Bartolomeo Pinelli

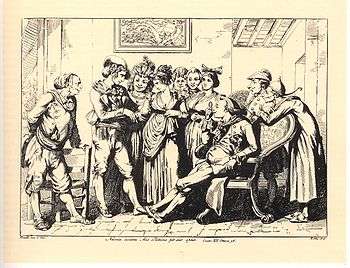

Bartolomeo Pinelli (November 20, 1781 – April 1, 1835) was an Italian illustrator and engraver.

Life

Pinelli was born and died in the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome, the son of an artisan who modeled religious statues.[1] Pinelli was educated first in Bologna and then at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. He return to live in Trastevere, then a poor quarter of Rome. His initial studio was on Piazza Sciarra on the Corso. His son, Achille Pinelli, was a famous watercolorist in his own right.

An extremely prolific engraver, his illustrations depicted the costumes of the Italian people, the great epic poems and numerous other subjects, including popular customs. In general, the most recurring subject is Rome, the ancient city as well as the modern one: its inhabitants and its monuments.[2]

In his first years of independent work, he painted figures in watercolor in the style of the painter Franz Kaiserman. Starting in 1807, he produced an album of 36 watercolors, entitled Scene e Costumi di Roma e del Lazio (Scenes and Costumes from Rome and the Lazio). His first series of engravings, begun in 1809, was entitled Raccolta di cinquanta costumi pittoreschi incisi all'acquaforte (Collection of 50 picturesque costumes engraved with acquaforte). In 1816 he finished the illustrations for his work La Storia Romana (Italian: Roman History) and, in 1821, those for the work La Storia Greca (Italian: Greek History). He held in high regard the traditions and religions of ancient Greece and Rome, and completed a series of engravings of the pantheon of classical gods.[3] The artistic tradition of exaltation of a class beyond the law finds roots in the baroque era artist Salvatore Rosa.

He also produced a series of prints on La Storia del Brigante Decapitito (Story of the Decapitated Brigand), about a brigand who, while he sleeps, is decapitated by his wife in revenge for having murdered her child. This particular work illustrates the attention Pinelli lavished on popular tales, and the idealized admiration that had developed among some of the educated and aristocratic class for brigand culture. Pinelli suggested that brigands or banditti in their quest for independence from the laws imposed by absolute rulers, an inheritance of the desire for liberty in ancient Republican Rome. For Pinelli, Italian nationalism would coalesce around a return to the values of Ancient Romans.[4] An example of the paradoxical patrons for his depictions of brigands are two paintings owned by the Duchess of Devonshire.[5]

Between 1822 and 1823 he finished a set of fifty-two prints for the a satiric poem called Il Meo Patacca.

He died poor on April 1, 1835.

Works

Oreste Raggi, writing in 1835, the same year that the artist died, cites many of Pinelli's designs and watercolors, and around forty collections of engravings published in Rome under ten different editors. Among those:

- Collection of Roman costumes (1809) – 50 copperplate engravings

- Another collection of Rome costumes – 50 copperplate engravings

- The carnival of Rome – one copperplate engraving

- Collection of Fifty Customs of the Neighbourhood of Rome, comprising diverse deeds of the Brigand[6]

- Roman History – 101 prints

- History of the emperors, starting from Ottavio – 101 prints

- Dante, Hell, Purgatory and Paradise – 145 prints

- Costumes of the Roman countryside (1823) – 50 copperplate engravings

- Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered – 72 prints

- Ariosto's Orlando Furioso – 100 prints

- Virgil's Aeneid – 50 copperplate engravings

- Collection of ancient costumes

- Greek History – 100 copperplate engravings

- Costumes of the Kingdom of Naples – 50 copperplate engravings (1828)

- Meo Patacca – 50 copperplate engravings

- Swiss costumes (1813) – 16 copperplate engravings

Frontispiece from Collection of 15 Swiss Costumes

Frontispiece from Collection of 15 Swiss Costumes

Bibliography

- Raggi, Oreste (1835). Cenni intorno alla vita e alle opere di Bartolomeo Pinelli (in Italian). Roma: Tipografia Salvucci.

- Fagiolo, Maurizio; Maurizio Marini (1983). Bartolomeo Pinelli (1781–1835) e il suo tempo (in Italian). Roma.

References

- Auber E. mentions the father as a door keeper.

- E. Deane in The Collector depicts a series of engravings of sites around Rome.

- Auber, Eugene. An Important Artistic Discovery, The Art Journal, Volume 56. London: The Art Union. p. 284.

- Crask, Matthew. Art in Europe 1700–1830. pp. 112–114.

- Deane, Ethel (1907). The Collector, containing articles and illustrations, reprinted from the Queen Newspaper..., Volume 3. London: Horace Cox. p. 299.

- The Penny Magazine for the Diffussion of Knowledge. London: Charles Knight and company. 1842. p. 20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bartolomeo Pinelli. |

- Works by Bartolomeo Pinelli at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bartolomeo Pinelli at Internet Archive

- Aneddoti su Pinelli by Giggi Zanazzo (in Romanesco)