Backyard furnace

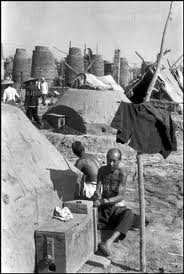

In China, backyard furnaces (土法炼钢) were small blast furnaces used by the people of China during the Great Leap Forward (1958–62).[1][2] These were constructed in the backyards of the communes, to further the Great Leap Forward's ideology of the rapid industrialization of China.

| Backyard furnace | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 土法煉鋼 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 土法炼钢 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | primitive steelmaking | ||||||

| |||||||

People used every type of fuel they could obtain to power these furnaces, from coal to the wood of coffins. Where iron ore was unavailable, they melted any steel objects they could get procure, including utensils, household objects like chairs and doors, bicycles, and even farming equipment, the intended end product being steel girders. The result was not steel, but high-carbon pig iron, which needs to be decarburized to make steel. Not until 1959 did the Party realize that only large industrial smelting plants were making steel of any value. Almost all of the iron from the communes was practically useless.

In regions where the steelmaking tradition had survived unbroken and the old skills of the ironmasters had not been forgotten, the pig iron was indeed further refined into steel, and steel production actually did increase. In regions that had no tradition of steelmaking, where the old ironmasters had been killed, or where there was no theoretical understanding of the blast-furnace process needed to refine pig iron, the results were unsatisfactory. At worst, the fuel used was high-sulfur coal, which produced pig iron that needed to be re-smelted and desulfurized before it could be refined into steel.

Even worse, the tending of the furnaces denied peasants the time and opportunity to produce food, effectively starving many and directly contributing to the Great Chinese Famine.

In Mao Zedong's opinion, despite the problems, backyard furnaces showed mass enthusiasm, mass creativity, and mass participation in economic development, despite the fact that this participation was not optional. Rather than dampen this mass movement, Mao encouraged it.[3] A central aspect of the ’Great Leap’ was the total mobilization of all able-bodied people in agricultural and industrial production. This included women, who were celebrated in their public role as ’iron women´ for their contributions to production.

See also

- Economy of China

- Video about Backyard Furnaces in China, 1958 (by PSB on Communism)

References

- Tyner, James A. (2012). Genocide and the Geographical Imagination. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9781442208995.

- Cook, Ian G.; Geoffrey Murray (2001). China's Third Revolution: Tensions in the Transition Towards a Post-Communist China. Routledge. pp. 53–55. ISBN 9780700713073.

- https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article41640