Backpage

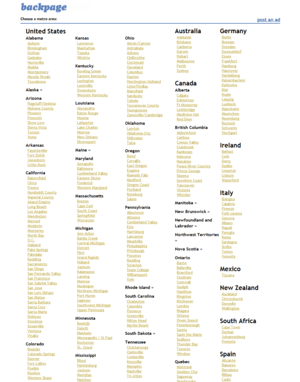

Backpage was a classified advertising website that had become the largest marketplace for buying and selling sex by the time that federal law enforcement agencies seized it in April 2018.[2][3]

| |

| Type of business | Web communications |

|---|---|

| Available in | English, Spanish, German, French, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Russian, Chinese, Finnish, Italian, Dutch, Swedish, and Turkish |

| Founded | 2004 |

| Owner | Atlantische Bedrijven CV Former owner: Village Voice Media |

| Employees | 120+ |

| Alexa rank | |

| Launched | 2004 |

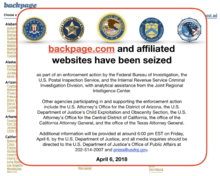

| Current status | Seized as of April 6, 2018 |

Backpage's adult services sections became the subject of an investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the United States Postal Inspection Service, the United States Department of Justice,[4] the Internal Revenue Service Criminal Investigator Division, with analytical assistance from the Joint Regional Intelligence Center over accusations that the website knowingly allowed and encouraged users to post ads related to prostitution and human trafficking, particularly involving minors, and took steps to intentionally obfuscate the activities.

Its CEO, Carl Ferrer, pleaded guilty to charges of facilitating prostitution and money laundering, acknowledging that "the great majority” of the adult advertisements on Backpage were actually advertisements for prostitution. As part of his plea agreement Ferrer agreed to shut down the site and give its data to law enforcement.[5]

History

Backpage was launched in 2004 by New Times Media (later to be known as Village Voice Media), a publisher of 11 alternative newsweeklies, as a free classified advertising website.[6]

Backpage soon became the second largest online classified site in the United States.[6] The site included the various categories found in newspaper classified sections including those that were unique to and part of the First Amendment-driven traditions of most alternative weeklies. These included personals (including adult-oriented personal ads), adult services, musicians and "New Age" services.

Adult section

Until January 9, 2017, Backpage contained an adult section containing different subcategories of various sex work. The company suspended its adult listings following accusations by a United States Senate subcommittee of being directly involved with sex-trafficking and the sexual exploitation of minors.[7] However, many escorts and erotic masseuses admit to moving their ads to the "massage" and "women seeking men" listings.[8] Prostitution is illegal throughout the United States, except for some counties in Nevada.

Kristen DiAngelo, executive director of the Sex Workers Outreach Project of Sacramento, criticized the shutdown, questioning how many sex workers across the United States no longer had a way to support themselves. Backpage allowed for sex workers using the site to post bad date lists, screen clients and communicate with other sex workers to ensure a safer experience.[9] Activists argued that the move would force some of the site's users to work on the street instead.[10]

Controversy

As early as 2011 critics and law enforcement began accusing Backpage of being a hub for sex trafficking of both adults and minors.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] despite claims by the website that it sought to block ads suspected of child sex trafficking or prostitution[11] and reported some per month to the NCMEC, which in turn notified law enforcement.[12][13]

In 2015 Backpage lost all credit card processing agreements as banks came under pressure from law enforcement, leaving Bitcoin as the remaining option for paid ads.

