Basilica of San Magno, Legnano

The Basilica of Saint Magnus (it. Basilica di San Magno) is the principal church of the Italian town of Legnano, in the Province of Milan. It is dedicated to the Saint Magnus, who was Archbishop of Milan from 518 to 530. The church was built from 1504 to 1513 in the Renaissance-style designed by Donato Bramante. The bell tower was added between the years 1752 and 1791. On 18 March 1950, Pope Pious XII named the Basilica of San Magno a minor basilica.

| Basilica of San Magno | |

|---|---|

Basilica di San Magno | |

Basilica of San Magno from the Square. | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Province | Archdiocese of Milan |

| Rite | Ambrosian Rite |

| Location | |

| Location | Legnano, Italy |

Location in Italy | |

| Geographic coordinates | 45°35′41.64″N 8°55′9.12″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Donato Bramante |

| Style | Renaissance |

| Groundbreaking | May 4, 1504 |

| Completed | June 6, 1513 |

| Website | |

| www | |

The interior of the basilica church is adorned with numerous first-class examples of Lombard Renaissance artwork.[1] Examples are Gian Giacomo Lampugnani's frescoes of the main vault, the remains of 16th century paintings by Evangelista Luini, the frescoes of the main chapel by Bernardino Lanini, and the altarpiece by Giampietrino.[2] The item of greatest significance, however, is a polyptych by Bernardino Luini that is widely considered by art historians to be his masterpiece.[3][4]

History

The origins: the ancient church of San Salvatore

Upon the site of the Basilica of San Magno once stood the Lombard Romanesque parish church of San Salvatore, whose construction has been traced to the 10th or 11th centuries AD. By the 15th century, the stability of the parish church's foundation had been drastically weakened by its age and water leaking in from the nearby Olonella. To make matters worse, the Olona was prone to frequent and destructive flooding. Finally, in the very late 15th century, the parish church partially collapsed. The people of Legnano obtained permission from Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, to demolish its remains and to build a new church on the same site. Because the parish church had had a rather dour appearance, Legnano's populace decided to erect a much more sumptuous place of worship.[5]

There are a few reasons that the people chose, in spite of the danger of continued water damage, to reuse the site of the parish church. One is a confidence displayed by the people of Legnano in the technical skills of the builders of the basilica church.[6] Another is that what is now the Piazza San Magno was the town's primary cemetery until a fiat of the Napoleonic government forced the municipal government to move the cemetery out of the town in 1808.[7][8] The nobility were laid to rest inside the church until their bones were removed from the Basilica of San Magno in the 18th century.[9]

Construction

The greatest monetary contributions to the construction of the basilica church were made by the Lampugnani and Vismara families, two of the oldest families in Legnano.[10][11] The cornerstone was laid on 4 May 1504 and construction was finished on 6 June 1513. The decoration of the basilica church's interior began shortly thereafter with the frescoes of Gian Giacomo Lampugnani on the main dome. The church received its first two bells in 1510. The next year, however, on 11 December 1511, Legnano was razed and sacked Swiss soldiers, then fighting for the Holy League of 1511 during the War of the League of Cambrai. The church was also damaged; the scaffolding on its exterior was incinerated.[12][13] Writing about the construction of the basilica church, Agostino Pozzi, the provost of Legnano, reported in the Storia delle chiese di Legnano:[11]

[...] The church of S. Magno, as can be seen from a travel guide by Alessandro Lampugnano, was begun in 1504 on 4 May, and was built to perfection in 1513. And this building would have been built to perfection in a much shorter time, had it not been for the calamity of war that this country suffered, in particular the land of Legnano, given that, falling in the street of Varese in the year 1511 on 10 December, with one side bleached and the rest sacked; it confirms the work of Alessandro Lampugnano, and conforms to what Guicciardino says in his story in the book X. [...][lower-alpha 1]

— Agostino Pozzi, Storia delle chiese di Legnano, 1650

Work on the church was suspended from 1516 to 1523, for two reasons. The second was that funding for the church had ceased; the primary donors, the local nobility, were made destitute after the French drove the Sforzas from the Duchy of Milan in 1499 and subsequent fighting. That poverty among the nobility was also the author of much administrative disruption in Legnano, as they fought to hold onto their possessions within the Duchy. Compounding all these difficulties was a disinterest in Legnano by the Archbishop of Milan, who began withdrawing holy orders from the area. This had been provoked by the loss of the rebellious tendencies Seprio's inhabitants, and thus the need for ducal troops in Legnano.[14]

