Bakhmut

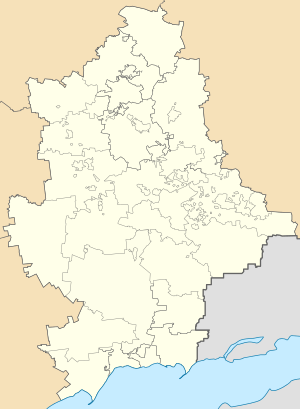

Bakhmut (Ukrainian: Ба́хмут, Russian: Бахму́т) formerly Artemivsk/Artyomovsk (Ukrainian: Артемівськ, Russian: Артёмовск), is a city of regional significance in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. On 4 February 2016 the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine confirmed the name change of the city by returning to the original one.[4][5] The city serves as an administrative center of Bakhmut Raion although it does not belong to the raion. It is located on the Bakhmutka River about 89 km away from the administrative center of the Donetsk Oblast, Donetsk. Population: 77,177 (2015 est.)[3]

Bakhmut Бахмут | |

|---|---|

Bakhmut skyline | |

.svg.png) Flag  Coat of arms | |

Bakhmut  Bakhmut | |

| Coordinates: 48°35′29″N 38°4′50″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Founded | before 1571 |

| City rights | 1783[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Oleksiy Reva (since 1990)[2] |

| Area | 41.6 km2 (16.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) |

| Population (2015) | 77,177[3] |

| Climate | Dfb |

Bakhmut was a capital of Slavo-Serbia, which was established by Serbian migrants from Austria. In 1920–24, the city was an administrative center of Donets Governorate of the Ukrainian SSR.

History

There is evidence of prior settlement in 1556. However, officially it was mentioned in 1571 as a guard-fort (storozha) located at mouth of river Chornyi Zherebets and named as Bakhmut after another river Bakhmutka (a tributary of the Seversky Donets) on which it is situated.[6] The settlement initially began as a border point and was later turned into a fortification.[6] The name is believed to be derived from Tatar name Mahmud or Mahmet.[6] The history of the town before 18th century is sparse. In 1701, Peter I ordered to build a fortress in place of fort and transform the adjacent sloboda (free village) as a city of Bakhmut.[6] The fort was completed in 1703. At that time it accounted for 170 people.[6] In 1704 Peter the Great issued a certificate for Ukrainian Cossacks to settle at Bakhmutka river and mine a salt.[6] The city population increased two-fold and the town was assigned to the Izium Regiment (a province of Sloboda Ukraine).[6]

In the autumn of 1705, a detachment of Cossacks headed by Ataman Kondraty Bulavin captured the Bakhmut salt mines,[7] which later caused the town to be one of the centers of the Bulavin Rebellion, and held the city until March 7, 1708 when it was seized by government troops. From 1708 to April 22, 1725, Bakhmut is situated in the Azov Governorate, and on May 29, 1719 becomes the administrative center of Bakhmut Province within the governorate.[8] From 1753 to 1764, it was a main city of the Slavo-Serbia territory inhabited by colonists from Serbia and elsewhere.

In 1783, Bakhmut received city status within the Yekaterinoslav province (Novorossiysk Governorate).[9] During this time, in the city, there were 49 houses, five brick, candle, and soap factories. The city had about 150 shops, a hospital, and three schools: two private boarding schools for children of wealthy parents, and a Sunday school for children of workers. Bakhmut had a large shopping center. There twice a year, on July 12 (Day of the Apostles Peter and Paul) and September 21 (Day of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary), big fairs were conducted. The city's annual turnover was about 1 million rubles. On August 2, 1811, the city emblem was approved. In 1875, a water-system was installed.

On January 25, 1851, the city became a municipality, with Vasily I. Pershin as mayor. In 1876, within the Bakhmut Basin were discovered large deposits of rock salt, which was followed by a rapid increase in the numbers of mines, with salt productions reaching 12% nationwide. After the construction of a rail route Kharkov-Bakhmut-Popasnaya, there was enterprise for the production of alabaster, plaster, brick, tile, and soda ash. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the city developed metal-working. By 1900, the city had 76 small industrial enterprises, which employed 1,078 workers, as well as four salt mines, which employed 874 workers. In 1900, the streets became paved. By 1913, the population consisted of 28,000 people. There were two hospitals with 210 beds, four secondary and two vocational schools, six single-class schools, four parish schools, and a private library.

In April 1918 troops loyal to the Ukrainian People's Republic took control of Bakhmut.[10]

On December 27, 1919, Soviet power is established within the city. In 1923, there were 36 enterprises, including a factory "Victory of Labor" (a former nail-spike factory), a factory "Lightning" that produced castings for agriculture, as well as brick, tile, and alabaster factories; mines "Karl Liebknecht and Sverdlov", "Shevchenko", and "Bakhmut salt"; and a shoe factory. From April 16, 1920 to August 1, 1925, Bakhmut is the administrative center of the Donetsk province.

In 1924 the city's name was changed from Bakhmut to Artemivsk, in honour of Artyom, a Russian Bolshevik (Communist) revolutionary figure who lived and worked in the city in the early years of the revolution. In 1938, Moskalenko is the First Secretary of the Municipal Committee of the CPU. In 1941, Vasily Panteleevich Prokopenko is First Secretary of the City Committee of the Communist Party.

From October 31, 1941 to May 9, 1943, German troops occupied Artemivsk under the command of Von Zobel. Under occupation in 1941, Nikolai Mikhailovich Zhorov was the Secretary of the underground City Party Committee.

