Ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French chanson balladée or ballade, which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Britain and Ireland from the later medieval period until the 19th century. They were widely used across Europe, and later in Australia, North Africa, North America and South America. Ballads are often 13 lines with an ABABBCBC form, consisting of couplets (two lines) of rhymed verse, each of 14 syllables. Another common form is ABAB or ABCB repeated, in alternating 8 and 6 syllable lines.

Many ballads were written and sold as single sheet broadsides. The form was often used by poets and composers from the 18th century onwards to produce lyrical ballads. In the later 19th century, the term took on the meaning of a slow form of popular love song and is often used for any love song, particularly the sentimental ballad of pop or rock music, although the term is also associated with the concept of a stylized storytelling song or poem, particularly when used as a title for other media such as a film.

Origins

The ballad derives its name from medieval Scottish dance songs or "ballares" (L: ballare, to dance),[1] from which 'ballet' is also derived, as did the alternative rival form that became the French ballade.[2][3] As a narrative song, their theme and function may originate from Scandinavian and Germanic traditions of storytelling that can be seen in poems such as Beowulf.[4] Musically they were influenced by the Minnelieder of the Minnesang tradition.[5] The earliest example of a recognizable ballad in form in England is "Judas" in a 13th-century manuscript.[6]

Ballad form

Ballads were originally written to accompany dances, and so were composed in couplets with refrains in alternate lines. These refrains would have been sung by the dancers in time with the dance.[7] Most northern and west European ballads are written in ballad stanzas or quatrains (four-line stanzas) of alternating lines of iambic (an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable) tetrameter (eight syllables) and iambic trimeter (six syllables), known as ballad meter. Usually, only the second and fourth line of a quatrain are rhymed (in the scheme a, b, c, b), which has been taken to suggest that, originally, ballads consisted of couplets (two lines) of rhymed verse, each of 14 syllables.[8] This can be seen in this stanza from "Lord Thomas and Fair Annet":

The horse | fair Ann | et rode | upon |

He amb | led like | the wind |,

With sil | ver he | was shod | before,

With burn | ing gold | behind |.[4]

There is considerable variation on this pattern in almost every respect, including length, number of lines and rhyming scheme, making the strict definition of a ballad extremely difficult. In southern and eastern Europe, and in countries that derive their tradition from them, ballad structure differs significantly, like Spanish romanceros, which are octosyllabic and use consonance rather than rhyme.[9]

Ballads usually are heavily influenced by the regions in which they originate and use the common dialect of the people. Scotland's ballads in particular, both in theme and language, are strongly characterised by their distinctive tradition, even exhibiting some pre-Christian influences in the inclusion of supernatural elements such as travel to the Fairy Kingdom in the Scots ballad "Tam Lin".[10] The ballads do not have any known author or correct version; instead, having been passed down mainly by oral tradition since the Middle Ages, there are many variations of each. The ballads remained an oral tradition until the increased interest in folk songs in the 18th century led collectors such as Bishop Thomas Percy (1729–1811) to publish volumes of popular ballads.[7]

In all traditions most ballads are narrative in nature, with a self-contained story, often concise, and rely on imagery, rather than description, which can be tragic, historical, romantic or comic.[8] Themes concerning rural laborers and their sexuality are common, and there are many ballads based on the Robin Hood legend.[11] Another common feature of ballads is repetition, sometimes of fourth lines in succeeding stanzas, as a refrain, sometimes of third and fourth lines of a stanza and sometimes of entire stanzas.[4]

Composition

Scholars of ballads have been divided into "communalists", such as Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) and the Brothers Grimm, who argue that ballads are originally communal compositions, and "individualists" such as Cecil Sharp, who assert that there was one single original author.[6] Communalists tend to see more recent, particularly printed, broadside ballads of known authorship as a debased form of the genre, while individualists see variants as corruptions of an original text.[12] More recently scholars have pointed to the interchange of oral and written forms of the ballad.[13]

