Bankes's Horse

Marocco (c. 1586 – c. 1606), widely known as Bankes's Horse (after his trainer William Bankes), was the name of a late 16th- and early 17th-century English performing horse. He is sometimes referred to as the "Dancing Horse", the "Thinking Horse", or the "Politic Horse".

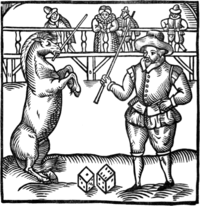

Marocco and William Bankes performing in an arena | |

| Species | Equus ferus caballus |

|---|---|

| Sex | Male |

| Born | c. 1586 Staffordshire, England |

| Died | c. 1606 (about 20) |

| Nation from | |

| Occupation | Performing horse |

| Owner | William Bankes |

Origin

William Bankes (also spelled Banks or Banckes, and sometimes called Richard Bankes) was born in Staffordshire, probably in the early 1560s,[1] In the 1580s he became a retainer of Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex;[2] his job may have been working in the stables.[1]

The horse that would be named Marocco was born around 1586; most sources agree he was bay, but some record him as white.[3][4] Soon thereafter he was obtained by Bankes,[1] who named him after the morocco leather from which contemporary saddles were made,[1] and jocularly addressed him as "seignior" (señor).[2] According to modern English physician and writer Jan Bondeson, "Marocco was a small, muscular horse with remarkable litheness and agility; he also proved particularly intelligent and easy to educate."[1]

London

Bankes sold his possessions and used the money to purchase silver horseshoes for Marocco, then moved to London to work at inn-yard theatres.[1] According to Thomas Nashe, Bankes had Marocco's tail bobbed: "Wiser was our Brother Bankes of these latter daies, who made his iugling horse a Cut, for feare if at anie time hee should foyst [defecate], the stinke sticking in his thicke bushie taile might be noysome to his Auditors."[5] Bankes lived at the Cross Keys Inn on Gracechurch Street, where their act performed.[1][2] A passage from Tarlton's Jests (1611) says:

The[re] was one Banks, in the time of Tarlton, who served the Erle of Essex, and had a horse of strange qualities, and being at the Crosse-keyes, in Gracious streete, getting mony with him, as he was mightily resorted to. Tarlton then, with his fellowes, playing at the Bel by, came into the Cross-keyes, amongst many people, to see fashions, which Banks perceiving, to make the people laugh, saies; seignior, to his horse, go fetch me the veryest foole in the company. The jade comes immediately, and with his mouth drawes Tarlton forth. Tarlton with merry words, said nothing but, "God a mercy, horse." In the end Tarlton, seeing the people laugh so, was angry inwardly, and said: Sir, had I power of your horse as you have, I would doe more than that. What ere it be, said Banks, to please him, I will charge him to do it. Then, said Tarleton: charge him bring me the veriest whore-master in the company. The horse leades his master to him. Then "God a mercy horse indeed," saies Tarlton, The people had much ado to keep peace; but Banks and Tarlton had like to have squar'd, and the horse by to give aime. But ever after it was a by word thorow London, God a mercy horse! and is so to this day.[2]

Exactly when Marocco and Bankes moved to London is unknown, but for Richard Tarlton (a renowned clown) to have seen the act, they must have arrived before Tarlton's death in September 1588. Bondeson has suggested that the entire episode with Tarlton was staged to garner publicity.[1]

Marocco could walk on two and three legs and play dead.[1] He could pull out particular audience members—such as people wearing spectacles—on Bankes's command;[1] he could distinguish between colors, such as green and violet (horses are only partially colorblind).[1][6] In one stunt, the horse drank a large bucket of water, then urinated on Bankes's command.[1] In another, he was told to pick out the "maids" (virgins) from the "maulkins" (harlots) in the audience.[1] When ordered to bow to the queen, Elizabeth I, Marocco was trained to do so; when ordered to bow to Philip II (King of Spain), the horse was trained to bare its teeth, whinny, and chase Bankes offstage.[1] This stunt was soon thereafter imitated by other animal trainers.[1] By 1593, John Donne had written:

