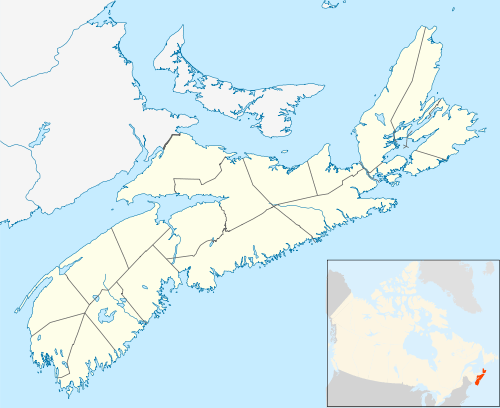

Baleine, Nova Scotia

Baleine (/beɪˈliːn/ bay-LEEN)[1] (formerly Port aux Baleines) is a community in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located in the Cape Breton Regional Municipality on Cape Breton Island. The community is perhaps best known as the landing site for pilot Beryl Markham's record flight across the Atlantic Ocean (See Memorial Plaque to Record Flight).

History

Sir Robert Gordon of Lochinar was one of the first to set out to establish Scottish colonies in America. On 8 November 1621 he obtained a royal charter of what was called the barony of Galloway in Nova Scotia, and in 1625 he published a tract on the subject. "Encouragements for such as shall have intention to bee Vndertakers in the new plantation...By mee Lochinvar...Edinburgh, 1625".[2]

Meanwhile, William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling, established the first incarnation of "New Scotland" at Port Royal.[3]

During the Anglo-French War (1627–1629), in the time of Charles I, by 1629 the Kirkes had taken Quebec City. On 1 July 1629, seventy Scots, led by James Stewart, 4th Lord Ochiltree, landed at Baleine on Cape Breton Island, probably encouraged by Sir Robert Gordon of Lochinar. Ochiltree arrived at Baleine with Brownists and built Fort Rosemar. It was a military colony, one that owed its origins to the exigencies of war, and not a permanent agricultural settlement. Ochiltree's primary objective was to erect a military post to assert King Charles's claims, and by extension the rights of the Merchant Adventures to Canada, in a crucial theatre that linked the St. Lawrence with Nova Scotia.[4] Ochiltree's party carried a good supply of guns, ammunition, and heavy artillery. One of its first actions was to attack and capture a sixty-ton Portuguese barque which they found at anchor near the site of their proposed settlement. The ship was dismantled and stripped of its cannon, which were then used as additional artillery to guard Fort Rosemar.[5] Ochiltree proceeded to capture French fishing vessels off the shores of Cape Breton.[6]

During this time, while Nova Scotia briefly became a Scottish colony, there were three battles between the Scots and the French: one at Saint John; another at Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour); and the other at Baleine. The series of English and Scottish triumphs left only Cape Sable (the present-day Port La Tour) as the only major French holding in North America, but this was not destined to last.[7] The haste of King Charles to make peace with France on the terms most beneficial to him meant that the new North American gains would be bargained away in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye of 1632.[3]

Siege of Baleine

Charles Daniel arrived with 53 men and numerous friendly natives. He captured two shallops manned by fishermen from Rosemar, and imprisoned them. On September 10, 1629 he approached the fort and assured the Scots he was coming in peace. The French then attacked by bombarding the fort with cannon fire from the ships and Daniel conducting a land assault.[8] Daniel was a harsh captor. He ordered Ochiltree and his company to demolish their fort and forced the prisoners to Grand Cibou (present-day Englishtown). There Daniel had Ochiltree and his men construct a new fort, Fort Sainte Anne. Then he sailed the prisoners to France, where Ochiltree was thrown in jail for a month.[9]

Naval blockade

During the French and Indian War, in the buildup to the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the British ran a naval blockade of Louisbourg off the coast of Baleine and Scatarie Island. Similarly the French were capturing British ships. Between August 1756 and October 1757, the French captured 39 British ships. The British pursued two French ships off of Scatarie Island: the Arc-en-Ciel (52 guns) and the frigate Concorde. The two ships had crossed the Atlantic together but got separated at the Grand Banks during a storm. The most significant single prize the British captured in 1756 was the Arc-en-Ciel. The ship was captured on 12 June off Scatarie after a long chase and a five-hour gun battle. The warship had on board sixty thousand livres in specie and as many as 200 recruits. The British kept the Arc-en-Ciel in Atlantic waters for the next few years, sailing out of Halifax. It would form part of the fleet the British put together to attack Louisbourg in 1758.[10]

At the same time, the Concorde initially eluded the Royal Navy on two occasions. The ship had 50 passengers made up of troops and stonemasons and 30 thousand livres in coin. On June 10 the Concorde slipped into the protected by on Scatarie Island. When it sailed out, the pursuit began anew. The Concorde headed for Port Dauphin (Englishtown) but eventually unloaded everyone and the money on board to a schooner that could safely make it to Louisbourg.[11]

References

- Endnotes

- The Canadian Press (2017), The Canadian Press Stylebook (18th ed.), Toronto: The Canadian Press

- Encovuagements, For fuch as shall have intention to bee Vnder-takers in the new plantation of Cape Briton now New Galloway in America. by mee Lochinvar. Edin. 1625 https://archive.org/stream/cihm_93615#page/n29/mode/2up

- Nichols, 2010. p. xix

- Nichols, 2010. p. 132

- Nichols, 2010. p. 133

- Nichols, 2010. p. 234

- Sarty & Knight (2003), p. 18.

- Nichols, 2010. p. 134

- Nichols, 2010. p. 135

- Johnston, 2007. p. 105-106.

- Johnston, 2007. p. 105-106.

- Bibliography

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2007) Endgame 1758. University of Cape Breton.

- Nicholls, Andrew. Showdown at Fort Rosemar: in 1629, sixty Scots landed on Cape Breton to begin the island's first Scottish settlement. The French were not amused. The Beaver: Exploring Canada's History. June 1, 2004

- Nicholls, Andrew (2010) A Fleeting Empire: Early Stuart Britain and the Merchant Adventures to Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Sarty, Roger and Doug Knight (2003) Saint John Fortifications: 1630-1956. New Brunswick Military Heritage Series.

- External links