The original plans of the basilica have been lost and therefore no documents bearing the signature of its architect. Bramante's name, in fact, appears only in later written testimonies.[15] The design of the basilica of San Magno was probably carried out by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo or his follower Tommaso Rodari on a design by Donato Bramante.[10] The proof that assigns the authorship of the drawings to the famous artist is contained in a writing of 1650 by Agostino Pozzo, provost of San Magno, which reads:[16]

[...] The design of this building is by Bramante, architect of the most famous who had Christianity. [...][lower-alpha 2]

— Agostino Pozzi, Storia delle chiese di Legnano, 1650

The first document that mentions Donato Bramante as an architect of the basilica of San Magno is instead a text by Federico Borromeo, then archbishop of Milan, which is connected to his pastoral visit to Legnano in 1618, an excerpt of which states:[17]

[...] The architecture of this church is remarkable, which was entirely designed by the distinguished architect Bramante. This church needs an equally beautiful facade that aesthetically satisfies its view. It should therefore be made using precious marbles, providing niches, statues, pinnacles and other decorative elements, and everything necessary to increase its beauty. [...][lower-alpha 3]

— Excerpt from the document relating to the pastoral visit made in Legnano in 1618 by Cardinal Federico Borromeo

The construction was then directed by an unnamed master, and Legnano's most experienced artist, Gian Giacomo Lampugnani. Gian Giacomo was a distant relative of Oldrado II Lampugnani, the 13th century master builder who had built Lampugnani Manor and Visconteo Castle.[18] Gian Giacomo had also created the first piece of interior decor for the basilica with his 1515 fresco on the main vault.[6]

The basilica was consecrated on 15 December 1529 by Francesco Landino, auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of Milan.[11][19]

From 17th to 20th century

The entrance to the basilica, originally facing the Malinverni Palace and the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception was moved in 1610 to its present location. This entrance was walled off and transformed into an atrium to the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception.[20] The second original entrance, located in the Chapel of the Feast of the Cross, faced the clergy houses to the basilica's south. This entrance was also walled off,[21] and two new entrances opened on the front facade facing the Piazza San Magno.[22]

The main entrance was opened sometime before 1840, according to records from a pastoral visit by card. Giuseppe Pozzobonelli in 1761, as the side entrances did not allow visitors to enter directly before the high altar.[23] The work on the entrances was done by Francesco Maria Richini, a religious architect and the future designer of the Church of Madonnina dei Ronchi, also in Legnano.[24][25] He also modified the basilica's exterior by adding Baroque elements like pilasters, pediments, and lintels to the new entrances, windows, and roof lantern.[24] It is probable that the plans, were they not destroyed in 1515, were lost at this point.[14]

The basilica's north–south orientation was chosen because of urban planning; to its west was the old cemetery and on the east was the Olona, so it was decided that no doors should be placed on these sides of the basilica. The main chapel, however, was built facing east in traditional Christian practice. This resulted later in those entering the basilica from its new main entrance finding the high altar to their left, so the entrances were rotated 90° to the east and west. Another possibility is that, in the first half of the basilica's history, the high altar was aligned to the main entrance.[26]

On 20 August 1611, two bells that had been consecrated by Cardinal Federico Borromeo on 2 July 1610, were added to the bell tower.[19][22] One of these bells was cast with a fragment of a bell associated to a miracle performed by Saint Theodore acquired by the basilica's canon from the bishop of Sion, Switzerland, as recorded in the parish register.[19]

The modern main door was instead opened later, perhaps in 1840, or earlier, as shown by some archive notes relating to the pastoral visit made in Legnano by cardinal Giuseppe Pozzobonelli in 1761, in which there is a description of the Basilica of San Magno where the three doors facing the modern piazza San Magno are cited as well as drawn.[27] It was decided to open the central door because the two side entrances did not allow the visitor entering the basilica to be directly in front of the main altar.[21]

