Kwe people

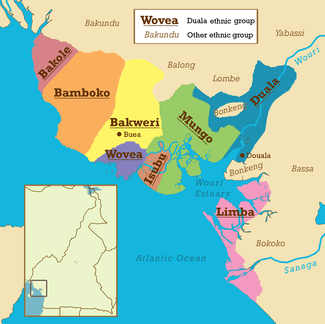

The Bakweri (or Kwe) are an ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. They are closely related to Cameroon's coastal peoples (the Sawa), particularly the Duala and Isubu.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Total: 32,200 (1982)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Cameroon | |

| Languages | |

| Mokpwe | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christian and/or ancestor worshippers | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bakole, Bamboko, Duala, Isubu, Limba, Mungo, Wovea |

History

Early population movements

According to Bakweri oral traditions, that they originated from Mboko, the area southwest of Mount Cameroon.[2] The Bakweri likely migrated to their present home east of the mountain in the mid-18th century. From the foothills, they gradually spread to the coast, and up the Mungo River and the various creeks that empty into it. In the process, they founded numerous villages, usually when individual families groups split off.[3] A rival Bakweri tradition says they descend from Mokuri or Mokule, a brother of the Duala's forebear Ewale, who migrated to the Mount Cameroon area for hunting.[4] In addition, a few isolated villages, such as Maumu and Bojongo, claim some alternate descent and may represent earlier groups whom the expanding Bakweri absorbed.[3]

European contacts

Portuguese traders reached the Cameroonian coast in 1472. Over the next few decades, more adventurers came to explore the estuary and the rivers that feed it, and to establish trading posts. The Bakweri provided materials to the coastal tribes, who acted as middlemen.

German administration

Germany annexed the Cameroons in 1884. In 1891, the Gbea Bakweri clan rose up in support of their traditional justice system when the Germans forbade them to use a trial by ordeal involving poison to determine whether a recent Christian convert was in fact a witch. This revolt was squelched with the razing of Buea in December 1894 and the death of Chief Kuv'a Likenye. The reprisals disunited the Bakweri, and they lost all rights under the German government.

The Germans initially ruled from Douala, which they called Kamerunstadt, but they moved their capital to the Bakweri settlement of Buea in 1901. The colonials' primary activity was the establishment of banana plantations in the fertile Mount Cameroon region. The Bakweri were impressed to work them, but their recalcitrance and small population led the colonials to encourage peoples from further inland, such as the Bamileke, to move to the coast. In addition, constant shipping traffic along the coast allowed individuals to move from one plantation or town to another in search of work. The Duala and Bakweri intermingled like never before.

British administrations

In 1918, Germany lost World War I, and her colonies became mandates of the League of Nations. Great Britain took control of Bakweri lands. Great Britain integrated its portion of Cameroon with the neighbouring colony of Nigeria, setting the new province's capital at Buea. The British practised a policy of indirect rule, entrusting greater powers to Bakweri chiefs in Buea.

The new colonials maintained the German policies of ousting uncooperative rulers and of impressing workers for the plantations.[5] Individuals could opt to pay a fine to avoid the labour, however, which led to a dearth of workers from the wealthier areas. The British thus renewed encouragement for people from the interior to move to the coast and work the plantations. Many Igbo from Nigeria entered the area, and the newcomers grew numerically and economically dominant over time. This led to ethnic tensions with the indigenes. Land expropriation was another problem, faced particularly in 1946.

A Bakwerian, Dr. E. M. L. Endeley was the first Prime Minister of the British Southern Cameroons from 1954–1959. He led other Southern Cameroonian parliamentarians to secede from the Nigerian Eastern House of Assembly in 1954.[6]

Geography

The Bakweri are primarily concentrated in Cameroon's Southwest Province. They live in over 100 villages[3] east and southeast of Mount Cameroon with Buea their main population centre. Bakweri settlements largely lie in the mountain's foothills and continue up its slopes as high as 4,000 metres.[3] They have further villages along the Mungo River and the creeks that feed into it. The town of Limbe is a mixture of Bakweri, Duala, and other ethnic groups.

There is an ongoing dispute between the Bakweri Land Claims Committee (BLCC) and the government of Cameroon regarding the disposition of Bakweri Lands formerly used by the Germans as plantations and now managed by the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC).[7]

Culture

The Bakweri today are divided into the urban and rural. Those who live in the cities such as Limbe and Buea earn a living at a number of skilled and unskilled professions. The rural Bakweri, in contrast, work as farmers, making use of Mount Cameroon's fertile volcanic soils to cultivate cocoyams, maize, manioc, oil palms, and plantains.

