United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races

The United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races (FULRO; French: Front unifié de lutte des races opprimées, Vietnamese: Mặt trận Thống nhất Đấu tranh của các Sắc tộc bị Áp bức) was an organization whose objective was autonomy for the Degar tribes in Vietnam. Initially a political movement, after 1969 it evolved into a fragmented guerrilla group that carried on insurgencies against, successively, the governments of South Vietnam and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Opposed to all forms of Vietnamese rule, FULRO fought against the Viet Cong and ARVN at the same time. FULRO's primary supporter was Cambodia, with some aid sent by China.

| United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races | |

|---|---|

Front unifié de lutte des races opprimées Participant in the FULRO insurgency against Vietnam, the Vietnam War, and the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia | |

| |

| Active | 1964–1992 |

| Leaders | FLC leader: Les Kosem, Po Dharma[1] FLHP leader: Y Bham Enuol FLKK leader: Chau Dera |

| Area of operations | Central Highlands, Vietnam Mondulkiri Province, Cambodia |

| Allies | |

| Opponent(s) | |

The movement effectively ceased in 1992, when the last group of 407 FULRO fighters and their families handed in their weapons to United Nations peacekeepers in Cambodia.

BAJARAKA – precursor of FULRO

On May 1, 1958, a group of intellectuals headed by a French-educated Rhade civil servant, Y Bham Enuol, established an organization seeking greater autonomy for the minorities of the Vietnamese Central Highlands. The organization was given the name BAJARAKA, which stood for four main ethnic groups: the Bahnar people, the Jarai, the Rhade people, and the Koho people.

On July 25, BAJARAKA issued a notice to the embassies of France and the United States and to the United Nations, denouncing acts of racial discrimination, and requesting government intervention to secure independence. In August–September 1958, BAJARAKA held several demonstrations in Kon Tum, Pleiku, and Buôn Ma Thuột. These were quickly suppressed, and the most prominent leaders of the movement arrested: they would remain in jail for the next few years.

One of BAJARAKA's leaders, Y Bih Aleo, later joined the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, more commonly known as the Viet Cong.

The FLHP

The early 1960s were to see increasing military activity in the Central Highlands; from 1961, American military advisers had assisted in setting up armed village defence militias (the Civilian Irregular Defense Groups, CIDG).

In 1963, after the 1963 South Vietnamese coup to overthrow Ngô Đình Diệm, all the leaders of BAJARAKA were released. In an effort to integrate Degar ambitions, several of them were given government posts: Paul Nur, vice-president of BAJARAKA, was appointed deputy provincial chief for the province of Kon Tum, while Y Bham Enuol, the movement's president, was appointed deputy provincial governor of Đắk Lắk Province. By March 1964, with US backing, the leaders of BAJARAKA, along with representatives of other ethnic groups and of the Upper Cham people, established the Central Highlands Liberation Front (French: Front de Liberation des Hauts Plateaux, FLHP).

The Front rapidly split into two factions. One faction, advocating peaceful means, was led by Y Bham Enuol. A second, led by Y Dhơn Adrong, advocated violent resistance. From March to May 1964, Adrong's faction infiltrated the border with Cambodia and set up at the old French base, Camp le Rolland, in Mondulkiri Province within 15 km of the Vietnamese border, where they continued to recruit FLHP fighters.

FULRO

.jpg)

In the meantime, the regional ambitions of Cambodian Head of State, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, had led to an effort to coordinate the operations of various separatist groups operating within South Vietnam and in the Cambodian border areas. Contact was made between Adrong's faction of the FLHP and two other groups:

- The Front for the Liberation of Champa (Front pour la Libération du Champa, FLC) led by Lieutenant-Colonel Les Kosem, a Cham officer in the Royal Cambodian Army (FARK).

- The Liberation Front of Kampuchea Krom (Front de Liberation du Kampuchea Krom, FLKK), representing the Khmer Krom of the Mekong Delta, led by former monk Chau Dara.

Kosem, the most senior Cham officer in the Cambodian army, had been involved in Cham activism since the late 1950s, and is suspected to have been working as a double agent for both the Cambodian secret service and the French.[3] The FLKK, on the other hand, originated in a semi-mystic, semi-military group known as the "White Scarves" (Kaingsaing Sar) based in the Seven Mountains area (Bảy Núi) of An Giang Province and founded in the late 1950s by a monk, Samouk Seng (or Samouk Sen); this had been supported by Sihanouk as a counterbalance to a republican guerrilla movement operating the same area, the Khmer Serei.[4] Chau Dara was also suspected to be working for the Cambodian secret service.[3]

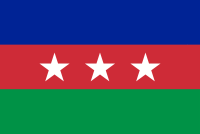

These contacts were to lead to the establishment of the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races (FULRO), based on the above groups and the FLHP. The flag of FULRO was designed with three stripes: one blue (representing the sea), red (a symbol of struggle) and green (the colour of the mountains). Three white stars on the central red stripe represented the three fronts of FULRO. A later form of the flag replaced the blue stripe with black.

The 1964 Buôn Ma Thuột rebellion

On September 20, 1964, there was an outbreak of violence by American-trained CIDG troops in the Special Forces bases of Buon Sar Pa and Bu Prang in Quang Duc province and in Buon Mi Ga, Ban Don and Buon Brieng in Darlac Province. Several Vietnamese soldiers were killed and the Americans disarmed, and FULRO activists from the Buon Sar Pa base seized the radio station on Route 14 on the south-west outskirts of Buôn Ma Thuột, from which they broadcast calls for independence. During the morning of September 21, Y-Bham Enuol was quickly abducted from his residence in Buôn Ma Thuột by elements from the Buon Sar Pa group and communiques were issued in his name.[5]

Outsiders advising and assisting the dissident Montagnard was Y-Dhon Adrong, an Ede (Rhade) ex-schoolteacher, two officers of the Royal Khmer Army, Lieutenant Colonel Y-Bun Sur, a member of the M'nong tribe and Province Chief of Cambodia's Mondulkiri Province, and Lieutenant Colonel Les Kosem, a Cham. Another adviser was Chau Dara, a Cham who was ex-monk from South Vietnam's Mekong Delta.[5]