On 12 November 1850 a commission created by the Austrian government on the proposal of the provost of San Magno, and made up of the painters Francesco Hayez and Antonio de Antoni and the sculptor Giovanni Servi, wrote a report that had the purpose of carrying out a survey to evaluate the possibility of carry out a restoration of the basilica, a hypothesis which was not followed up.[14] In 1888 another restoration was organized, which however was not approved by the Conservation of Monuments for Lombardy.[28] The first restoration that went into port, made necessary to remedy the damage caused by a cyclone that struck Legnano on 20 July 1910, was then carried out from 1911 to 1914.[29]

The design by Donato Bramante is confirmed by the papal bull of March 19, 1950 issued by Pope Pius XII which conferred the dignity of a Roman minor basilica on the church of Legnano:[30][25]

[...] This temple, which dates back to the early 11th century, has been modified several times and finally rebuilt by the brilliant architect Donato Bramante, and constitutes a conspicuous ornament and decoration of the city. [...] We raise to the dignity and honor of Basilica Minor the church consecrated to God in the name of St. Magnus, in the city of Legnano, located in the territory of the Archdiocese of Milan, with the addition of all liturgical privileges, that for this reason they compete.[lower-alpha 4]

— Bull of Pope Pius XII of March 19, 1950, which elevated the church of San Magno to a Roman basilica

The title and the denomination

A hypothesis that explains the entitlement of the basilica to Magnus of Milan is linked to some events that took place a few decades after the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.[31] In 523 the Byzantine emperor Justin I promulgated an edict against the Arians: in response, the king of the Ostrogoths Theoderic the Great, who was of the Aryan faith, began to persecute Catholics, killing and imprisoning important religious figures as well. On the death of Theodoric, on the throne of the Ostrogoths, sat the most tolerant Athalaric: thanks to the new king, and to the intercession of Magno of Milan, the Milanese archbishop who was later proclaimed a saint, many prisoners were released.

Since these persecutions also affected Legnano, its inhabitants decided to name Magnus of Milan first the central apse of the ancient church of San Salvatore, then the parish, which was created on 24 December 1482 with the name of "parish of San Magno and San Salvatore",[30] and finally the new church: Magnus of Milan later became also the patron saint of the municipality of Legnano.

As far as the name is concerned, the legnanese basilica was originally known as "church of San Magno".[30] On 7 August 1584, on the occasion of the transfer of the provost tax from Parabiago to Legnano, change of location decreed by cardinal Carlo Borromeo, archbishop of Milan, the religious building changed its name to "provost church of San Magno" and the parish priest of Magnus of Milan acquired the title of provost.[30]

The transfer of the provost tax from Parabiago to Legnano (which also led to the creation of the parish church of the same name) was dictated by various reasons: from the greater number of inhabitants of the village of Legnano, to the fact that the church of San Magno was larger than the parabiaghese church of Santi Gervasio and Protasio, by the presence of the hospice of Sant'Erasmo and by the availability, in Legnano, of greater resources, also economic, as well as by the presence in the village of Milan of various ecclesiastical structures, including some convents.[30]

Faced with the displacement of the provost, the Parabiaghsis appealed to the pope, but without success, given the endorsement of the archiepiscopal decree by the Roman Curia, which occurred in 1586.[32] Officially acquired relevance also from the most important ecclesiastical hierarchies, from this century onwards, the legnanese church began to be called, to emphasize the relief, "collegiate church of San Magno".[30]

On March 19, 1950, with a papal bull, Pope Pius XII raised the provost church of San Magno to a Roman minor basilica, from which the modern name descended.[30]

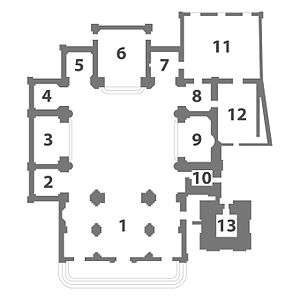

The plan of the basilica

|

Architecture

The church

The plan of the basilica is typically Renaissance. It no longer follows the typical elongated rectangular shape towards the altar of medieval churches, but has a central octagonal plan that allows a perspective view in all directions.[33] The visitor, in every position, can indeed find perspective angles, foreshortenings and architectural spaces that satisfy the view. In the Middle Ages, however, the perspective was all centered on the high altar.[33]

The Bramantesque churches do not have a main façade around which secondary volumes rotate, but they have a series of symmetries and perspective spaces that have about the same importance and form the whole of the entire structure.[33] The octagonal plan of the basilica of San Magno has a short transept that provides the church with a cross shape. On the corners of the latter there are also four small chapels.