In early 1942, during the Nazi occupation, German Einsatzgruppe C took some 3,000 Jews from the town to a mine shaft two kilometres outside of town and shot into the crowd, killing several people; the Germans then bricked up the tunnel, suffocating all inside.[11]

In 1961, Kuzma Petrovich Golovko became First Secretary of City Party Committee, followed by Ivan Malyukin in 1966, Nikolai S. Tagan in 1976, and Yuri K. Smirnov from 1980 to 1983. From April 1990 to 1994, Alexei Reva was Chairman of City Council and was elected mayor in 1994.[12]

In January 1999, a charitable Jewish foundation in Bakhmut, the city council and a winery that had opened on the site in 1952, inaugurated a memorial to commemorate the victims of the 1942 mass murder. The memorial was built into a rock face in the old mine where water collects and was named the "Wailing Wall" for the murdered Jews of Bakhmut.[11]

During the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine, the militants of Donetsk People's Republic declared the city part of the republic by pro-Russian separatists.[13][14] The city was eventually retaken by Ukrainian forces on 7 July 2014, along with Druzhkivka.[15][16]

On 15 May 2015 President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko signed a bill into law that started a six months period for the removal of communist monuments and the mandatory renaming of settlements with a name related to Communism.[17]

On 23 September 2015 the city council voted for renaming the city back to Bakhmut (for - 31, against - 8, abstain - 3, did not vote - 3).[18] The final decision was made by the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's national parliament) on 4 February 2016.[4][5]

Name change

- 1571 - 1924 Bakhmut

- 1924 - 1941 Artyomovsk / Artemivsk (Artemivsk until 1930s)

- 1942 - 1943 Bakhmut

- 1943 - 1992 Artyomovsk / Artemivsk

- 1992 - 2016 Artemivsk

- 2016–present Bakhmut

Demographics

As of June 1, 2017 the population of Bakhmut was 75.9 thousand people.[19]

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, the majority of residents are ethnic Ukrainians and speak Russian as a first language:[20][21]

| Ethnicity | |

| Ukrainians | 69.4% |

| Russians | 27.5% |

| Belarusians | 0.6% |

| Armenians | 0.3% |

| Roma | 0.2% |

| Jews | 0.2% |

| Language | |

| Russian | 62% |

| Ukrainian | 35% |

| Armenian | 0.19% |

| Romani | 0.15% |

| Belarusian | 0.10% |

Economy

Since 1951, the European Bakhmut Winery is located in the city. The Artyomsol salt mine is located in the suburb of Soledar, which contains the world's largest underground room. It is large enough that a hot air balloon has been floated inside, symphonies have been played before, and two professional soccer matches have been held at the same time. It is large enough to fit Notre Dame inside with room to spare.

Transport

The highways of Kharkiv-Rostov and Donetsk-Kiev run through Bakhmut. The towns of Chasiv Yar and Soledar are included in the Bakhmut municipality. The city has a public transport system consisting of a network of trolleybuses and buses.

Education

There are 20 schools (11,600 students), 29 kindergartens (3500 children), 4 vocational schools (2,000 students), 2 technical schools (6,000 students), and several music schools. Some include:

- Artemovsk Industrial College (Tchaikovsky Street)

- Donetsk Musical College named John Karabits (Lermontov Street)

- Donetsk Pedagogical School (St. Annunciation)

- Donetsk Medical School (St. W. Nosakova)

- Artemovsk professional school (St. Defence)

Culture

- Artemovsk City Center Children and Youth (Artema Street)

- Artemovsk city center of culture and recreation (Svoboda)

- Artemovsk City Folk House (Victory Street)

- Building Technology "Donetskgeologiya" (St. Sibirtzev)

- Palace of Culture "mechanician" (Artema Street)

See also

- Bulavin Rebellion

- Gavrila Kropotov

- Szydlowski

References

- http://artemrada.gov.ua/uk/history/

- (in Ukrainian) Keys to cities. What is the secret of longevity of mayors, The Ukrainian Week (10 August 2020)

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Decommunisation continues: Rada renames several towns and villages, UNIAN (4 February 2016)

- "Rada de-communized Artemivsk as well as over hundred cities and villages" (in Ukrainian). Ukrayinska Pravda. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Artemivsk (Артемівськ). The History of cities and villages of the Ukrainian SSR.

- Rebellion of peasants and Cossacks under the leadership of Bulavin (in Russian)

- "Інститут історії України НАН України". history.org.ua. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia Dictionary (in Russian). 1903.

- (in Ukrainian) 100 years ago Bakhmut and the rest of Donbass liberated, Ukrayinska Pravda (18 April 2018)

- ""Wailing Wall" for the murdered Jews of Bakhmut: Remembrance". Information Portal to European Sites of Remembrance. Berlin, Germany: Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- A chronological list of events in the history of Artemovsk Archived 2008-10-30 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- Leonid Ragozin. "Putin Is Accidentally Helping Unite Eastern and Western Ukraine - The New Republic". The New Republic. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- "TASS: World - Donbass defenders put WWII tank back into service". TASS. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- "BBC News - Ukraine crisis: Bridges destroyed outside Donetsk". BBC News. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- "Ukraine flag raised over two cities, military tells Poroshenko". Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunization. Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes, Interfax-Ukraine. 15 May 20

Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols, BBC News (14 April 2015) - Renaming city and streets. Artemivsk city council website. 23 September 2015

- "Количество жителей Бахмута продолжает сокращаться" Vecherniy Bakhmut, September 5, 2017

- Національний склад та рідна мова населення Донецької області. Розподіл постійного населення за найбільш численними національностями та рідною мовою по міськрадах та районах.

- "Ukrcensus.gov.ua". ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bakhmut. |

- (in English) Artemivsk at the Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- (in Russian) City portal

- (in Ukrainian) Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine

- (in Ukrainian) City council website