On the evening of September 21, 1964, Brigadier General Nguyễn Huu Co, the commander of Military Region II, who had flown down to Buôn Ma Thuột from his headquarters in Pleiku, met with several rebel leaders From Buon Enao during which he assured them of his partial support of some of their demands in representations to Prime Minister General Nguyễn Khánh and the Saigon government. Following satisfactory negotiations, General Co requested that the rebel leaders brief the other dissident elements and ask them to peacefully return to their bases and await the outcome of the negotiations. The leaders who had met with General Co the previous night were prevented from briefing the Buon Sar Pa group which, still disgruntled, returned to their Buon Sar Pa Special Forces base, accompanied by Colonel John F. Freund, the US Army advisor to General Co. Colonel Freund's decision to accompany the still dissident Buon Sar Pa group was not authorised by General Co.[5]

The Buon Sar Pa group continued to defy the Vietnamese authorities and most of the CIDG force deserted their Buon Sar Pa base and moved, with their weapons and equipment across the international border and into Cambodia's Mondulkiri Province. Those CIDG troops remaining in the Buon Sar Pa base were threatened by General Co with a sharp military response and Colonel Freund, who had stayed with them, persuaded them to officially surrender to Prime Minister General Nguyễn Khánh. An official surrender ceremony took place in the mostly deserted Buon Sar Pa base however, this resulted in a loss of face for those dissident Montagnard who had agreed to stand down and await the promises made by General Co during negotiations with their leaders on the night of September 21, 1964.[5]

During the weeks that followed, the Buon Sar Pa CIDG deserters, in their base in Mundulkiri Province, were reinforced by a large number of deserters from the other Special Forces CIDG bases. Y-Bham was named head of FULRO and given the rank of general and named President of the High Plateau of Champa, a sign of the influence on the dissident Montagnard by the Cham advisers, Lieutenant Colonel Les Kosem and Chau Dara.[5]

Several weeks later, Y-Bham's family were quietly taken from his village, Buon Ea Bong, three kilometres north-west of Buôn Ma Thuột and escorted into the FULRO base in Cambodia's Mondulkiri Province.[5]

At the time of the Montagnard revolt, Lieutenant Colonel Y-Bun Sur and Lieutenant Colonel Les Kosem were senior officers serving in the Royal Khmer Army and both were also agents of Cambodia's Deuxiéme Bureau, that country's secret intelligence service. As well, Colonel Y-Bun Sur was still the Province Chief of Cambodia's Mondulkiri Province. This indicates the likely involvement of the government of Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Colonel Y-Bun Sur was also an agent in France's secret intelligence service at that time, the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (SDECE). This indicates possible involvement of the French in the revolt.[5]

The Americans were unsure who was ultimately responsible for the CIDG men's rebellion, and they initially blamed the Viet Cong and French.[3] However, the 'neutralist' Cambodian regime of Sihanouk had probably the greatest hand in events: 20 September 1964 'Declaration', by the Haut Comité of FULRO, contained anti-SEATO rhetoric that bore a strong resemblance to that issued by Sihanouk's regime in the same period.[6] Sihanouk hosted a conference, the "Indochinese People's Conference", in Phnom Penh in early 1965, at which Enuol headed a FULRO delegation.

Lack of progress in gaining concessions led to another FULRO uprising by its more militant faction in December 1965, in which 35 Vietnamese (including civilians) were killed. This event was rapidly suppressed, and four captured FULRO commanders (Nay Re, Ksor Bleo, R'Com Re and Ksor Boh) were publicly executed.

Negotiations and divisions

On June 2, 1967, Y Bham Enuol sent a delegation to Buôn Ma Thuột to petition the South Vietnamese government. On 25 and 26 June 1967, a congress of ethnic minorities throughout South Vietnam was convened to finalise a joint petition, and on August 29, 1967, a meeting was held under the direction of Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, President of the National Leadership Committee and Major General Nguyen Cao Ky, President of the Central Executive Committee. By December 11, 1968, negotiations between FULRO and the Vietnamese authorities had resulted in an agreement to recognise minority rights, establish a Ministry to support these rights, and to allow Y Bham Enuol to remain permanently in Vietnam.

However, some elements of FULRO, notably the FLC head Les Kosem, opposed the deal with the Vietnamese. On December 30, 1968, Kosem, at the head of several battalions of the Royal Cambodian Army, and accompanied by a group from the militant FULRO wing responsible for the 1965 fighting, surrounded and took Camp le Rolland. Enuol was placed under effective house arrest in Phnom Penh at the residence of Colonel Um Savuth of the Cambodian army, where he was to remain for the next six years.

On February 1, 1969, a final treaty was signed between Paul Nur, representing the Republic of Vietnam, and Y Dhơn Adrong. These events signified the end of FULRO as a 'political' movement, especially as its previous backer, the Sangkum regime of Sihanouk, was to fall to the Cambodian coup of 1970. However, some elements of FULRO, dissatisfied with the treaty, continued armed resistance in the Central Highlands. These disparate armed groups looked forward to the collapse of the Saigon regime, and had some local cooperation with the Viet Cong, who offered unofficial support such as caring for their wounded.[7]

After overthrowing pro-China Sihanouk, Cambodian leader Lon Nol, despite being anti-Communist and ostensibly in the "pro-American" camp, backed FULRO against all Vietnamese, both anti-communist South Vietnam and the Communist Viet Cong. Lon Nol planned a slaughter of all Vietnamese in Cambodia and a restoration of South Vietnam to a revived Champa state.

Vietnamese were slaughtered and dumped in the Mekong River at the hands of Lon Nol's anti-Communist forces.[8] The Khmer Rouge later imitated Lon Nol's actions.[9]

After the fall of South Vietnam

On April 17, 1975, the Cambodian Civil War ended when the Khmer Rouge communists – then in a political alliance with Sihanouk, the GRUNK – took Phnom Penh. General Y Bham Enuol, Lieutenant Colonel Y-Bun Sur, and some 150 members of the militant FULRO faction were, at the time, under house arrest in the compound of Colonel Um Savuth of the Khmer Army located near Pochentong Airport. They left the compound and sought refuge in the French Embassy. The Khmer Rouge forced the senior French diplomat to hand the group, men women and children, over to them. They were then marched to the Lambert Stadium then on the northern edge of Phnom Penh where they were executed by the Khmer Rouge along with many officials of the Cambodian regime; the remaining FULRO guerrillas in Vietnam, however, were to remain unaware of Enuol's death.