The bell tower

The original bell tower that served the basilica was that of the ancient church of San Salvatore. Not having structural problems, he saved himself from demolition. This bell tower was extended in 1542, while in 1611 it was restructured and strengthened to allow the placement of the bells consecrated by Federico Borromeo, which were larger and heavier.[34] In 1638 another work of strengthening of the tower was carried out.[34] In the middle of the eighteenth century the ancient bell tower collapsed for two thirds, and then on December 2, 1752 work began on the construction of a new bell tower.[35]

As already mentioned, the remains of the old one were transformed into a chapel, which is still visible behind the bell tower of the Basilica of San Magno on the south side of the building, near a covered passage.[36] The design of the new bell tower was the work of Bartolomeo Gazzone. The new bell tower was built with a brick structure that replaced the one in stones of the previous bell tower. The height exceeds 40 meters.[34] Along the walls were provided with pilaster lesene.[34]

The parsonage

On the right side of the basilica there was, until 1967, an ancient 16th century clergy house.[37] This building was enlarged in the seventeenth century by order of Federico Borromeo, and again in the eighteenth century when the new bell tower was built. Already at the end of the nineteenth century part of the structure was demolished. The rest of the buildings, as already mentioned, were demolished in 1967 to allow the construction of the new parish center, which was inaugurated in 1972 by the Archbishop of Milan Giovanni Colombo.[29] The new rectory was manufactured in a modern style.

Artistic works

The facade and the entrance doors

Originally the facade and the other external walls of the basilica were not plastered and presented with exposed bricks. The appearance changed radically in 1914, when the graffiti plasters were made,[34] which covered the terracotta walls that had characterized the basilica for centuries, giving it an "unfinished" appearance: these works were carried out several centuries after construction of the church because the architect who designed it had left no drawings on possible decoration of the walls.[24]

The architects who followed him were therefore not sure about the type of coating to be applied to the walls of the basilica, since they did not know the idea that the original designer had.[24] To this was also added the desire to create high-quality plastering works that should have been up to the recognized architectural and artistic value of the basilica of Legnano: this indecision on the type of decoration to be applied led to the expansion of the times of their execution.

The three bronze entrance doors were built and then donated to the basilica on the occasion of the eighth centenary of the battle of Legnano (1176-1976) thanks to a popular subscription organized by the local Famiglia Legnanese Association, with the participation of the eight contrada that they take part annually in the city Palio di Legnano.[38] The depictions on the panels of the three doors are inspired by the battle of Legnano and the cultural traditions of the city.[38]

The doors were the work of the sculptor Franco Dotti and were blessed on May 30, 1976 by archbishop Giovanni Colombo before the traditional Mass on the copy of the Carroccio, an event that is part of the preparatory program for the historical parade, which ends at the stadio Giovanni Mari and which is followed by the horse race, an event that ends the event.[38] The blessing ceremony of the three doors was particularly solemn, also because it was included in the busy program of celebrations of the eighth centenary of the battle.[38]

The floor, the organ and the choir

The floor, which was made of white, black and red Verona marble, was laid in the 18th century.[39][40] It has a geometric checkered pattern made with inlay, with the motif under the dome that converges towards the center of the basilica, recalling the lines of the vault and - more generally - the curved profiles of the surrounding vertical walls, which in turn close together in the dome above.[39][14]

Until the 18th century the entire church was paved with terracotta tiles: this original flooring remained intact only in the chapel of sant'Agnese, which is therefore the only part of the basilica that was not paved with marble, while at the interior of the main chapel, during some works, the remains of the ancient terracotta flooring were found under the marble pavement.[40]

The choirs stalls, which are located inside the main chapel, were built in the 17th century in walnut wood by the Coiro brothers, or by the same carvers who carved the aforementioned small temple with a tabernacle in the sacristy.[40][41] The choir stalls, which are of fine artistic workmanship, have a Renaissance style.[40][42]

With the changes that took place in the first part of the 20th century, the ancient stalls of the choir of the basilica lost that austerity that was typical of the Renaissance period.[42] The platform built in the first part of the 20th century, however, concealed part of the frescoes on the walls, in particular the scenes of the Visit of the Magi and the Return of the family of Jesus to Nazareth, and therefore in 1968 a new platform was built, this time lower, which solved the problem.[42]

The organ of the basilica was built in 1542 by the Antegnati family[43] thanks to the testamentary bequest of Francesco Lampugnani, who donated 25 liras to the parish of San Magno for the realization of the musical instrument and 16 liras for its positioning.[30] The choir in walnut wood is instead the work of the painter Gersam Turri.[43] It was placed in its current position in 1640[22] and it was restored on two occasions (one in the 19th century and the other in the 20th century).

