Ballaios

Ballaios (Ancient Greek: Βαλλαῖος; Latin: Ballaeus; ruled c. 167 – c. 135 BC or c. 195 – c. 175 BC) was an Illyrian king of the Ardiaei. Ballaios was not mentioned by any ancient writers. Ballaios is considered to have been a powerful and influential king as testified by the abundance of his silver and bronze coinage found along both coasts of the Adriatic.[1]

| Ballaios | |

|---|---|

Bronze coin of Ballaios. | |

| Reign | 167–135 BC |

| Predecessor | Gentius (probable) |

| Ancient Greek | Βαλλαῖος |

His silver issues are rare, but bronze coins[2] (without the royal title) occur on Hvar, both in single finds and in hoards, and at Rhizon in a different series bearing the royal title. The coins of Ballaios were widely imitated in the region, sometimes so crudely that they are unintelligible.

Ballaios reigned from his capital at Rhizon, a strong and well fortified city. The dating of his reign has been much disputed but he seems to have ruled after the defeat of Gentius in 168 BC by the Romans.[1][3]

Identification

Ballaios was not[1] mentioned by any ancient writers, of his time or those of later eras. Ballaois was a king attested on coins found on both coasts of the Adriatic. Hence had he been documented by Polybius or Livy, he would have no doubt been called an 'Illyrian king'. He is currently interpreted as an Illyrian ruler documented solely on his coins. Whilst the abundance of his coinage in the region would suggest that he was a very influential figure there is no literary or historical evidence of his existence.[4] The coins of the well-known Illyrian king Gentius are scarce in comparison to the coins of Ballaios. Ballaios appears to have ruled at Queen Teuta's old stronghold, Rhizon (now Risan). At the time the region was part of the Roman republic and the Ardiaean State had been dissolved since the time of Gentius.

According to the opinion of the majority of modern scholars, he inherited the Ardiaean State of Gentius after 168 BC.[5] Ballaios might have been involved in the Roman campaign against the Delmatae in 156 BC, and even taken part in the wars.[6] Ballaios seems to have had a conflict with Pharos or an Illyrian dynast after 168 BC.[7] Such assumptions seemed to some scholars to find confirmation in Livy's narrative concerning the Third Illyrian War. Livy mentions that after his defeat, Gentius sent two envoys from among the prominent tribal leaders as ambassadors to Rome to negotiate with the Roman L. Anicius.[8] The names of these ambassadors were Teuticus and Bellus, and the historian Hasan Ceka hypothesized that the name of Bellus might have been an incorrect transcription for Ballaios.[9] Ceka's proposal was accepted by many historians, although from the linguistic point of view this identification is very problematic. The argument would not carry much weight even if the envoy was called Ballaios. The Romans annihilated the Ardiaean State and founded three administrative regions in which there was no place for a king, so an envoy could not have inherited the throne.[10]

According to the proposal put forward by Giovanni Gorini, Ballaios would have reigned from 195 BC to 175 BC. No descendants or successors of Pinnes are known from historical sources. Ballaios could in theory have been an immediate successor of Pinnes, but in any case he was the king of the Ardiaean State. It is impossible to know exactly when Ballaios began to reign. according to the numismatic evidence some time around the start of the century, but most probably he was a contemporary of either Pleuratus III or Gentius. Weighty arguments speak against the thesis that he would have reigned after 168 BC and the division of Illyria into three parts, as his reign has been traditionally dated.[11] Also Ballaios must have died at least some time before the fall of Gentius, since Gentius was in possession of Rhizon before his defeat. The inhabitants of Rhizon were awarded immunity by the Romans because they had abandoned Gentius While he was still in power.[12] Why Ballaios was not mentioned in historical sources could be explained by the fact that his political importance and influence could not match that of Pleuratus III or Gentius. Gentius and Ballaios had two different centres of power. After the defeat of the Ardiaean State in 168 BC, there would have been no place for a king or even a local ruler.[13]

Coinage

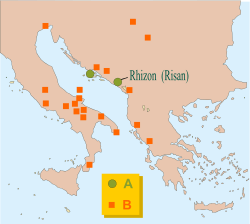

Ballaios minted coins in his own name. His coins with the long legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΛΛΑΙΟΥ (βασιλέως Βαλλαίου) were minted in Rhizon while the coins with the short legend ΒΑΛΛΑΙΟΥ and the head of the king Ballaios which is of a different type and are older, were minted in Pharos. In some cases it is possible to observe that Ballaios' coins were over struck on the older Pharos specimens. The distribution of his coinage indicates that they were concentrated in the central Dalmatian area, while a large number of different dies that could have been identified to date indicates a long minting of his coins. Numismatic evidence shows that Ballaios reigned for quite a lengthy time. His coins are also frequently found in Italy, which confirms the trade contacts between both Adriatic coasts.