Backpage supporters claimed that by providing prompt and detailed information about suspicious postings to law enforcement, including phone numbers, credit card numbers and IP addresses, the website helped protect minors from trafficking. They contended that shutting down Backpage would drive traffickers to other places on the internet that will be less forthcoming about crucial information for law enforcement.[15][18][19]

Numerous writers, non-governmental organizations ("NGO's") legal experts and law enforcement officials including the Electronic Frontier Foundation,[20][21] the Internet Archive,[22] and the Cato Institute,[23] argued that the freedoms and potentially the internet itself would be threatened if this type of free speech is prohibited on Backpage. They cite both First Amendment rights of free speech guaranteed in the Constitution as well as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act,[24] which holds that service providers were not liable for content produced by third parties.[24][25]

In 2012, at the behest of a number of NGO's including Fair Girls and NCMEC, Fitzgibbon Media (a well-known progressive/liberal public relations agency) created a multimedia campaign to garner support for the anti-Backpage position. They enlisted support from musicians, politicians, journalists, media companies and retailers. The campaign created a greater public dialogue, both pro and con, regarding Backpage.[26] Some companies including H&M, IKEA, and Barnes & Noble canceled ads for publications owned by Village Voice Media. Over 230,000 people including 600 religious leaders, 51 attorneys general, 19 U.S. senators, over 50 non-governmental associations, musician Alicia Keys, and members of R.E.M., The Roots, and Alabama Shakes petitioned the website to remove sexual content.[14] New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof authored a number of columns criticizing Backpage,[27][28][29] to which Backpage publicly responded.[30]

In 2012, Village Voice Media separated its newspaper company, which then consisted of eleven weekly alternative newspapers and their affiliated web properties, from Backpage, leaving Backpage in control of shareholders Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin. Executives for the spinoff holding company, called Voice Media Group (VMG) and based in Denver, raised "some money from private investors" in order to purchase the newspapers;[31] the executives who formed the new company were lower-ranked than Lacey and Larkin.[32] In December 2014, Village Voice Media sold Backpage to a Dutch holding company. Carl Ferrer, the founder of Backpage, remained as CEO of the company.[33] Michael Hardy of the Texas Observer stated that since Lacey and Larkin remained at Backpage, "it would be more accurate to say that Backpage spun off Village Voice Media."[32]

Legal decisions

Beginning in 2011 a number of legal challenges were brought in attempts to eliminate the adult section of Backpage or shut down the website entirely. Backpage successfully argued that the First Amendment protections of free speech would be compromised by any restriction on postings by individuals on the Backpage website.

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA) served as an additional cornerstone in the defense. Section 230 says that "No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider." This portion of the CDA was drafted to protect ISPs and other interactive service providers on the Internet from liability for content originating from third parties.[34] The enactment of this portion of the CDA overturned the decision in Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Services Co. in which Prodigy was deemed by the court to be a publisher and therefore liable for content posted on its site.[34] Many observers have credited the passage of section 230 of the CDA as the spark that ignited the explosive growth of the internet.[24] The protection afforded to website owners under section 230 was upheld in numerous court cases subsequent to the passage of the legislation in 1996 including Doe v. MySpace Inc., 528 F.3d 413 (5th Cir. 2008) and Dart v. Craigslist, Inc., 665 F. Supp. 2d 961 (N.D. Ill. October 20, 2009)

Alleged victims

On April 9, 2018, the US Department of Justice's indictment against Backpage was unsealed. It contains details about 17 alleged victims who range from minors as young as 14 years old to adults, who were allegedly trafficked on the site while Backpage was knowingly facilitating prostitution. One 15-year-old is alleged to have been forced to do in-calls at hotels. A second teenager was allegedly told to "perform sexual acts at gunpoint and choked" until she had seizures, before being gang raped. A third victim, advertised under the pseudonym "Nadia" was stabbed to death, while a fourth victim was murdered in 2015, and her corpse deliberately burned. The lawyer for Backpage operations manager Andrew Padilla stated that his client was "not legally responsible for any actions of third parties under U.S. law. He is no more responsible than the owner of a community billboard when someone places an ad on it".[35][36]

In October 2018, a Texas woman sued Backpage and Facebook, claiming she had been sex trafficked on Backpage by a man who lured her into prostitution by posing as her friend on the social media network.[37]

On April 15, 2019, a Wisconsin man was convicted on federal sex trafficking charges over victims who he brought across state lines, forced into prostitution and advertised on Backpage.[38]

