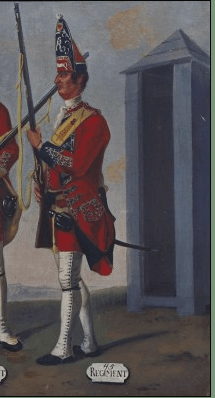

Joshua Winslow - fought in battle 45th Regiment of Foot By David Morier, 1751

45th Regiment of Foot By David Morier, 1751

References

Endnotes

- Sutherland, Maxwell (1979). "Brewse, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Salsbury's journal re: Gates

- Scott, Tod (2016). "Mi'kmaw Armed Resistance to British Expansion in Northern New England (1676–1761)". Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. 19: 1–18.

- Reid, John G.; Baker, Emerson W. (2008). "Amerindian Power in the Early Modern Northeast: A Reappraisal". Essays on Northeastern North America, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of Toronto Press. pp. 129–152. doi:10.3138/9781442688032. ISBN 978-0-8020-9137-6. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442688032.12.

- Grenier (2008), pp. 154-155.

- Grenier (2008); Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 19.

- Gentleman's Magazine Vol 20 July 1750 p. 295

- Frank Harris Patterson. History of Tatamagouche, Halifax: Royal Print & Litho., 1917 (also Mika, Belleville: 1973), p. 19

- London Magazine, 1750, p. 291

- Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 19; Griffiths (2005), p. 391

- p. 160

- Grenier (2008), p. 159.

- Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Bâtard, Étienne". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Primary Sources

- Letters concerning the Battle of Chignecto. 1750.

- London Magazine, 1750, p. 291

- London Magazine. Vol. 19. 1750. p. 521

- The London magazine, or, Gentleman's monthly intelligencer ... v.21 1752, p. 359

- The journal of Joshua Winslow, recording his participation in the events of the year 1750 memorable in the history of Nova Scotia

Literature cited

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Landry, Peter. The Lion & The Lily. Vol. 1. Victoria: Trafford, 2007.

- Murdoch, Beamish (1866). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. II. Halifax: J. Barnes. pp. 166–167.

- Rompkey, Ronald, ed. Expeditions of Honour: The Journal of John Salusbury in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1749-53. Newark: U of Delaware P, Newark, 1982.