Basilica di San Vincenzo

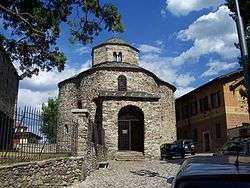

The Basilica di San Vincenzo is a church in Galliano, a frazione of Cantù, in Lombardy, northern Italy. An example of local Romanesque architecture, it was founded in 1007. The complex includes also a baptistry, dedicated to St. John the Baptist.

History

The church is located in Galliano, a small hamlet included within the comune of Cantù. The toponym derives from the ancient people of the Gallianates, whose name is mentioned in a Roman altar dedicated to Matronis Braecorium Gallianatium[1] Starting from the 2nd century, the worship of ancient gods such as Jupiter, Minerva and the Capitoline Triad was replaced by the Christian religion, in particular during the evangelization effort of Ambrose in the late 4th century. In the 5th century a Palaeo-Christian basilica, acting as the pieve of Cantù, existed in the site, perhaps with a baptstry. Of this structure, the black and white marble pavement remains in the current edifice's presbytery.

The current church was begun in the 10th century. The basilica was re-consecrated by Aribert, archbishop of Milan, who at the time was likely the hereditary tenant of the edifice: this is testified by the presence of graffitoes under the apse's frescoes, which mention the death of his father, brother and nephew.[1]

The church was nearly ruined at the time of archbishop Charles Borromeo (1560–1584). Later it was abandoned and used as peasants' store and lost the small right aisle in a fire. Other sections went lost during the French occupation in the early 19th century, when they were considered of no artistic interest and sold to private collectors. The basilica was acquired by the comune of Cantù in 1909 and restored in 1933–1934.

Description

The church has a simple and undecorated façade, in rough cobblestones. In the center is a portal with an architrave and an ogival lunette. The apse protrudes substantially from the main body. It features an archaic type of Lombard bands, with isolated arches characterized by pilasters that connect them to the ground. There are three windows which give light to the crypt: these are slightly different from those of the nave, due to the presence of a slight internal slope. The only remaining side apse is partly visible at the right.

The crypt, and subsequently the presbytery, are more elevated than in other Romanesque buildings. The crypt has two halls with cross vaults, above which, originally, were two ambons: today only part of the left one remains, with a marble eagle which once supported the lectern.

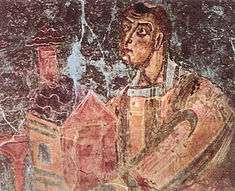

The church is known for the frescoes which cover the nave's walls and the apse. The latter are likely earlier than the former, as testified by the different style.[2] The apse frescoes show two bands of pictures with animals and vegetable motifs. They are surmounted by a praying Jesus within an almond frame. Jesus is wearing sandals, an uncommon feature of such depictions. He is flanked by two old men, the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel, behind whom are the two archangels Michael and Gabriel and two crowds. The lower walls of the apse show a short cycle of stories of St Vincent of Saragossa. The fourth panel features St Aribert offering a model of the church to God: the upper part of this scene is now at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana of Milan.

Next to the church is the contemporary Baptistry of St John, which was built at the same time. Its plan is inspired by that of the 9th century Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan, although in a simplified form: a cruciform shape with a square hall limited by four isolated columns and four perpendicular arches, and four semicircular niches. The western niche opens to the interior, from which stairs lead to the matronei (tribunes in the upper floor), which are not present in San Satiro. The interior ends with a dome, externally covered by an octagonal drum with four windows and small arches.

References

- Sannazaro, M. (1991). "Archeologia a san Vincenzo". Archeologia a Cantù. Como.

-

- Tamborini, Paola (1984). "Pittura d'età ottoniana e romanica. La Basilica di S. Vincenzo a Galliano". Storia di Monza e della Brianza. Milan.

Sources

- Tamborini, Paola (1984). "Pittura d'età ottoniana e romanica. La Basilica di S. Vincenzo a Galliano". Storia di Monza e della Brianza. Milan.