Transmission

The transmission of ballads comprises a key stage in their re-composition. In romantic terms this process is often dramatized as a narrative of degeneration away from the pure 'folk memory' or 'immemorial tradition'.[14] In the introduction to Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802) the romantic poet and historical novelist Walter Scott argued a need to 'remove obvious corruptions' in order to attempt to restore a supposed original. For Scott, the process of multiple recitations 'incurs the risk of impertinent interpolations from the conceit of one rehearser, unintelligible blunders from the stupidity of another, and omissions equally to be regretted, from the want of memory of a third.' Similarly, John Robert Moore noted 'a natural tendency to oblivescence'.[15]

Classification

European Ballads have been generally classified into three major groups: traditional, broadside and literary. In America a distinction is drawn between ballads that are versions of European, particularly British and Irish songs, and 'Native American ballads', developed without reference to earlier songs. A further development was the evolution of the blues ballad, which mixed the genre with Afro-American music. For the late 19th century the music publishing industry found a market for what are often termed sentimental ballads, and these are the origin of the modern use of the term 'ballad' to mean a slow love song.

Traditional ballads

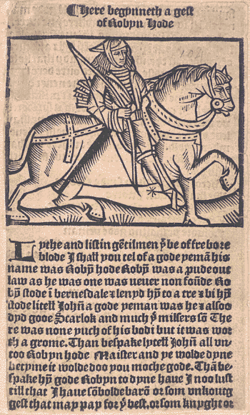

The traditional, classical or popular (meaning of the people) ballad has been seen as beginning with the wandering minstrels of late medieval Europe.[4] From the end of the 15th century there are printed ballads that suggest a rich tradition of popular music. A reference in William Langland's Piers Plowman indicates that ballads about Robin Hood were being sung from at least the late 14th century and the oldest detailed material is Wynkyn de Worde's collection of Robin Hood ballads printed about 1495.[16]

Early collections of English ballads were made by Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) and in the Roxburghe Ballads collected by Robert Harley, (1661–1724), which paralleled the work in Scotland by Walter Scott and Robert Burns.[16] Inspired by his reading as a teenager of Reliques of Ancient English Poetry by Thomas Percy, Scott began collecting ballads while he attended Edinburgh University in the 1790s. He published his research from 1802 to 1803 in a three-volume work, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. Burns collaborated with James Johnson on the multi-volume Scots Musical Museum, a miscellany of folk songs and poetry with original work by Burns. Around the same time, he worked with George Thompson on A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice.[17]

Both Northern English and Southern Scots shared in the identified tradition of Border ballads, particularly evinced by the cross-border narrative in versions of "The Ballad of Chevy Chase" sometimes associated with the Lancashire-born sixteenth-century minstrel Richard Sheale.[18]

It has been suggested that the increasing interest in traditional popular ballads during the eighteenth century was prompted by social issues such as the enclosure movement as many of the ballads deal with themes concerning rural laborers.[19] James Davey has suggested that the common themes of sailing and naval battles may also have prompted the use (at least in England) of popular ballads as naval recruitment tools.[20]

Key work on the traditional ballad was undertaken in the late 19th century in Denmark by Svend Grundtvig and for England and Scotland by the Harvard professor Francis James Child.[6] They attempted to record and classify all the known ballads and variants in their chosen regions. Since Child died before writing a commentary on his work it is uncertain exactly how and why he differentiated the 305 ballads printed that would be published as The English and Scottish Popular Ballads.[21] There have been many different and contradictory attempts to classify traditional ballads by theme, but commonly identified types are the religious, supernatural, tragic, love ballads, historic, legendary and humorous.[4] The traditional form and content of the ballad were modified to form the basis for twenty-three bawdy pornographic ballads that appeared in the underground Victorian magazine The Pearl, which ran for eighteen issues between 1879 and 1880. Unlike the traditional ballad, these obscene ballads aggressively mocked sentimental nostalgia and local lore.[22]