After the Fall of Saigon and the collapse of the South Vietnam government, it was suggested that the United States continue to support FULRO in its struggle against the government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Several thousand FULRO troops under Brigadier General Y-Ghok Niê Krieng carried on fighting Vietnamese forces, but the promised American aid did not materialise.

FULRO continued operations in the remote highlands throughout the late 1970s and into the early 1980s, but it was increasingly weakened by internal divisions, and trapped in an ongoing conflict between the Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese.[10] Despite this, in the early 1980s there was a peak in this second phase of the FULRO insurgency, possibly with active material support from China, who benefited from the conflict as part of its ongoing standoff with Vietnam.[11] Some estimates gave the total number of FULRO troops in this period at 7,000, mostly based in Mondulkiri, and supplied with Chinese armaments via the Khmer Rouge, which was by this point fighting its own guerrilla war in western Cambodia.[12] However, by 1986 this aid had ceased, a Khmer Rouge spokesman stating that while the tribesmen were "very, very brave", they had "no support from any leadership" and "no political vision".[12]

Following the cessation of supplies, the bitter guerrilla warfare would however in time reduce FULRO's forces to no more than a few hundred. In 1980 a unit of over 200 fighters was forced to split off and take refuge in Khmer Rouge on the Thai-Cambodian border. In 1985, 212 of these soldiers, under the command of Brigadier General Y-Ghok Niê Krieng and Pierre K'briuh, moved across Cambodia to the Thai border where Lieutenant General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, then Commander of the 2nd Royal Thai Army advised them that the Americans were no longer interested in fighting the Vietnamese. General Chavalit advised them to seek refugee status through UNHCR. Once this was granted they were moved to North Carolina in the U.S.[13]

In August 1992 journalist Nate Thayer traveled to Mondulkiri and visited the last FULRO base.[14] Thayer informed the group that FULRO's president Y Bham Enuol had been executed by the Khmer Rouge seventeen years previously. The FULRO troops surrendered their weapons in October 1992; many of this group were given asylum in the United States.[15] Even at this late stage, they only decided to give up armed struggle when they finally heard that Y Bham Enuol had been executed in April 1975.[12]

Combat history

Foundation

A settlement program of Kinh Vietnamese by the South Vietnamese government and united Vietnamese Communist government was implemented. The South Vietnamese and Communist Vietnamese settlement of the Central Highlands have been compared to the historic Nam tiến of previous Vietnamese rulers. During the Nam tiến (March to the South), Khmer and Cham territory was seized and militarily conquered (đồn điền) by the Vietnamese which was repeated by the state sponsored settlement of Northern Vietnamese Catholic refugees on Montagnard land by the South Vietnamese leader Diem and the introduction to the Central Highlands of "New Economic Zones" by the now Communist Vietnamese government.[16]

The Central Highlands Montagnards, Cham, and Delta Cambodians (Khmer Krom) were all alienated by the South Vietnamese government under Diem. The Montagnard Highlands were subjected to settlement with ethnic Vietnamese by Diem. A complete rejection of Vietnamese rule was felt by non-NLF tribes of the Montagnards in 1963.[17]

The Chinese, Khmer, and Chams were discriminated against by the South Vietnamese GVN, although the GVN treated Montagnards even worse than the three previous ethnicities, causing Montagnards to revolt again by going as far as to treat an entire Montagnard village as expendable pawn.[18] The South Vietnamese and the NLF (Viet Cong) assaulted the refugee camps inhabited by Montagnards in Dalat during the Tet offensive.[18] In the Central Highlands, Montagnard land was subjected to an attempted seizure by the South Vietnamese Madame Nguyễn Cao Kỳ in 1971.[19] 9 Montagnards and 3 Chinese were elected to South Vietnam's constitutional assembly after pressure was implemented on the government.[20]

Y'Bham brought FULRO to the fore in 1965 while anti-South Vietnamese propaganda was directed towards CIDG troops by FULRO leaflets attacking the Saigon regime and applauding Cambodia for its support since Prince Norodom Sihanouk launched the Indochinese People's conference in March 1963 with Y'Bham to shed light on the Montagnard situation.[21]

The Highlander leader Y Bham, Cham leader Les Kosem and Cambodian leader Sihanouk were all photographed together at the meeting where they declared their war against the South Vietnamese and America in the name of the Khmer, Cham, and highlander peoples.[22]

Y'Bham achieved control in 1965 and CIDG members were urged by FULRO to defect while the South Vietnamese authorities were attacked by FULRO which commended Cambodia under Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who promoted the "Indochinese People's Conference" at Phom Penh in 1963 which was attended by Y'Bham.[21]

Adjacent to Vietnam, the Cambodian forests were exploited as a base by FULRO fighters battling the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.[23][24][25]

The threatening secessionist group FULRO founded in the 1960s in South Vietnam by the tribes of the highland ethnic minorities.[26]

The FULRO Highlander, Khmer Krom, and Cham fighters were backed by Sihanouk against the South Vietnamese and challenged the Viet Cong for control calling the Americans as "imperialists" and launching an anti-South Vietnam uprising while at the same time viewing the Viet Cong as an enemy.[27]

The US Special Forces and Sihanouk backed the FULRO Montagnard fighters who were fighting against the South Vietnamese.[28]

The Montagnard inhabited Central Highlands became open to the Vietnamese only under French rule. The word savage (moi) was used by the Vietnamese against the Montagnard Degars. Both the South Vietnamese and the united Communist Vietnam government were fought against by the FULRO Degar fighters for the sake of the Central Highlands and Montagnard people under the direction of Y-Bham Enuol. The war lead to the deaths of 200,000 Degar people. Degar courts were abolished by South Vietnam and the Central Highlands became flooded with Vietnamese settlers under the direction of South Vietnam. Torture and mass arrests by the Vietnamese military were used in the CEntral Highlands against the Degar during the February 2001 protests against Vietnamese oppression.[29]