On April 29, 2019, a Florida former middle school teacher was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison for buying sex with a 14-year-old girl who was advertised on Backpage.[39]

Arrest of CEO and corporate officers

On October 6, 2016, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and California Attorney General Kamala Harris announced that Texas authorities had raided the Dallas headquarters of Backpage.com and arrested CEO Carl Ferrer at the George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston on felony charges of pimping a minor, pimping, and conspiracy to commit pimping. The California arrest warrant alleged that 99% of Backpage's revenue was directly attributable to prostitution-related ads, and many of the ads involved victims of sex trafficking, including children under the age of 18. The State of Texas was also considering a money laundering charge pending its investigation.[40][41] Arrest warrants were also issued against former Backpage owners and founders Michael Lacey and James Larkin. Lacey and Larkin were charged with conspiracy to commit pimping.[42][43]

Backpage general counsel Liz McDougall dismissed the raid as an "election year stunt" which wasn't "a good-faith action by law enforcement", and said that the company would "take all steps necessary to end this frivolous prosecution and will pursue its full remedies under federal law against the state actors who chose to ignore the law, as it has done successfully in other cases."[44] Backpage also accused California attorney general Kamala Harris of an illegal prosecution.[45]

On October 17, attorneys for Ferrer, Larkin and Lacey, sent a letter to Harris asking that all charges against their clients be dropped.[46] Harris refused.

On December 9, 2016, Superior Court Judge Michael Bowman dismissed all the charges in the complaint, stating that: "...Congress has precluded liability for online publishers for the action of publishing third party speech and thus provided for both a foreclosure from prosecution and an affirmative defense at trial. Congress has spoken on this matter and it is for Congress, not this Court, to revisit.”[47]

On December 23, 2016, the state of California filed new charges against Backpage CEO Carl Ferrer and former Backpage owners Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin accusing them of pimping and money laundering.[48] Lawyers for Backpage responded that the charges rehashed the earlier case that had been dismissed.

Since April 2015, the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations ("PSI") has been investigating Backpage.com as part of a stated overall investigation of human trafficking. After a voluntary, day-long briefing and interview provided by the company's General Counsel, PSI followed up with a subpoena to Backpage.com demanding over 40 categories of documents, covering 120 subjects, regarding Backpage's business practices. Much of the subpoena targeted Backpage's editorial functions as an online intermediary. Over the ensuing months, Backpage raised and PSI rejected numerous objections to the subpoena, including that the subpoena was impermissibly burdensome both in the volume of documents PSI demanded and in its intrusion into constitutionally-protected editorial discretion. PSI subsequently issued a shorter document subpoena with only eight requests but broader in scope and also targeting Backpage.com's editorial functions. Backpage.com continued to object on First Amendment and other grounds.

PSI applied in March 2016 for a federal court order to enforce three of the eight categories of documents in the subpoena. In August 2016, the U.S. District Court in D.C. granted PSI's application and ordered Backpage to produce documents responsive to the three requests.[49]

Backpage immediately filed an appeal and sought a stay, which the district court denied, then filed emergency stay petitions with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, and Supreme Court. Each appellate court issued temporary stays to consider whether to grant a stay pending appeal,[50] but eventually denied the emergency stay requests,[51] However, the D.C. Circuit agreed to expedite the appeal, and one of its judges who considered the emergency stay said he would have granted it. Backpage has continued to pursue its appeal despite producing thousands of documents to PSI pursuant to the District Court order. PSI scheduled a Subcommittee hearing regarding Backpage.com for January 10, 2017.