The organ of the basilica of San Magno, which is older than the one preserved in the Duomo of Milan, is perhaps the only pipe instrument manufactured by the Antegnati family that has come down to us practically intact.[44] According to many music experts, the organ of the basilica of San Magno is an excellent instrument, above all for the sweetness and sonority of the chords.[45]

The vault of the church

The first decorative work carried out in the basilica was carried out in 1515 by Gian Giacomo Lampugnani, who frescoed the grotesque church vault. Accompanied by the wise internal natural lighting originating from the side openings of the vault, which allow a calibrated luminosity at any time of day, the overall effect is of absolute importance,[39] so much so that even the art historian Eugène Müntz, who defined this decoration "the most beautiful grotesque in Lombardy".[18]

The vault is divided into eight segments within which the large candelabra are frescoed from which branches, starting from the bottom, are unwound.[6] Inside this drawing the windows of the dome open.[6] The painting is then completed with the representation of centaurs, dolphins, eagles, satyrs, sea horses, harpies, winged putti and dragons, whose dominant colors are white and gray in chiaroscuro.[6] The blue of the background was made using a lapis lazuli powder dye.[14]

Just below the dome there is an octagonal tholobate which is frescoed with a softer shade than that of the vault: this is the opposite of what is generally done in the decorations of contemporary churches in the basilica, which are instead characterized by stronger colors in the lower parts and more tenuous in the upper architectural sections.[46] The tholobate is characterized by the presence of twenty-four niches which are internally painted with a gray shade and with a rather dark blue color, which brings out the penumbra originating from the recesses: on the pillars of the drum are represented candelabras, which take up the decoration of the vault.[46]

In 1923 Gersam Turri painted in the spandrels, in the spaces between the major arches and in the capitals, twelve roundels, one in each architectural element, containing the faces as many biblical prophets (from left and right, starting from the arch located at the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament and of the outward, Joel, Daniel, Jonah, Obadiah, Amos, Haggai, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Ezekiel, Micah, Zechariah, and Malachi), which were added to the four prophets previously painted: Jeremiah and Isaiah, which are above the major chapel and which were presumably made by Bernardino Lanino; Solomon and David, painted by the Lampugnani brothers above the arch of the chapel of the Holy Crucifix.[14]

This cycle of paintings was made by Turri inspired by the frescoes in the main chapel, which are the work of Lanino.[3][46] The pilasters were decorated, again by Gersam Turri in 1923, with candelabra on a blue background: these decorations also resume the frescoing of the vault.[46] The sub-arches are embellished with paintings depicting the Greek.[46] The pilasters, before the frescoes by Gersam Turri, were all decorated with gray stripes and squares:[46] the same gray color was also characteristic of the spandrels then painted in 1923.[3]

The main chapel

The vault and walls of the main chapel were painted by Bernardino Lanino presumably between 1562 and 1564, at the height of his artistic maturity,[4] thanks to the economic contribution of the Lampugnani family.[26] The work of the Lanino consists of eight large frescoes plus two small scenes that are located above the windows: the cycle of paintings was designed to "rotate" around Bernardino Luini's polyptych, which is located in the center of the front wall and which it was created a few decades before this work.[3]

The cross vault is decorated with fruit festoons and pairs of cherubs, which were made with a grotesque style.[47] The dominant color of the vault is golden yellow, which deliberately contrasts with the dark blue of the main dome.[3] The subjects painted on the vault of the chapel have a typically 15th century Lombard style.[3] The upper part of the wall, being located under the cornice, is still, from an architectural point of view, part of the vault of the chapel; it is divided into lunettes, which are all frescoed.[47] The lateral lunettes, which are next to the large windows, depict the four evangelists: those on the left saint Matthew and saint John, while the lunettes on the right are saint Mark and saint Luke.[47] On the lunettes of the frontal wall instead the first four doctors of the Church, namely Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome and Pope Gregory I.[3][47]