A report on Vietnamese oppression of Montagnards was issued by Human Rights Watch titled "Repression of Montagnards: Conflicts Over Land and Religion in Vietnam's Central Highlands".[30]

The lowlander Vietnamese seized Montagnard lands, attacked their culture and language, and masscred the Monyagnards due to their hatred against them and their distinct religion, culture, language, and ethnicity (Malayo-Polynesian) marks them apart to the Vietnamese. They were referred to as savage "moi" by the Vietnamese. The Vietnamese persecuted them for hundreds of years.[31]

They were excellent at trailing and hunting targets. It was under French rule when the highlands were first subjected to Vietnamese settlement. Prior to the division the earlier unified Vietnam had abused and mistreated the Montagnards so South Vietnamese and North Vietnamese alike were targeted and hated by the Montagnards during the war due to the discrimination and racism against the Montagnards at the hands of the Vietnamese.[32]

Uprising during the Republic of Vietnam

In 1958 the Central Highlands was a scene of a revolt by the native tribals against assimilation and settlement of the land by the Vietnamese implemented by the South Vietnamese government. Neither the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) nor South Vietnamese were on the side of FULRO which Prince Sihanouk supported after its founding in 1964 from a union of multiple highlander tribals. The war led to the deaths of a massive amount of the tribal natives due to the fighting which went on throughout the highlands.[33]

The new changes to the economy and living in the Central Highlands provoked the tribals to started FULRO to resist the South Vietnamese with the aid of Sihanouk.[34]

Y'Bham Enuol established FULRO whose sole common bond and ideology was anti-Vietnamese sentiment, with questionable allegiance to anything else, created in 1964, based in Ratanakiri and Mondolkiri provinces in Cambodia and the Central Highlands in Vietnam of the local mountaineers.[35]

The Viet Cong and Cambodia approached FULRO after its foundation.[36]

The Cambodian Prince Sihanouk backed the creation of FULRO which was formed out of a united alliance of South Vietnam's different hill tribal peoples.[37]

The South Vietnamese oppression of the highlanders caused the creation of FULRO and it operated from Cambodia with support by Sihanouk in order to resist the oppression, two provincial capitals were seized by FULRO in December 1965 and FULRO forced the South Vietnam to grant concessions.[28]

There was long-established animosity between the mountain tribesman and lowland Vietnamese. Montagnards fought against South Vietnamese soldiers in Pleiku, Darlac, and Quang Quc. The Tribal mountain peoples united in FULRO launched uprisings in Darlac, Lac Thin. Phu Tien came under Montagnard rule after they inflicted heavy losses on South Vietnamese soldiers, rising in rebellion in Phu Bon and battling South Vietnamese soldiers.[38]

Representation and an autonomous political entity were among the dictations stated as their goals by FULRO against South Vietnam.[39]

During the uprising, anti-government Montagnard Rhade insurgents from CIDG slaughtered South Vietnamese troops and seized American soldiers as prisoners, after the uprising some of the Montagnards joined the Montagnard separatist movement FULRO led by Y-Bham Enuol in Cambodia. The Montagnards received Prince Sihanouk and Cham support and were not connected to the Viet Cong.[40]

The instigation for the uprising is believed in some quarters to have originated from Cambodia (Phnom Penh) where tribal heads against the Vietnamese had congregated before the FULRO uprising on September 20 at Ban-Me-Thuot.[41]

The state goal was "liberation" from oppression suffered by minorities at the hands of South Vietnam and the Montagnards, Chams, and Khmers were all asserted to be spoken for by FULRO.[42]

The South Vietnamse government in Saigon sent a diplomatic contingent in August 1968 to Ban Me Thuot to negotiate with FULRO representatives including Y Bham Enuol after a promise of safe conduct was given to him by Tran Van Huong, the Prime Minister of South Vietnam, after FULRO members at Camp Le Rolland agreed to negotiate since South Vietnam was no longer the top priority for Cambodia because the Khmer Rouge was starting to distract Sihanouk in 1968.[43]

Montagnard women were abused (tortured) at the hands of Vietcong forces.[44][45][46]

The Cambodian Cham Les Kosem, a Lieutenant Colonel, was responsible for matters relating to ethnic minorities under Sihanouk and both Kosem and Sihanouk were aware of FULRO.[43]

The three stripes on the flag of FULRO represented the unification of the "Struggle Front of the Khmer of Lower Cambodia", the "Front for the Liberation of Champa", and "Bajarka Movement" after Y-Dhon Adrong was convinced to join them together by Cham leader Les Kosem during the Montagnard uprising against South Vietnam.[47]

While in Cambodia at FULRO headquarters, Y-Bham had his family moved into Mondul Kiri's Krechea via Vietnam's Darlac and Ban Don areas.

The South Vietnamese Truong Son was commanded by Barry Peterson and Peterson was furious when Y-Preh, a FULRO member wanted to meet him since contact was prohibited with the insurgents who were fighting against South Vietnam.

After the Montagnard uprising against South Vietnam, 10 months passed before FULRO agreed to negotiate with South Vietnam.[47]

After Colonel Freund agreed to capitulate and turn over a base to the South Vietnamese, the Montagnards in the Buon Sarpa unit were greatly displeased and discontent. In Mondul Kiri forests, Sihanouk's Cambodia Royal Khmer Army officers Um Savuth and Cham Les Kosem discussed with Bajaraka Montagnard members where Les Kosem initiated the amalgamation and foundation of FULRO.[47]

The 1950s BAJARKA movement came before FULRO which was its successor.[48]

An uprising against the South Vietnamese was planned with the cooperation of Front for the Liberation of Champa, Struggle Front of the Khmer of Lower Cambodia and a Rhade official.

While the Bajaraka movement founded, it is believed that parallel to it the establishment of the "Front for the Liberation of Champa" took place.