Broadsides

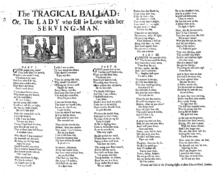

Broadside ballads (also known as 'broadsheet', 'stall', 'vulgar' or 'come all ye' ballads) were a product of the development of cheap print in the 16th century. They were generally printed on one side of a medium to large sheet of poor quality paper. In the first half of the 17th century, they were printed in black-letter or gothic type and included multiple, eye-catching illustrations, a popular tune title, as well as an alluring poem.[23] By the 18th century, they were printed in white letter or roman type and often without much decoration (as well as tune title). These later sheets could include many individual songs, which would be cut apart and sold individually as "slip songs." Alternatively, they might be folded to make small cheap books or "chapbooks" which often drew on ballad stories.[24] They were produced in huge numbers, with over 400,000 being sold in England annually by the 1660s.[25] Tessa Watt estimates the number of copies sold may have been in the millions.[26] Many were sold by travelling chapmen in city streets or at fairs.[27] The subject matter varied from what has been defined as the traditional ballad, although many traditional ballads were printed as broadsides. Among the topics were love, marriage, religion, drinking-songs, legends, and early journalism, which included disasters, political events and signs, wonders and prodigies.[28]

Literary ballads

Literary or lyrical ballads grew out of an increasing interest in the ballad form among social elites and intellectuals, particularly in the Romantic movement from the later 18th century. Respected literary figures Robert Burns and Walter Scott in Scotland collected and wrote their own ballads. Similarly in England William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge produced a collection of Lyrical Ballads in 1798 that included Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Keats were attracted to the simple and natural style of these folk ballads and tried to imitate it.[29] At the same time in Germany Goethe cooperated with Schiller on a series of ballads, some of which were later set to music by Schubert.[30] Later important examples of the poetic form included Rudyard Kipling's "Barrack-Room Ballads" (1892-6) and Oscar Wilde's The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1897).[31]

Ballad operas

In the 18th century ballad operas developed as a form of English stage entertainment, partly in opposition to the Italian domination of the London operatic scene.[32] It consisted of racy and often satirical spoken (English) dialogue, interspersed with songs that are deliberately kept very short to minimize disruptions to the flow of the story. Rather than the more aristocratic themes and music of the Italian opera, the ballad operas were set to the music of popular folk songs and dealt with lower-class characters.[33] Subject matter involved the lower, often criminal, orders, and typically showed a suspension (or inversion) of the high moral values of the Italian opera of the period.

The first, most important and successful was The Beggar's Opera of 1728, with a libretto by John Gay and music arranged by John Christopher Pepusch, both of whom probably influenced by Parisian vaudeville and the burlesques and musical plays of Thomas d'Urfey (1653–1723), a number of whose collected ballads they used in their work.[34] Gay produced further works in this style, including a sequel under the title Polly. Henry Fielding, Colley Cibber, Arne, Dibdin, Arnold, Shield, Jackson of Exeter, Hook and many others produced ballad operas that enjoyed great popularity.[35] Ballad opera was attempted in America and Prussia. Later it moved into a more pastoral form, like Isaac Bickerstaffe's Love in a Village (1763) and Shield's Rosina (1781), using more original music that imitated, rather than reproduced, existing ballads. Although the form declined in popularity towards the end of the 18th century its influence can be seen in light operas like that of Gilbert and Sullivan's early works like The Sorcerer as well as in the modern musical.[36]

In the 20th century, one of the most influential plays, Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht's (1928) The Threepenny Opera was a reworking of The Beggar's Opera, setting a similar story with the same characters, and containing much of the same satirical bite, but only using one tune from the original.[37] The term ballad opera has also been used to describe musicals using folk music, such as The Martins and the Coys in 1944, and Peter Bellamy's The Transports in 1977.[38] The satiric elements of ballad opera can be seen in some modern musicals such as Chicago and Cabaret.[39]

Beyond Europe

American ballads

Some 300 ballads sung in North America have been identified as having origins in British traditional or broadside ballads.[40] Examples include 'The Streets of Laredo', which was found in Britain and Ireland as 'The Unfortunate Rake'; however, a further 400 have been identified as originating in America, including among the best known, 'The Ballad of Davy Crockett' and 'Jesse James'.[40] They became an increasing area of interest for scholars in the 19th century and most were recorded or catalogued by George Malcolm Laws, although some have since been found to have British origins and additional songs have since been collected.[40] They are usually considered closest in form to British broadside ballads and in terms of style are largely indistinguishable, however, they demonstrate a particular concern with occupations, journalistic style and often lack the ribaldry of British broadside ballads.[13]