Also on January 9, 2017, prior to its scheduled hearings on Backpage the next day, the PSI released a report that accused Backpage of knowingly facilitating child sex trafficking.[52][53]

Shortly thereafter, Backpage announced that it would remove its adult sections from all of its sites in the United States. Backpage said it was taking this action due to many years of continuing acts by the government to unconstitutionally censor the site's content via harassment and extra-legal tactics and to make it too costly to continue its publishing activities.[54][55]

In late March 2018 and early April 2018, courts in Massachusetts and Florida affirmed that Backpage's facilitation of sex trafficking fell outside of the immunity granted by Section 230 safe harbors. The latter ruling argued that because Backpage "materially contributed to the content of the advertisement" by censoring specific keywords, it became a publisher of content and thus no longer protected.[56][57]

On April 9, 2018, the US Department of Justice's indictment against Backpage was unsealed.[58][35] The 93 charges included "Crimes of conspiracy to facilitate prostitution using a facility in interstate or foreign commerce, facilitating prostitution using a facility in interstate or foreign commerce, conspiracy to commit money laundering, concealment money laundering, international promotional money laundering, and transactional money laundering."[59][60] According to prosecutors, the seven people charged in the indictment are: Michael Lacey of Paradise Valley, Arizona; James Larkin of Paradise Valley, Arizona; Scott Spear of Scottsdale, Arizona; John E. "Jed" Brunst of Phoenix, Arizona; Daniel Hyer of Dallas, Texas; Andrew Padilla of Plano, Texas; and of Addison, Texas.[59][61]

Seizure

On April 6, 2018, Backpage was seized by the United States Department of Justice, and it was reported that Michael Lacey's home had been raided by authorities.[62] Lacey was charged with money laundering and violations of the Travel Act.[63][64][65][66]

A study conducted one year after Backpage was shut down found that the website had owned a virtual monopoly on Internet prostitution. The report Childsafe.AI, found that demand remains lower as sex trafficking has become more difficult and less profitable on the Internet.[67]

Guilty pleas

On April 12, 2018, Carl Ferrer, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Backpage pleaded guilty to both state and federal charges, including but not limited to conspiracy to facilitate prostitution and money laundering.[68] He also agreed to a plea deal in which he will testify against other alleged co-conspirators, such as but not limited to founders Michael Lacey and James Larkin.[69][70][71] Backpage also pleaded guilty to human trafficking.[69][70][71]

See Also

- I am Jane Doe documentary (2017)

References

- Alexa.com (January 20, 2016). "Backpage site statistics". Alexa Internet. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- "Exclusive: Report gives glimpse into murky world of U.S..." Reuters. April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Noah (July 24, 2020). "28 Best Backpage Alternative Websites (2020 Update)". Alternativoj. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Backpage.com CEO pleads guilty to California money charges". Business Insider. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Astor, Maggie (April 12, 2018). "Backpage Chief Pleads Guilty to Conspiracy and Money Laundering". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- Kiefer, Michael (September 23, 2012), Phoenix New Times founders selling company, Phoenix: The Arizona Republic, retrieved December 1, 2015

- "Backpage pulls adult ads and accuses government of 'censorship'". NBC News. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- Salinger, Alexa (2017). The Ultimate Guide to Backpage Ads (1st ed.). New York: Amazon Digital Services. p. 38. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Nedelman, Michael (April 10, 2018). "After Craigslist personals go dark, sex workers fear what's next". CNN.

- Levin, Sam (January 10, 2017). "Backpage's halt of adult classifieds will endanger sex workers, advocates warn". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

-

Manuel Gamiz Jr. (July 12, 2014). "Website fuels surge in prostitution, police say". The Morning Call. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

Backpage.com was formed in 2004, but didn't factor much in vice investigations until its adult services section flooded with ads around 2010, the same year Craigslist stopped its adult section.

-

Roy S. Johnson (January 25, 2017). "Sex Trafficking Victim Sues Backpage.com, Choice Hotels". Alabama.com. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

Last September, however, the Supreme Court in Washington state ruled 6-3 that a 2012 suit against Backpage.com by three Washington teenaged girls who were allegedly trafficked on the site, could proceed, in what turned out to be a preliminary blow against the site.