FULRO documents contained the signatures of and FULRO meetings were attended by members of Front for the Liberation of Champa. A Cham goddess's name was used as a call sign by Les Kosem.[49]

The FULRO organizations was backed by Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia, anti-Vietnamese and anti-American Frenchmen, and it was attempted to be used against the Vietcong's NFL by the Americans due to their animosity towards Vietnamese.[50]

The Front de libération du Kampuchea Nord, the Front de libération du Kampuchea Krom, the Front de libération du Champa formed FULRO in 1964 after the Khmer Krom, the PMS minorities (Montagnards), and both Vietnam Cham and Cambodian joined in unity together to fight the Vietnamese.

The 5th BIs Special Infantry Brigade Fr: Brigade d'Infanterie Spéciale, was made out of Cham Muslims and Malay Muslims- by some ex-FULRO South Vietnam Phanrang and Phanri born Cham, and "Khmer Islam" (Cambodian Cham Muslims and Malays) under the rule of Lon Nol and minority affairs in Cambodia were delegated to the Cham Les Kosem.[51]

The 1960s separatist organizations in South Vietnam were joined in a coalition called FULRO which included under the direction of Cambodian Cham Les Kosem, the "Front for the Liberation of Champa" which was founded in 1962 by Cham in Vietnam. The Central Highlands were the scene of ethnic minorities forming separatist movements.[52]

In 1963 the "Mouvement Khmer-Serei" was started against the Saigon government by Norodom Sihanouk's government.

The Malayo-Polynésian and Mon-Khmer ethnic minorities who were against the South Vietnamese Saigon government joined together in September 1964 such as the Cambodian government support "Front de Libération du Champa".

The separatist movements were encouraged to seek independence as the Khmer government backed FULRO at the Indochinese People's conference.[53]

The Front de Libération du Champa flag included a Crescent star.[54][55]

Lon Nol backed FULRO hill tribes, and in South Vietnam and Cambodia's frontier region he fought a proxy war against the NLF via Khmer Krom detachments as he desired to emulate Van Pao.[56]

The settlement of ethnic Vietnamese from densely populated areas to relieve the financial pressure on those areas on the lands of the tribals in the Central Highlands was sponsored by the Vietnamese government and it led to the creation of FULRO to resist the Vietnamese.[57]

A "liberated area" served as the base for the chiefs of FULRO, making their goals unclear, being an organization founded by Montagnards, Cham, and Khmer Krom and mounted an uprising against South Vietnam as they operated in Cambodia near Darlac in the Central Highlands.[58]

Kuno Knöbl tried to discuss FULRO with the Pleiku-based Special Forces Captain Schwikar who refused to talk about it.[59]

The Vietnamese Communists used airplanes to bomb FULRO fighters as they revolted against the "re-education", economic policies and other policies which affected their way of life which were implemented by the Vietnamese Communists. With Cambodian backing, Montagnard FULRO fighters fought against the Vietnamese Communist government of unified Vietnam until 1992.[16]

Vietnamese settlement

A settlement program of Kinh Vietnamese by the South Vietnamese government and united Vietnamese Communist government was implemented. Leaving out any plans for autonomy for ethnic minorities, an assimilation plan was launched by the South Vietnamese government with the creation of the "Social and Economic Council for the Southern Highlander Country", the South Vietnamese based their approach to the highlanders by claiming that they would be "developed" since they were "poor" and "ignorant", making swidden agriculturalists sedentarize and settling ethnic Vietnamese from the coastal regions into the highlands such as Northern Vietnamese Catholic refugees who fled to South Vietnam, 50,000 Vietnamese settlers were in the highlands in 1960 and in 1963 the total number of settlers was 200,000 and up to 1974 the South Vietnamese were still implemented the settlement plan even though the highland natives experienced massive turbulence and disorder because of the settlement, and by 1971 less than half of a scheme back by the Americans to leave Montagnards with just 20% of the Central Highlands was completed, and even in the parts of the highlands which did not experience settlement, the South Vietnamese threw the native tribes into "strategic hamelets" to keep them away from places where communists potentially operated and the South Vietnamese consistently spurned any attempts too make overtures to the native Highlanders.[60][61][62]

The South Vietnamese government made only symbolic, useless concessions to ethnic minorities in order to stop FULRo from gaining support.[63][64][65]

FULRO tribals rose up in an uprising against Diem's settlement of the Highlands with ethnic Vietnamese settlers.[66]

In 1955 the Central Highlands were flooded with Northern Vietnamese migrants after the autonomous Montagnard area was abolished by Ngô Đình Diệm. Y Bham Enoul founded Bajaraka on January 5, 1958, to resist the discrimination, Vietnamese settlement on Highlands and forced assimilation by the South Vietnamese government. The United Nations Secretary General and foreign embassies were contacted by Y Bham Enuol. "Front for the Liberation of the Highlands of Champa" (Mặt Trận Giải Phóng Cao Nguyên Champa) and Bajaraka were both headed by Y Bham Enuol. He was killed by the Khmer Rouge on April 20, 1975. Les Kosem, Y Bham Enuol and Prince Norodom Sihanouk worked together to found FULRO and launch an uprising against the South Vietnamese government to regain their land from the Vietnamese settlers. Vietnam is still persecuting the religion and culture of the natives who live in poverty and are losing their land to ethnic Vietnamese settlers who continue to flood into their land in the Central Highlands in Vietnam today.[67]

An uprising against South Vietnam was launched by Bajaraka head Y Bham Enoul with Montagnard Monong and Rhade soldiers who seized American Special Forces and some Vietnamese as prisoners in their CIDG bases after seizing a Ban Me Thuot based radio station and inflicting 70 deaths upon the Vietnamese when taking over Darlac CIDG bases with 3,000 troops on September 19, 1964. Prince Sihanouk's administration in Cambodia guided FULRO with anti-SEATO, anti-American ideology and in 1965 FULRO released maps showing that their ultimate goal was for Montagnard and Cham independence within a revived new Champa state and for Khmers to retake Cochinchina, corroborating the statement Notre but est de défendre notre survie et notre patrimoine culturel, spirituel et racial, et ainsi l'Indépendence de nos Pays. which was found in their declaration which also claimed that ethnic minorities were being subjected to genocide at the hands of the South Vietnamese, calling for the Montagnards, Khmer Krom and Cham to unity in FULRO under the direction of their Haut Comité on September 20, 1964. CIDG bases were where the rank and file were found while it was in Cambodia where the chiefs of FULRO were based and from where the FULRO Montagnard, Cham, and Khmer Krom chiefs directed the uprising.[58][68]