But to a graue man, he doth moue no more

Than the wise politique horse would heretofore,

Or thou, O Elephant, or Ape, wilt doe,

When any names the k[ing] of Spaine to you.[7]

Whether by sleight-of-hand or by the horse's own talent, Marocco was known for his unusual counting abilities. Coins could be collected from the audience, and Marocco would indicate to whom each coin belonged and, with stomps of his hoof, how many coins had come from each.[1] Contemporary poet John Bastard wrote:

Bankes hath a horse of wondrous qualitie

For he can fight, and pisse, and daunce, and lie,

And finde your purse, and tell what coyne ye haue:

But Bankes, who taught your horse to smel a knaue?[8]

By the mid-1590s Marocco and Bankes had become some of London's most popular entertainers; Bankes was now wealthy, living and performing at the Bell Savage Inn, where Marocco was kept in the stables.[1] Eventually Bankes had an arena built on Gracechurch Street just for their act.[1] A musician was employed who played a song called "Bankes's Game" during the act, and who entertained the audience between shows. Although the tune and lyrics have not been preserved, the song "The Praise of a Pretty Lass; or, The Young Man's Dissimulation", published sometime in the early 17th century, follows the same tune.[9] The first verse goes:

Young men and maidens, to you Ile [I'll] declare,

I love my love, and she loveth me:

Yet to no goddesse will I her compare,

And yet she is pretty indifferent faire:

Will O, my love, O, there is none doth know

How I doe love thee.[9]

In addition, a ballad was published on 14 November 1595 by pamphleteer Edward White called "A ballad shewing the strange qualities of a yong nagg called Morocco", which is now lost.[1]

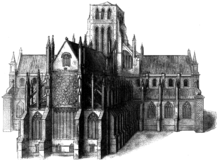

In 1601, perhaps to fight the growing competition of other animal trainers,[1] Bankes and Marocco ascended over a thousand steps to the rooftop of the then-flat St Paul's Cathedral and performed the act.[1] The show was a success, and even the clergy came out to watch the performance. Then, to the great astonishment of those watching, Marocco walked down the flight of stairs and out onto the street.[1] Writer Thomas Dekker wrote in The Guls Hornebooke (1609):

From hence you may descend to talke about the horse that went up, and striue if you can to know his keeper, take the day of the moneth, and the number of the steppes,—and suffer your selfe to beleeue verily that it was not a horse, but something else in the likeness of one.[10]

Travels and death

As the act's popularity grew, Bankes took it beyond London. Historian Patrick Henderson wrote in his History of Scotland (1596): "There came an Englishman to Edinburgh, with a chestain-coloured naig, which he called Marroco. […] He made him to do many rare and uncouth tricks, such as never horse was observed to do the like before in this land."[8] A journal entry from Shrewsbury in 1591 relates:

September 1591, 33 Eliz. This yeare and against the assise tyme on Master Banckes, a Staffordshire gentile, brought into this town of Salop a white horsse whiche wolld doe woonderfull and strange thinges, as thesse,—wold in a company or prese tell howe many peeces of money by hys foote were in a mans purce; also, yf the partie his master wolld name any man beinge hyd never so secret in the company, wold fatche hym owt with his mowthe, either naming hym the veriest knave in the company, or what cullerid coate he hadd; he pronowncid further to his horse and said, Sirha, there be two baylyves in the towne, the one of them bid mee welcom unto this towne and usid me in frindly maner; I wold have the goe to hym and gyve hym thanckes for mee; and he wold goe truly to the right baylyf that did so use hys sayd master as he did in the sight of a number of people, unto Master Baylyffe Sherar, and bowyd unto hym in makinge curchey withe hys foote in sutche maner as he coullde, withe suche strange feates for sutche a beast to doe, that many people judgid that it were impossible to be don except he had a famyliar or don by the arte of magicke.[4]

In March 1601, Bankes, Marocco, and their musician travelled to Paris and moved into the Lion d'Argent Inn on Rue Saint-Jacques.[1] Here Marocco became known as "Monsieur Moraco", and became immensely popular. A Parisian official finally arrested Bankes and charged him with sorcery, forcing Bankes to reveal that many of the tricks were accomplished through subtle hand gestures.[1]