The walls under the cornice were also painted.[47] On the wall to the right of the altar are represented the Marriage of the Virgin, the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Visit of the Magi.[48] The left wall is decorated with the Journey to Nazareth, the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Return to Nazareth and the Dispute.[49] In this last scene there are portraits of Lanino and his helper, who lend their faces to some passers-by[58]. The triumphal arch is instead frescoed with angels in flight and with geometric motifs decorated with fruits.[3] The lapel of the fresco that gives towards the center of the church is instead painted with candelabra of fruit and vegetables, while on the space between the triumphal arch and the pylons of the building there are two roundels that are supported by angels having the face of two prophets.[3]

On the back wall, on the sides of the Luini polyptych, are painted saint Roch and saint Sebastian, while on the entrance pillars are depicted Jesus Christ and saint Magnus. The latter are topped by canopies embellished with purple curtains.[48] Also frontally there are also depictions of the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah and four putti. This chapel, as a whole, has a great artistic value, especially with regard to the invoice of the painted characters.[48] According to experts, it represents one of Lanino's masterpieces.[48]

Behind the main altar is a polyptych by Bernardino Luini from 1523 depicting the Madonna and Child, seven musician angels and four saints (John the Baptist, saint Peter, Magnus and Ambrose).[50] This work is flanked by an God the Father depicted in a tympanum.[3] On the lower predella, inside the small vertical compartments, saint Luke and saint John, the Ecce homo, saint Matthew and saint Mark are depicted in dark light, while in the horizontal sections the Christ nailed is painted, again with the same technique the crucifixion of Jesus, the Pose in the Sepulcher, the Resurrection of Jesus and the supper at Emmaus.[41]

The side chapels

The chapel of Peter of Verona, located near the entrance, was frescoed in 1556 by Evangelista Luini, son of Bernardino.[3] They represented the martyrdom of saint Peter surrounded by God blessing (on the bezel) and some saints (on the pillars).[50][3] Later these paintings were lost and were rebuilt between the 19th and 20th centuries by Beniamino and Gersam Turri.[3]

The large side chapel on the left is dedicated to the Holy Crucifix. It was frescoed in 1925 with some depictions of biblical scenes.[51] The chapel contains a precious deposed wooden Christ, a crucifix and two papier-mâché statues depicting Our Lady of Sorrows and Mary Magdalene.[51] The frescoes are from 1925.[51] The chapel located on the opposite side, which is called dell'Assumption o dell'Immacolate, houses the aforementioned altarpiece by Giampietrino from 1490 and an 18th-century wooden statue of the Immaculate.[51] The frescoes are from the 17th century and depict the Assumption of Mary and some saints.[51]

The chapel of saint Charles and saint Magnus, which is the third on the left, was instead frescoed in 1924 with the representation of various figures of putti. It contains a relic of saint Magnus and two 17th century paintings depicting saint Charles Borromeo.[51] The stuccos are from the same period.[51] The chapel of the Andito, which is opposite, was not decorated by almost any painting to give an idea of how unadorned the basilica was before the realization of the pictorial works of the early 20th century.[51] The only fresco present is a 17th-century depiction of the Mary, mother of Jesus.[51]

The chapel of the Sacred Heart is instead on the left of the main altar. This chapel has frescoes from 1862 by Mosè Turri and decorations by the same painter that were executed in 1853. There is also a precious 17th century painting depicting the deposition of Christ, which is the work of Giovanni Battista Lampugnani. In the chapel there is also an ancient baptismal font in red marble of the mid-seventeenth century.[52]

The chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, which is dedicated to saint Peter and Paul the Apostle, is instead to the right of the main altar. There are frescoes from 1603 by Giovan Pietro Luini (known as "the Gnocco") depicting the angels and decorations of 1925 by Gersam Turri.[40] The chapel also contains a 17th-century painting by the Lampugnani brothers that depicts the crucifixion of Jesus and a painting of 1940 representing Thérèse of Lisieux.[40]

At the entrance, on the left, there is the chapel of saint Agnes. The two frescoes that decorate it are from the 16th century and are the work of Giangiacomo Lampugnani. One depicts the Madonna with the Child, saint Agnes, saint Ambrose, saint Magnus and saint Ursula, while the other represents the Nativity of Jesus. On the columns are instead depicted saint Jerome and Origen.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Magno (Legnano). |