Concessions for ethnic minority rights were issued after the South Vietnamese government was forced by the FULRO insurgency to address the problem under "Front for the Liberation of the Highlands of Champa" (Mặt Trận Giải Phóng Cao Nguyên Champa) and FULRO led by Les Kosem and with the help of the intelligence agency and military of Cambodia under Prince Norodom Sinhaouk. The effort to free the Cham people was led by Major General Les Kosem. The Cham people keep the soul of FULRO alive according to former FULRO Cham member Po Dharma who went a journey to see Les Kosem's grave.[69]

Quang Van Du was the legal registered name of the Cham Po Dharma. He stood against ethnic Kinh Vietnamese bullies for his fellow Cham while he was in school and helped spread Cham nationalist ideas against the South Vietnamese. He became a member of FULRO and attended a FULRO training camp in Cambodia and fought in Mondulkiri. While in Cambodia he attacked the North Vietnamese and South Vietnamese embassies and then he fought against Vietnamese Communists. After being wounded in battle he quit his military career after seeking the permission of Les Kosem himself and went to France to be educated and serve FULRO in a civilian capacity.[70]

A settlement program of indigenous people's land in the Central Highlands with Vietnamese soldiers and settlers was implemented by South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem starting in 1955. The Highlander Liberation Front was founded in 1955 during a meeting of indigenous highlands who had originally rallied to the Rade Y Thih Eban against the South Vietnamese government. In 1960 in Phnom Penh the foundation of the Les Kosem led "Champa Liberation Front" and "Kampuchia Krom Liberation Front" happened to fight against South Vietnamese settlement.[71]

FULRO tried to create a sovereign and self-governing Central Highlands through insurgency against the South Vietnamese for a decade while based in Cambodia's Mondulkiri province with support from Prime Minister Lon Nol of Cambodia, led by Cham Lieutenant Major Les Kosem and Rhade leader Y Bham Enuol but when the Khmer Rouge came to power, they attacked FULRO. Les Kosem fled the country while the French embassy sheltered other fULRO leaders, however diplomatic immunity was violated when the FULRO leaders were seized and killed by the Khmer Rouge after storming the embassy. The North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge effectively ended FULRO however elements of FULRO still survived and decided to wage war against the new Communist Vietnamese government of unified Vietnam as they had against the South Vietnamese. FULRO received support from China and Cambodian elements against Vietnam. The Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia was fought against by Dega FULRO remnants.[72][73]

During the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

All forms of Vietnamese domination were opposed by FULRO tribesman in the Central Highlands and they continued the fight against the united Vietnamese Communist government after the fall of South Vietnam.[74][75]

In the novel For the Sake of All Living Things it was noted that both anti-Communist and Communist, Vietnamese in general were fought against by the FULRO mountaineers in the highlands.[76]

Y Bham Enuol, the chief of FULRO along with 150 other members hid in the French embassy when the Khmer Rouge took over Phnom Penh, however the Khmer Rouge forced the French consul to surrender them all to their custody and had them killed.[27]

The anti South Vietnam, and anti Communist Vietnam FULRO which fought both the South Vietnamese and the Communist Vietnamese, was given aid and assistance by China via Thailand to fight against the Vietnamese throughout the 1970s and 1980s while China also backed ethnic minorities in northern Vietnam along the border against the Vietnamese.[77]

China backed the Central Highlands-based FULRO Koho, Rhade, Jarai, and Bahnar fighters to battle the Vietnamese PAVN in the provinces of Dac Lac, Kontum, and Gai Lai where Vietnamese military and police stations were assaulted by the fighters.[78]

China, North Vietnam ethnic minorities, the FULRO Montagnards, right wing Laotians, Prince Sihanouk, right wing Cambodians under Son Sann, and the Thai were all anti-Communist groups contacted by Truong Nhu Tang who was a member of the Committee for National Salvation which was against the Communist Vietnamese government.[79][80]

The FULRO Montagnard fighters received military materials from China in 1980.[81]

The Trotskyist Fourth International (post-reunification) run Inprecor and Intercontinental Press claimed that the CIA and French were the ones who started FULRO as it attacked Prince Sihanouk and China for their efforts to support FULRO against Vietnam.[82]

Anti-Vietnamese Laotian organizations and FULRO along with Cambodian (Khmer) organizations were backed by China.[83]

The culture of the Montagnards was targeted for extermination by the Vietnamese and there were centuries of warfare between the Vietnamese and Montagnards. Assault rifles, carbines, rockets, grenades, and ammunition were among the weapons the remaining Montagnard FULRO fighters had in their possession when they gave up the struggle and turned them over to the United Nations in 1992.[84][85]

FULRO fighters in the jungles of Mondulkiri who were fighting against the Vietnamese were interviewed in 1992 by Nate Thayer.[86]

Other minority resistance groups

The Montagnards in FULRO fought the Vietnamese for twenty years after the end of the Vietnam War and the scale of Vietnamese attacks on the Montagnards reached genocidal proportions with the slaughter of over 200,000 Montagnards after 1975. The Vietnamese slaughtered 200,000 Montagnards after 1975 during the war between FULRO and Vietnam in the Central Highlands, as the Vietnamese lease land for Japanese companies to harvest lumber in the area. Munitions, weapons, and 5,000 rifles were given by the Chinese to the Montagnards after the Montagnards requested help from China via Thai General Savit-Yun K-Yut since the United States refused to help the FULRO Montagnards against the Vietnamese.[87]

FULRO was backed by China. The fierce insurgency against the Vietnamese Communist government of unified Vietnam by FULRO involved 12,000 fighters in the Central Highlands. Vietnamese government workers were attacked in their offices and houses by guerilla detachments of FULRO fighters originating from Cambodia and mountain regions.[88][89]