Blues ballads

The blues ballad has been seen as a fusion of Anglo-American and Afro-American styles of music from the 19th century. Blues ballads tend to deal with active protagonists, often anti-heroes, resisting adversity and authority, but frequently lacking a strong narrative and emphasising character instead.[40] They were often accompanied by banjo and guitar which followed the blues musical format.[13] The most famous blues ballads include those about John Henry and Casey Jones.[40]

Bush ballads

The ballad was taken to Australia by early settlers from Britain and Ireland and gained particular foothold in the rural outback. The rhyming songs, poems and tales written in the form of ballads often relate to the itinerant and rebellious spirit of Australia in The Bush, and the authors and performers are often referred to as bush bards.[41] The 19th century was the golden age of bush ballads. Several collectors have catalogued the songs including John Meredith whose recording in the 1950s became the basis of the collection in the National Library of Australia.[41] The songs tell personal stories of life in the wide open country of Australia. Typical subjects include mining, raising and droving cattle, sheep shearing, wanderings, war stories, the 1891 Australian shearers' strike, class conflicts between the landless working class and the squatters (landowners), and outlaws such as Ned Kelly, as well as love interests and more modern fare such as trucking.[42] The most famous bush ballad is "Waltzing Matilda", which has been called "the unofficial national anthem of Australia".[43]

Sentimental ballads

Sentimental ballads, sometimes called "tear-jerkers" or "drawing-room ballads" owing to their popularity with the middle classes, had their origins in the early "Tin Pan Alley" music industry of the later 19th century. They were generally sentimental, narrative, strophic songs published separately or as part of an opera (descendants perhaps of broadside ballads, but with printed music, and usually newly composed). Such songs include "Little Rosewood Casket" (1870), "After the Ball" (1892) and "Danny Boy".[40] The association with sentimentality led to the term "ballad" being used for slow love songs from the 1950s onwards. Modern variations include "jazz ballads", "pop ballads", ""rock ballads", "R&B ballads" and "power ballads".[44]

See also

- Corrido and Narcocorrido

- Graves, Alfred Perceval

- List of the Child Ballads

- List of folk song collections

- List of Irish ballads

- List of rock ballads

- Murder ballad

- Roud Folk Song Index

- Song structure (popular music)

- Torch song

- Vaar

Notes

- W. Apel, Harvard Dictionary of Music (Harvard, 1944; 2nd edn., 1972), p. 70.

- A. Jacobs, A Short History of Western Music (1972, Penguin, 1976), p. 21.

- W. Apel, Harvard Dictionary of Music (1944, Harvard, 1972), pp. 70-72.

- J. E. Housman, British Popular Ballads (1952, London: Ayer Publishing, 1969), p. 15.

- A. Jacobs, A Short History of Western Music (Penguin 1972, 1976), p. 20.

- A. N. Bold, The Ballad (Routledge, 1979), p. 5.

- "Popular Ballads", The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century, p. 610.

- D. Head and I. Ousby, The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 66.

- T. A. Green, Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art (ABC-CLIO, 1997), p. 81.

- "Popular Ballads" The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century, pp. 610-17.

- "Songs of Protest, Songs of Love: Popular Ballads in Eighteenth-Century Britain | Reviews in History". www.history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- M. Hawkins-Dady, Reader's Guide to Literature in English (Taylor & Francis, 1996), p. 54.

- T. A. Green, Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art (ABC-CLIO, 1997), p. 353.

- Ruth Finnegan, Oral Poetry: Its Nature, Significance and Social Context (Cambridge University Press, 1977), p. 140.

- "The Influence of transmission on the English Ballads", Modern Language Review 11 (1916), p. 387.

- B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 45.

- Gregory, E. David (April 13, 2006). Victorian Songhunters: The Recovery and Editing of English Vernacular Ballads and Folk Lyrics, 1820-1883. Scarecrow Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-4616-7417-7. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- D. Gregory, '"The Songs of the People for Me": The Victorian Rediscovery of Lancashire Vernacular Song', Canadian Folk Music/Musique folklorique canadienne, 40 (2006), pp. 12-21.