Backpage was seized by the federal government on April 6, 2018. - "Amicus Curiae Brief of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Feyerick, Deborah; Steffen, Sheila (May 10, 2012). "A lurid journey through Backpage.com". CNN.com. cnn.com. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Irvine, Martha (August 16, 2015). "Backpage ad site: Aider of traffickers, or way to stop them?". Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Fisher, Daniel. "Backpage Takes Heat, But Prostitution Ads Are Everywhere". Forbes. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Kristof, Nicholas (January 25, 2012). "Opinion | How Pimps Use the Web to Sell Girls". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Ruvolo, Julie (June 26, 2012). "Sex, Lies and Suicide: What's Wrong with the War on Sex Trafficking". Forbes. Forbes. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Charles, J.B. (November 17, 2016). "America's top online brothel a critical tool for law enforcement". TheHill. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Washington State Drops Defense of Unconstitutional Sex Trafficking Law". www.eff.org. Electronic Frontier Foundation. December 6, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- Reitman, Rainey (July 6, 2015). "Caving to Government Pressure, Visa and MasterCard Shut Down Payments to Backpage.com". www.eff.org. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- (United States District Court, Western District of Washington at Seattle December 10, 2012). Text

- Backpage v Dart (United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit October 23, 2015). Text

- Masnick, Mike (February 8, 2016). "20 Years Ago Today: The Most Important Law On The Internet Was Signed, Almost By Accident". www.techdirt.com. Techdirt. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- Goldman, Eric (July 30, 2016). "Overzealous Legislative Effort Against Online Child Prostitution Ads at Backpage Fails, Providing a Big Win for User-Generated Content". www.forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "Exposing Backpage.com". www.fitzgibbonmedia.com. Fitzgibbon Media. Archived from the original on January 16, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Kristof, Nicholas (November 1, 2014). "Teenagers Stand Up to Backpage". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Kristof, Nicholas (March 17, 2012). "Where Pimps Peddle Their Goods". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Kristof, Nicholas (March 31, 2012). "Financers and Sex Trafficking". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- "What Nick Kristof Didn't Tell You in his Sunday Column about Backpage.com". www.villagevoice.com. Village Voice. March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- Francescani, Chris; Nadia Damouni (September 24, 2012). "Village Voice newspaper chain to split from controversial ad site". Reuters. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- Hardy, Michael (December 14, 2017). "Requiem for an Alt-Weekly". Texas Observer. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- Kezar, Korri (December 30, 2014), Backpage.com sold to Dutch company for undisclosed amount, Dallas: Dallas Business Journal, retrieved December 1, 2015

- Ehrlich, Paul (January 1, 2002). "Communications Decency Act 230". Berkeley Technology Law Journal. 17 (1). Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Lynch, Sarah N. (April 9, 2018). "Backpage.com founders, others indicted on prostitution-related charges". Reuters. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Amatulli, Jenna; Reilly, Ryan J. (April 9, 2018). "Backpage.com Founders Indicted For Facilitating Prostitution On Site". HuffPost Canada. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Whitcomb, Dan. "Woman sues Facebook, claims site enabled sex trafficking". U.S. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- "Wisconsin man found guilty of sex trafficking on now-defunct..." Reuters. April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- "Florida man imprisoned for trafficking girl, 14, via Backpage.com". Reuters. April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- "Backpage CEO to appear in Houston court on prostitution bust". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Attorney General Kamala D. Harris Announces Criminal Charges Against Senior Corporate Officers of Backpage.com for Profiting from Prostitution and Arrest of Carl Ferrer, CEO". State of California - Department of Justice - Kamala D. Harris Attorney General. October 6, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Mele, Christopher (October 6, 2016). "C.E.O. of Backpage.com, Known for Escort Ads, Is Charged with Pimping a Minor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Backpage.com raided, CEO arrested for sex-trafficking". The Big Story. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Hamilton, Matt. "Backpage says criminal charges by Kamala Harris are 'election year stunt'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Backpage.com CEO Will Fight Sex Trafficking Charges, Lawyer Says". CBS Los Angeles. October 7, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- James C. Grant (October 17, 2016). "The Honorable Kamala D. Harris Re: People v. Ferrer, et al., Case No. 16FE019224 (Sup. Ct., Sacramento County)" (PDF). Davis Wright Tremaine. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- California vs Ferrar, et al (Cal. Super December 9, 2016) ("Congress has precluded liability for online publishers for the action of publishing third party speech and thus provided for both a foreclosure from prosecution and an affirmative defense at trial. Congress has spoken on this matter and it is for Congress, not this Court, to revisit."). Text

- "California v. Ferrer" (PDF). December 23, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Senate Permanent Committee on Investigations v. Ferrer, __ F.Supp.3d ___, 2016 WL 4179289, Misc. Action No. 16-mc-621 (RMC) (D.D.C. August 16, 2016).