The Central Highlands had a secret route via Cambodia to China where FULRO fighters were given Chinese aid and help through weapons and cash. In the provinces of Dac Lac, Kontum, and Gai Lai, Vietnamese garrisons of soldiers and police were assaulted by the Koho, Rhade, Jarai, and Bahnar FULRO fighters.[78]

Anti North-Vietnam Laotian Hmong rebels and the anti-South Vietnamese FULRO both received support from China and Thailand to fight against the Communist government of unified Vietnam.[77]

There was high mobility among ethnic minorities like the Hmong, Yao, Nung, and Tai across the border between China and Vietnam.[90]

At the Laotian border Hmong insurgents backed by China fought. After the United States stopped aiding the Hmong, the Chinese assistance was sought by the Hmong fighters.[91]

In Phong Saly province of Laos, Meo (Hmong) fighters were backed by the Chinese against the Laotian government which was an ally of Vietnam.[92]

Zao, Lu, and Khmu ethnic minorities were also backed in Phou Bia against the Vietnamese by China.[93]

The Vietnamese executed any members of its ethnic minorities along the border with China who worked for the Chinese.[77][94][95]

Aid and assistance came from China via Kunming in Yunnan to anti-Vietnamese organizations in Laos, Cambodia (Kampuchea) and FULRO in Vietnam to form a united coalition against Vietnam.[96]

In the northeast area of Cambodia raids were conducted by combined FULRO forces and Cambodian guerillas fighting against Vietnam from Preah Vihear.[97]

Laos and Cambodia (Kampuchea) based anti-Vietnamese organizations were conduits of support from China to a FULRO like group which was founded and made out of "hill peoples" from Laos and Cambodia.[98]

Laotian and Cambodian organizations fighting against the Vietnamese were a transit point via which Chinese support reached FULRO like organizations.[98]

Post-Insurgency

A 2002 article in the Washington Times reported that Montagnard women were subjected to forced mass sterilization by the Vietnamese government for the Montagnard's population to be reduced, in addition to stealing lands of the Montagnards, and attacking their religious beliefs, killing and tortuting them in a form of "creeping genocide",[99]

Luke Simpkins, an MP in the House of Representatives of Australia condemned the Vietnamese persecution of the Central Highland Montagnards and noting both the South Vietnamese government and regime of unified Communist Vietnam attacked the Montagnards and conquered their lands, mentioning FULRO which fought against the Vietnamese and the desire for the Montagnards to preserve their culture and language. The Vietnamse government has non-Montagnards settle on Montagnard land and killed Montagnards after jailing them. There were 200,000 Montagnard deaths to the war.[100]

Former Green Beret and writer Don Bendell wrote a novel based on Vietnam's policies in the Central Highlands with details in his book such as accusing the Communist Vietnamese government implemented a genocidal and discriminatory policy against the native Montagnards in the Central Highlands, banning Montagnard languages and implementing Vietnamese language, having Vietnamese men marry Montagnard girls and women by force, colonizing the Central Highlands with massive amounts of Vietnamese settlers form the lowlands, inflicting terror and on the Montagnards with police force, and making them perform slave labor, erecting plantations for rubber, tea, and coffee on the Central Highlands after destroying the vegetation in the area and due to these "apartheid-like conditions".[101]

Khmer Krom

Cambodia used to formerly own Kampuchea Krom whose indigenous inhabitants were ethnic Cambodian Khmers before the settling Vietnamese entered via Champa. The entity of Vietnam under colonial French rule received the Khmer lands of Kampuchea Krom from France on 4 June 1949. Vietnam oppresses the Khmer Krom and the separatists among the Khmer Krom consider Vietnamese control as colonial rule. The Vietnamese gave new Vietnamese names to the Kampuchea Krom provinces they gradually seized.[102][103][104]

Seizure of land and persecution of Khmer Krom Buddhist Monks by the Vietnamese were issues brought up during a resolution against Vietnam passed by the European Parliament by Khmer Krom protestors.[105]

Khmer Krom still bitterly recall the day that the Vietnamese received the 21 provinces of Kampuchea Krom from the French on 4 June 1949. The Cambodian Kampuchea Krom were the natives of the region and were not consulted on the decision made to give the land to the Vietnamese by the French. The Vietnamese suppressed the Khmer script and Khmer language, attacking the culture, religion and books of the Khmer Krom. People who demonstrated against land seizures by the Vietnamese were jailed by the Vietnamese Communists. Khmer nationalism is a strong impediment to the destruction of Khmer Krom identity by the Vietnamese. The Vietnamese have jailed and killed Khmer Krom during the 64 years of rule after the French transfer.[106]

Chau Dara, a Buddhist monk, founded the Khmer Krom movement "Struggle Front of the Khmer of Kampuchea Krom" in response to policies of the South Vietnamese government like having Khmer Krom land in the Mekong Delta conquered by Vietnamese Kinh, anti-Buddhist policy and forced assimilation into Vietnamese culture. FULRo was created by the unification of Montagnard Bajaraka with the "Struggle Front of the Khmer of Kampuchea Krom" and "Front for the Liberation of Champa" in 1964. Anti-Khmer Krom policies are implemented by the Vietnamese government because of Khmer Krom separatism.[107]

References

- Written by BBT Champaka.info (8 September 2013). "Tiểu sử Ts. Po Dharma, tác giả Lịch Sử 33 Năm Cuối Cùng Champa". Champaka.info. Champaka.info.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- White, T. Swords of lightning: special forces and the changing face of warfare, Brassey's, 1992, p.143

- Dommen, A. J. The Indochinese experience of the French and the Americans, Indiana University Press, 2001, p.615. The Kaingsaing Sar were similar to the Hòa Hảo, in that they evolved from a religious group to an armed nationalist one.

- "Tiger Men: An Australian Soldier's Secret War in Vietnam" by Barry Petersen.