Marocco, Bankes, and the musician moved on to Orléans, where their show was also met with success until Bankes was again arrested and sentenced to burn at the stake.[1] Bankes was given a last show to redeem himself, and during the performance Marocco knelt down before a cross held by one of the priests of the city, "proving" he was not of the devil.[1] When Bankes left Orléans, he was given "money and great commendations" for his troubles.[1]

Marocco's show continued to tour Europe, stopping in Frankfurt, Lisbon, Rome, and Wolfenbüttel as late as 1605.[1] Marocco probably died around 1606. After Marocco's death. Bankes revealed the secrets of his training to Gervase Markham, who published them in his book Cavelarice (1607).[1]

In 1608 Bankes was hired to work in James I's stables, and later trained horses for George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. He married and had a daughter, and was known for his wealth and wit in his old age.[1] Late in life he became a well known innkeeper, and died c. 1641.[1]

See also

Notes

- Bondeson, Jan (1999). "The Dancing Horse". The Feejee Mermaid and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History. United States: Cornell University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 0-8014-3609-5.

- Sharman, Julian (1546). The Proverbs of John Heywood. London: George Bell and Sons. pp. 134–135.

- Chambers, E. K. (1896). Poems of John Donne. London: Lawrence & Bullen. pp. 242–243.

- Halliwell-Phillipps, J. O. (1879). Memoranda on Love's Labour's Lost, King John, Othello, and on Romeo and Juliet. London: James Evan Adlard. pp. 70–73.

- Nashe, Thomas (1920). The Vnfortvnate Traveller: or, The Life of Jacke Wilton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 27.

- McDonnell, Sue (1 June 2007). "In Living Color". The Horse. The Horse, Inc. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- Jonson, Ben (1904). Bartholomew Fair. New York: Henry Holt and Co. p. 139.

- Notes and Queries: A Medium of Intercommunication for Literary Men, General Readers, etc. Vol. 167. London: John C. Francis. 1934. p. 40.

- Chappell, William (1874). The Roxburghe Ballads. Hertford: Steven Austin and Sons. pp. 284–289.

- Corser, Thomas (1860). "The Guls Hornebooke". Collectanea Anglo-poetica: or, A Bibliographical and Descriptive Catalogue of a Portion of a Collection of Early English Poetry, with Occasional Extracts and Remarks Biographical and Critical. Part 5. p. 165.

References

There is a full chapter about Bankes's Horse in Kevin De Ornellas, The Horse in Early Modern English Culture, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1611476583.

- Brewer, E. Cobham (1898) [1870]. "Banks's Horse". Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

- Corser, Thomas (1860). "Maroccus Extaticus: or, Bankes Bay Horse in a Trance". Collectanea Anglo-poetica: or, A Bibliographical and Descriptive Catalogue of a Portion of a Collection of Early English Poetry, with Occasional Extracts and Remarks Biographical and Critical. Part 1. pp. 152–156.

- Grose, Francis (1788). "Banks's Horse". A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. London.

- Howey, M. Oldfield (2002). "The Moral and Legal Responsibility of the Horse". The Horse in Magic and Myth. United States: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 215–219. ISBN 0-486-42117-1.

- Phipson, Emma (1883). "Marocco". The Animal-lore of Shakspeare's Time: Including Quadrupeds, Birds, Reptiles, Fish and Insects. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. pp. 109–111.

- Raleigh, Walter (1820) [1614]. "Of the divers kinds of unlawful Magic". A History of the World: In Five Books. Vo. 1. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable & Co. pp. 170.

- Russell, Constance; others (1904). "The Thinking Horse". Notes and Queries: A Medium of Intercommunication for Literary Men, General Readers, etc. Vol. 10:2. London: John C. Francis. pp. 165–166, 281–292.

- Smollett, Tobias George (1779). The Critical Review: or, Annals of Literature. Vol. 47. London: W. Simpkin and R. Marshall. pp. 134–135.