Traditional Bakweri society was divided into three strata. At the top were the native Bakweri, with full rights of land ownership. The next tier consisted either non-Bakweri or the descendants of slaves. Finally, the slaves made up the bottom rung. Chiefs and headmen sat at the pinnacle of this hierarchy in the past, though today such figures have very little power in their own right. Councils of elders and secret societies allow communities to decide important issues.[8]

Language

The Bakweri speak Mokpwe, a tongue that is closely related to Bakole and Wumboko.[9] Mokpwe is part of the family of Duala languages in the Bantu group of the Niger–Congo language family. Neighbouring peoples often utilise Mokpwe as a trade language, due largely to the spread of the tongue by early missionaries. This is particularly true among the Isubu, many of whom are bilingual in Duala or Mokpwe.[10] In addition, individuals who have attended school or lived in an urban centre usually speak Cameroonian Pidgin English or standard English. A growing number of the Bakweri today grow up with Pidgin as a more widely spoken language.[11] The Bakweri also used a drum language to convey news from clan to clan, and they also utilized a horn language peculiar to them.[12]

Marriage and kinship patterns

Bakweri inheritance is patrilineal; upon the father's death, his property is inherited by his eldest son. The Bakweri have traditionally practised polygamy, although with Christianisation, this custom has become extremely rare. In the traditional Bakweri society, women are chosen as future spouses when they are still children, and in some cases, even before they were born. The father or relative of the woman have been paid a dowry, thus the woman is considered as a property to the husband and his family. Upon the husband's death, the eldest surviving brother inherits the wife. A husband's prosperity was also intricately linked to the influence of his wife or wives. The wives tended his pigs, goats, cattle, arable land, so no one could trespass or exceed them, etc.[13]

Religion

The Bakweri have been largely Christianised since the 1970s. Evangelical denominations dominate, particularly the Baptist church. Christianity plays an important role in Bakweri regions, where music played over the radio is as likely to be the latest from Nigerian gospel singer Agatha Moses as it is the latest hit by a Nigerian music star.

Nevertheless, remnants of a pre-Christian ancestor worship persist. Traditional Bakweri belief states that the ancestors live in a parallel world and act as mediators between the living and God. As might be expected for coastal peoples, the sea also plays an important role in this faith. Spirits live in the forests and the sea, and many Bakweri believe that traditional practices hold a malign influence on everyday life. Traditional festivals held each year serve as the most visible expression of these traditional beliefs in modern times.[14]

Arts

The Bakweri still practice arts and crafts handed down for generations. The Bakweri are known to be skilled weavers of hats and shirts, for example. They also construct armoires, chairs, and tables.[13]

Bakweri dances serve a number of purposes. The Bakweri Male Dance, for example, demonstrates the performers' virility. Other dances are purely for enjoyment, such as the maringa and the ashiko, which arose in the 1930s, and the makossa and ambasse bey dances that accompany those musical styles.

The greatest venue for Bakweri music and dance are the two major festivals that take place each year in December. The Ngondo is a traditional festival of the Duala, although today all of Cameroon's coastal Sawa peoples are invited to participate. It originated as a means of training Duala children the skills of warfare. Now, however, the main focus is on communicating with the ancestors and asking them for guidance and protection for the future. The festivities also include armed combat, beauty pageants, pirogue races, and traditional wrestling.[14]

The Mpo'o brings together the Bakoko, Bakweri, and Limba at Edéa. The festival commemorates the ancestors and allows the participants to consider the problems facing the groups and humanity as a whole. Lively music, dancing, theatre, and recitals accompany the celebration.

Institutions

Assemblies, secret societies, and other groups play an important role in keeping the Bakweri unified, helping them set goals, and giving them a venue to find solutions to common problems.[15] Secret societies include the Leingu, Maalé (Elephant dance), Mbwaya, and Nganya.[15]

Classification

The Bakweri are Bantu in language and origin. More narrowly, they fall into the Sawa, or the coastal peoples of Cameroon.

Notes

- Ethnologue.

- Fanso 50-1.

- Fanso 50.

- Ngoh 27.

- Derrick 133.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 113–4.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 39.

- Ngoh 26, 28.

- "Mokpwe", Ethnologue.

- "Isu", Ethnologue.

- "Pidgin, Cameroon", Ethnologue.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Guide touristique 94.

- Guide touristique 126.

- Ngoh 28.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bakweri. |

- Chrispin, Dr. Pettang, directeur. Cameroun: Guide touristique. Paris: Les Éditions Wala.

- DeLancey, Mark W., and Mark Dike DeLancey (2000): Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press.

- Derrick, Jonathan (1990). "Colonial élitism in Cameroon: the case of the Duala in the 1930s". Introduction to the History of Cameroon in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Fanso, V. G. (1989). Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005): "Isu". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th ed. Dallas: SIL International. Accessed 6 June 2006.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005): "Mokpwe". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th ed. Dallas: SIL International. Accessed 6 June 2006.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005): "Pidgin, Cameroon". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th ed. Dallas: SIL International. Accessed 6 June 2006.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996). History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbe: Presbook.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ba-Kwiri. |

- Bakwerirama

- BakweriLands: The Essential Text and Documents of a Native Land (Bakweri Land Claims Committee website)

- Peuple Sawa (in French)