On the obverse of the coins a bust of the king facing left to right is depicted, while on the reverse Artemis, advancing or standing, is represented with or without a torch, sometimes carrying one or two spears, surrounded by either the long or short legend.[14] Most of these coins are bronze, some, and always those with the long legend are silver. Their weight, c. 3.5g corresponds top the Roman victorium. It is significant the Ballaios also had silver coins minted, which indicates his wealth and power, since elsewhere in Hellenistic Dalmatia silver coinage is very rarely documented from Greek/Illyrian mints. The weight of the bronze coins of Ballaios is between 1.0 and 4.5g, while most of the documented specimens weigh between 2.0 and 2.5g. The relatively great impact of the coinage of Ballaios is also indicated by a large number of imitations of his coins.[15] In several instances on some coins, an embossed circular Illyrian shield on one side and the flying horse Pegasus, a mythological creature, and the letter "B", "A" and "L" on the other side, are depicted.

Ballaios' coins were in circulation in the regions along both Adriatic coasts; along the eastern Adriatic, they have been found in a broad area extending from Phoenice in Epirus to Shkodër, in present-day Albania, to Pharos, and along the western Adriatic from Leuca and Locri to Aquileia, indicating trade activity of Ballaios that was no longer controlled by Issa.[16] As expected the coins of Ballaios were also found in the broad area of Narona, the most important Greek/Illyrian emporium which maintained along with the river Neretva, commercial and other contacts with the interior regions or Illyricum.

The first to divide the coins of Ballaios into two groups was Arthur J. Evans, who distinguished the Rhizon group and the Pharos group, and dated both in the period between 167 BC and 135 BC. Josip Brunsmid was the next to discuss the coins of Ballaios. He agreed with Evans on the late chronology of the coins, postulating that Ballaios had possessed a part of the island of Pharos with a mint. He thus doubted that Rhizon then in Roman possession could have been a royal residence and a mint.[17] Ivan Marovic, who maintained that both types had been struck on Pharos, proposed a different division of Ballaios' coins than that of Evans. He distinguished two groups of each of the two types with and without the legal title, a group with the head of Ballaios to the right and a group with the head to the left, giving precedence to the obverse rather than the reverse. However, later excavation at Rhizon, have uncovered new coins of Ballaios, which confirmed the hypothesis that of a mint having been located in Rhizon. In June 2010 at the site of the customs house in Rhizon, 4600 coins of king Ballaios were discovered, placed in a bowl-like pot.[18]

Gorini supposed, on the basis of a few silver coins that were found in Rhizon which bear the long legend with the regal title, that Rhizon had been the capital of Ballaios' state. On those coins, Artemis is depicted as advancing to the left, and is similar to the goddess depicted on Acarnanian coins dated to around 200 BC.[19] Ballaios may have well begun to mint his coins based on Acarnanian coinage designs. Political and economic relations between Illyrian monarchs and various Greek regions, as well as even marriage ties between Illyrian and Greek kings and queens were hardly exceptional. The finding of Ballaios coins along with other Illyrian and Greeks coins in Bari in southern Italy has made Gorini date the deposition of the hoard, which may have been a votive offering, to c.125 BC.[20] Other sites where the coinage of Ballaios has been found in an archaeological context is in the city of Daorson.

See also

- Illyrian coinage

- Illyrian warfare

- List of rulers of Illyria

References

- Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: mélanges offerts au professeur Pierre Cabanes by Danièle Berranger, Pierre Cabanes, Danièle Berranger-Auserve, page 137

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, page 179

- Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: mélanges offerts au professeur Pierre Cabanes by Danièle Berranger, Pierre Cabanes, Danièle Berranger-Auserve, page 145

- Illyrian Coins

- Peter Kos 1997 p.44–45

- Pierre Cabanes 1988 p.325

- Arthur M. Eckstein 1999 p.416

- Livy (44.31.9)

- Hasan Ceka 1988 8.ff

- Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: mélanges offerts au professeur Pierre Cabanes page@127

- Duje Rendic-Miocevic 1972–1973, p.260–4

- Livy (45.26.13)

- Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: mélanges offerts au professeur Pierre Cabanes p137

- Arthur J. Evans 1880 p.296–8

- Giovanni Gorini "Re Ballaois"

- Paolo Visona - Paris 1993 page 252

- Josip Brunsmid 1898 p.76–85

- Radio Kotor, 10.6.2010 Otkriven novac kralja Balajosa Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Giovanni Gorini "Re Ballaios" p.48

- Giovanni Gorini 1999 p.99–105

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illyria & Illyrians. |