- Magnus (bishop of Milan)

- Archdiocese of Milan

Notes

- [...] La chiesa di S. Magno, come si vede da un libro di maneggio fatto da un Alessandro Lampugnano, fu incominciata l'anno 1504 adì 4 maggio, et fu ridotta a perfettione l'anno 1513. Et questa fabrica sarebbe stata ridotta a perfettione in maggior brevità di tempo, se non fossero stati li disturbi di guerra che patì questo contorno, in particolare la terra di Legnano, atteso che, calando per la strada di Varese l'anno 1511 alli X dicembre, ne fu abbruggiata una parte e saccheggiato il resto; ne fa di ciò mentione il medemo tesoriere Alessandro Lampugnano, et è conforme a quello dice anco il Guicciardino nella sua storia nel libro X. [...][11]

- [...] Questa fabbrica è dissegno per quello si tiene Bramante architetto de' più famosi habbi hauto la cristianità [...][11]

- [...] È notevole l'architettura di questa chiesa, che è stata interamente progettata dall'insigne architetto Bramante. Questa chiesa necessita di una facciata altrettanto bella e che soddisfi esteticamente la sua vista. La si dovrà pertanto realizzare utilizzando marmi pregiati prevedendo nicchie, statue, pinnacoli e altri elementi decorativi, e tutto quanto necessario per aumentarne la bellezza [...]

- [...] Questo tempio, che risale agli inizi del XI secolo, più volte modificato e infine ricostruito dal geniale architetto Donato Bramante, costituisce un cospicuo ornamento e decoro della città. [...] Eleviamo alla dignità e all'onore di Basilica Minore la chiesa consacrata a Dio in nome di S. Magno, nella città di Legnano, posta nel territorio dell'Arcidiocesi milanese, con l'aggiunta di tutti i privilegi liturgici, che a tale titolo le competono. [...]

Citations

- Turri 1974, pp. 14, 18.

- Raimondi 1913, p. 78.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 252.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 116.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 206, 208, 210.

- Turri 1974, p. 21.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, pp. 256, 279.

- Raimondi 1913, p. 115.

- Parish of San Magno: Storia della parrocchia.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 245.

- Raimondi 1913, p. 76.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, pp. 248–9.

- Turri 1974, pp. 13, 16, 28.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 249.

- Turri 1974, p. 12.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 247.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 110.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 248.

- Turri 1974, p. 16.

- Turri 1974, p. 24.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 114.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 250.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, pp. 114–15.

- Turri 1974, p. 14.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 113.

- Turri 1974, p. 28.

- Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 115.

- Turri 1974, p. 17.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 251.

- "Storia parrocchia" (in Italian). parrocchiasanmagno.it. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 211.

- Raimondi 1913, p. 81.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 246.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 256.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, pp. 249-250.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 210.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, pp. 256-257.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 257.

- Turri 1974, p. 15.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 254.

- Turri 1974, p. 33.

- Turri 1974, p. 34.

- Turri 1974, p. 18.

- Turri 1974, p. 319.

- Turri 1974, p. 19.

- Turri 1974, p. 22.

- Turri 1974, p. 29.

- Turri 1974, p. 31.

- Turri 1974, pp. 30-31.

- "La basilica di San Magno: la storia" (in Italian). parrocchiasanmagno.it. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 253.

- D'Ilario et al. 1984, p. 253-254.

References

- D'Ilario, Giorgio; Gianazza, Egidio; Marinoni, Augusto; Turri, Marco (1984). Profilo storico della città di Legnano (in Italian). Edizioni Landoni. SBN IT\ICCU\RAV\0221175.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferrarini, Gabriella; Stadiotti, Marco (2001). Legnano. Una città, la sua storia, la sua anima (in Italian). Telesio editore. SBN IT\ICCU\RMR\0096536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raimondi, Giovanni Battista (1913). Legnano: il suo sviluppo, i suoi monumenti, le sue industrie (in Italian). Pianezza e Ferrari. SBN IT\ICCU\CUB\0533168.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turri, Marco (1974). La Basilica di San Magno a Legnano (in Italian). Istituto italiano d'arti grafiche. SBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0589368.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online references

- "Storia della parrocchia di San Magno" (in Italian). Parish of San Magno. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Magno (Legnano). |

- (in Italian) Website of the San Magno parish