Teke people

The Teke people, or Bateke also known as the Tyo or Tio, are a Bantu Central African ethnic group that speak the Teke languages. Its population is situated mainly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo, with a minority in Gabon. Omar Bongo, who was President of Gabon in the late 20th century, was a Teke.[1]

Ethnography and traditions

The name of the tribe shows what the occupation of the tribe was: trading. The word teke means 'to buy'. The economy of the Teke is mainly based on farming maize, millet and tobacco, but the Teke are also hunters, skilled fishermen and traders. The Teke lived in an area across Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon. The mfumu was the head of the family and his prestige grew as family members increased. The Teke sometimes chose blacksmiths as chiefs. The blacksmiths were important in the community and this occupation was passed down from father to son. In terms of life of the Teke, the village chief was chosen as religious leader, he was the most important tribal member and he would keep all the potions and spiritual bones that would be used in traditional ceremonies to speak to the spirits and rule safety over his people.

Teke masks are mainly used in traditional dancing ceremonies such as wedding, funeral and initiation ceremonies of young men entering adult hood. The mask is also used as a social and political identifier of social structure within a tribe or family. The Teke or Kidumu people are well known for their Teke masks, which are round flat disk-like wooden masks that have abstract patterns and geometric motifs with horizontal lines that are painted in earthly colors, mainly dark blue, blacks, browns and clays. The traditional Teke masks all have triangle shaped noses. The masks have narrow eye slits to enable the masker to see without being seen. They have holes pierced along the edge for the attachment of a woven raffia dress with feathers and fibers. The mask is held in place with a bite bar at the back that the wearer holds in his teeth. The dress would add to the mask's costume and conceal the wearer. The masks originate from the upper Ogowe region.

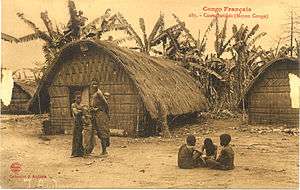

The French first arrived in what is now the Republic of Congo in the 1880s, and occupied the Congo until 1960. During this colonial period, traditional Teke ceremonies were very few. Under the French, the Teke people suffered heavily from colonial exploitation. The French government was gathering land for its own use and damaging traditional economies, including massive displacement of people. The Teke Kingdom signed a treaty with the French in 1883 that gave the French land in return for protection. Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza oversaw French interests. A small settlement along the Congo River was renamed Brazzaville and eventually became the federal capital of French Equatorial Africa. In the 1960s the Teke people started to gain back their independence and traditional life started to flourish once again.

Notable Bateke and notable people associated with the Bateke

- Omar Bongo, President of Gabon

- Charles David Ganao (1928–2012), Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo (1996–1997)[2]

- Pascal Lissouba, president of the Republic of the Congo

- Ngalifourou (1864–1956), a queen of the Teke

Bateke dogs and cats

The Teke historically breed dogs and cats for domestic purposes. The chien Bateke is a small lean hunting dog with a short, medium gray coat. The chat Bateke is large cat with nearly the same coloring as the dog. These animals constitute landraces, rather than formal breeds (they are not recognized by any major fancier and breeder organizations). A majority of domesticated cats and dogs in areas bordering the Congo River are of these breeds, though ownership of domesticated animals in general is rare in the region.

See also

Notes

- Reed 1987, p. 287

- "Congo: décès de Charles Ganao, ancien Premier ministre de Lissouba". Jeuneafrique.com. 2012-07-06. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bateke. |

- Reed, Michael C. (June 1987), "Gabon: A Neo-Colonial Enclave of Enduring French Interest", The Journal of Modern African Studies, Cambridge University Press, 25 (2): 283–320, doi:10.1017/S0022278X00000392, JSTOR 161015, OCLC 77874468.