- Ferrer v. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 137 S. Ct. 1 (Mem.), 195 L.E.2d 900, 85 USLW 3075 (Sep 6, 2016),

- Ferrer v. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, 137 S. Ct. 28 (Mem.), 195 L.E.2d 901, 85 USLW 3084 (Sep 13, 2016).

- "Backpage.com's knowing facilitation of online sex trafficking" (PDF). United States Senate, PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Neidig, Harper (January 10, 2017). "Senators blast Backpage executives as site closes adult section". TheHill. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "Backpage.com shuts down adult services ads after relentless pressure from authorities". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "Backpage Kills Adult Ads On The Same Day Supreme Court Backed Its Legal Protections, Due To Grandstanding Senators". Techdirt. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "Court Shows SESTA Is Not Needed: Says Backpage Can Lose Its CDA 230 Protections If It Helped Create Illegal Content". Techdirt. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Yet Another Court Says Victims Don't Need SESTA/FOSTA To Go After Backpage". Techdirt. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- Brice, Makini; Mason, Jeff; Oatis, Jonathan (April 11, 2018). "Trump signs law to punish websites for sex trafficking". Reuters. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- Bhardwaj, Prachi (April 9, 2018). "Backpage.com executives have been charged with a 93-count federal indictment that alleges conspiracy to facilitate prostitution and money laundering". Business Insider. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Heater, Brian (April 9, 2018). "DOJ issues 93-count indictment against Backpage over sex ads – TechCrunch". TechCrunch. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Thomson, Iain (April 12, 2018). "Backpage.com swoop: Seven bods hit with 93 charges as AG Sessions blasts alleged child sex trafficking cyber-haven". The Register. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- Polti, Daniel (April 7, 2018). "Feds Seize Backpage.com, Slap Charges on Founder of Site Accused of Profiting From Prostitution". Slate.

- "Federal Backpage Indictment Shows SESTA Unnecessary, Contains Zero Sex Trafficking Charges". Techdirt. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- "The feds have seized classifieds website Backpage". The Verge. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- Tanfani, Joseph. "Federal authorities take down Backpage.com, site accused of being a haven for online prostitution". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "DOJ Seizes And Shuts Down Backpage.com (Before SESTA Has Even Been Signed)". Techdirt. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Exclusive: Report gives glimpse into murky world of U.S..." Reuters. April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Jackman, Tom (April 13, 2018). "Backpage CEO Carl Ferrer pleads guilty in three states, agrees to testify against other website officials". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- "Backpage.com and its CEO plead guilty in California and Texas". Los Angeles Times. April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- Kreps, Daniel (April 12, 2018). "Backpage CEO Pleads Guilty to Charges, Assists in Federal Investigation". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- Chamberlain, Samuel (April 12, 2018). "Backpage.com, CEO plead guilty in California, Texas and Arizona". Fox News. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- Jackman, Tom (August 1, 2017). "Senate launches bill to remove immunity for websites hosting illegal content, spurred by Backpage.com". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- "Secret Memos Show the Government Has Been Lying About Backpage All Along". Reason.com. August 26, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Reason Magazine, Katherine Mangu-Ward. "Backpage DOJ 2012 Memo". www.documentcloud.org. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Reason Magazine, Katherine Mangu-Ward. "Backpage DOJ 2013 Memo". www.documentcloud.org. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

External links

- Backpage.com seized by feds over sex trafficking ads. CBS Evening News. April 6, 2018.