- Robin Ganev,Songs of Protest, Songs of Love: Popular Ballads in 18th Century Britain

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2012-08-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- T. A. Green, Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art (ABC-CLIO, 1997), p. 352.

- Thomas J. Joudrey, "Against Communal Nostalgia: Reconstructing Sociality in the Pornographic Ballad," Victorian Poetry 54.4 (2017).

- E. Nebeker, "The Heyday of the Broadside Ballad", English Broadside Ballad Archive, University of California-Santa Barbara, retrieved 15 August 2011.

- G. Newman and L. E. Brown, Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714–1837: An Encyclopedia (Taylor & Francis, 1997), pp. 39-40.

- B. Capp, 'Popular literature', in B. Reay, ed., Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England (Routledge, 1985), p. 199.

- T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 11.

- M. Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and Its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 111-28.

- B. Capp, 'Popular literature', in B. Reay, ed., Popular Culture in Seventeenth-Century England (Routledge, 1985), p. 204.

- "Popular Ballads", The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, p. 610.

- J. R. Williams, The Life of Goethe (Blackwell Publishing, 2001), pp. 106-8.

- S. Ledger, S. McCracken, Cultural Politics at the Fin de Siècle (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 152.

- M. Lubbock, The Complete Book of Light Opera (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962) pp. 467-68.

- "Ballad opera", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 7 April 2015.

- F. Kidson, The Beggar's Opera: Its Predecessors and Successors (Cambridge University Press, 1969), p. 71.

- M. Lubbock, The Complete Book of Light Opera (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962), pp. 467-68.

- G. Wren, A Most Ingenious Paradox: The Art of Gilbert and Sullivan (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 41.

- K. Lawrence, Decolonizing Tradition: New Views of Twentieth-century "British" Literary Canons (University of Illinois Press, 1992), p. 30.

- A. J. Aby and P. Gruchow, The North Star State: A Minnesota History Reader, (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002), p. 461.

- L. Lehrman, Marc Blitzstein: A Bio-bibliography (Greenwood, 2005), p. 568.

- N. Cohen, Folk Music: a Regional Exploration (Greenwood, 2005), pp. 14-29.

- Kerry O'Brien December 10, 2003 7:30 Report, abc.net.au Archived 2010-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- G. Smith, Singing Australian: A History of Folk and Country Music (Pluto Press Australia, 2005), p. 2.

- Who'll come a waltzing Matilda with me?", The National Library of Australia, retrieved 14 March 2008.

- N. Cohen, Folk Music: a Regional Exploration (Greenwood, 2005), p. 297.

References and further reading

- Dugaw, Dianne. Deep Play: John Gay and the Invention of Modernity. Newark, Del.: University of Delaware Press, 2001. Print.

- Middleton, Richard (13 January 2015) [2001]. "Popular Music (I)". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Randel, Don (1986). The New Harvard Dictionary of Music. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-61525-5.

- Temperley, Nicholas (25 July 2013) [2001]. "Ballad (from Lat. ballare: 'to dance')". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Winton, Calhoun. John Gay and the London Theatre. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1993. Print.

- Witmer, Robert (14 October 2011) [20 January 2002]. "Ballad (jazz)". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Marcello Sorce Keller, "Sul castel di mirabel: Life of a Ballad in Oral Tradition and Choral Practice", Ethnomusicology, XXX(1986), no. 3, 449- 469.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ballads. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ballads |

- The British Literary Ballads Archive

- The Bodleian Library Ballad Collection: view facsimiles of printed ballads

- The English Broadside Ballad Archive: searchable database of ballad images, citations, and recordings

- Welsh Ballads resource guide

- The Traditional Ballad Index

- Black-letter Broadside Ballads Of The years 1595-1639 From the Collection of Samuel Pepys

- Smithsonian Global Sound: The Music of Poetry—audio samples of poems, hymns and songs in ballad meter.

- The Oxford Book of Ballads, complete 1910 book by Arthur Quiller-Couch

- English Broadside Ballad Archive—an archive of images and recordings of over 4,000 pre-1700 broadside ballads