- Christie, C. J. A modern history of Southeast Asia: decolonization, nationalism and separatism, I B Tauris, 1996, p.101

- Fenton, J. All the Wrong Places, Granta, 2005, p.62

- Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 548–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 554–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- Whereas the Vietnamese government still maintains FULRO negotiated an uneasy allicance with the Khmer Rouge in this period, pro-Montagnard groups state that men were in fact kidnapped by the Khmer Rouge to serve as porters and clear minefields

- O'Dowd, E. C. Chinese military strategy in the third Indochina war: the last Maoist war, Routledge, 2007, p.97

- Jones, S. et al, Repression of Montagnards, Human Rights Watch, p.27

- Nate Thayer, "Forgotten Army: The Rebels Time Forgot", Far Eastern Economic Review, September 10, 1992, pp. 16-22.

- Nate Thayer, "Montagnard Army Seeks UN Help. Phnom Penh Post, September 12, 1992.

- Nate Thayer and Leo Dobbs, "Tribal Fighters Head for Refuge in USA. Phnom Penh Post, October 23, 1992.

- Oscar Salemink (2003). The Ethnography of Vietnam's Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850-1990. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2579-9.

- Frances FitzGerald (30 May 2009). Fire in the Lake. Little, Brown. pp. 298–. ISBN 978-0-316-07464-3.

- Frances FitzGerald (1989). Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. Vintage Books. pp. 298 389 489. ISBN 978-0-679-72394-3.

- Frances FitzGerald (1989). Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. Vintage Books. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-679-72394-3.

- Frances FitzGerald (1989). Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. Vintage Books. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-679-72394-3.

- John Prados (1995). The Hidden History of the Vietnam War. I.R. Dee. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-56663-079-5.

- Gerald Cannon Hickey (2002). Window on a War: An Anthropologist in the Vietnam Conflict. Texas Tech University Press. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-0-89672-490-7.

- Daljit Singh; Anthony L Smith (January 2002). Southeast Asian Affairs 2002. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 351–. ISBN 978-981-230-162-8.

Sihanouk FULRO.

- Daljit Singh; Anthony L Smith (January 2002). Southeast Asian Affairs 2002. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 351–. ISBN 978-981-230-162-8.

- Daljit Singh; Anthony L. Smith (6 June 2002). Southeast Asian Affairs 2002. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 351–. ISBN 978-981-230-160-4.

- Milton J. Rosenberg (1 January 1972). Beyond Conflict and Containment: Critical Studies of Military and Foreign Policy. Transaction Publishers. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-1-4128-1805-6.

- Arthur J. Dommen (20 February 2002). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Indiana University Press. pp. 650–. ISBN 0-253-10925-6.

- George McT. Kahin (2 September 2003). Southeast Asia: A Testament. Routledge. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-1-134-42311-8.

- "Degar-Montagnards". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: UNPO. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: UNPO. March 25, 2008.

- Human Rights Watch (Organization) (2002). Repression of Montagnards: Conflicts Over Land and Religion in Vietnam's Central Highlands. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-272-2.

- Hans Halberstadt (12 November 2004). War Stories of the Green Berets. Voyageur Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-7603-1974-1.

- A.T. Lawrence (15 September 2009). Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant. McFarland. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-7864-5470-9.

- Charles F. Keyes (1977). The Golden Peninsula: Culture and Adaptation in Mainland Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-8248-1696-4.

- Contemporary Southeast Asia. Singapore University Press. 1989. p. 218.

- Wilfred P. Deac (1997). Road to the Killing Fields: The Cambodian War of 1970-1975. Texas A&M University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-58544-054-2.

- American University (Washington, D.C.). Foreign Area Studies (1968). Area handbook for Cambodia. For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 185.

- Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Center of International Studies; American Anthropological Association (1967). Southeast Asian tribes, minorities, and nations. Princeton University Press. p. 25.

- Reedy, Thomas A. (December 18, 1965). "Americans in Saigon Placed Under Curfew". The Owosso Argus-Press (297). Owosso, Michigan. Associated Press. p. 1.

- Reedy, Thomas A. (Dec 18, 1965). "Saigon Curfew Ordered". The Evening News. Newburgh, N.Y. Associated Press. p. 7A.

- Frank Walker (1 November 2010). The Tiger Man of Vietnam. Hachette Australia. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-7336-2577-0.

- Ralph Bernard Smith (1983). An International History of the Vietnam War: The struggle for South-East Asia, 1961-65. Macmillan. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-333-33957-2.

- Harvey Henry Smith; American University (Washington, D.C.). Foreign Areas Studies Division (1967). Area handbook for South Vietnam. For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 245.

- Arthur J. Dommen (2001). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Indiana University Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-253-33854-9.

- "Weaker Sex Plays Strong Vietnam Role". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Saigon, South Vietnam‒AP‒ Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States. August 28, 1965. p. Page 2, Part 1.

- "Women Deeply Involved In Viet Nam War". Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal. XL (206). Daytona Beach, Florida. Associated Press. 1965-08-28. p. 1.

- "Women Deeply Involved In Viet Nam War". Daytona Beach Sunday News-Journal. XL (206). Daytona Beach, Florida. Associated Press. 1965-08-28. p. 1.

- Barry Petersen (1994). Tiger Men: A Young Australian Soldier Among the Rhade Montagnard of Vietnam. White Orchid Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-974-89212-5-9.

- Gerald Cannon Hickey (1970). Accommodation and coalition in South Vietnam. Rand Corporation. p. 30.

- Gerald Cannon Hickey (1970). Accommodation and coalition in South Vietnam. Rand Corporation. pp. 24 29 30.

- Ben Kiernan (1986). Burchett: Reporting the Other Side of the World, 1939-1983. Quartet Books, Limited. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-7043-2580-7.

- Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. The Branch. 2001. pp. 12, 13.

- Greg Fealy (31 May 2006). Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia: a contemporary sourcebook. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 34. ISBN 978-981-230-368-4.

- Etudes khmères. CEDORECK. 1980. pp. 176 177 178.

- "HLAGRU – FULRO". HLAPŎK ÐÊGAR Asăp blŭ klă sit kơ djuê ana Ðêgar!. HLAPŎK ÐÊGAR Asăp blŭ klă sit kơ djuê ana Ðêgar!. Archived from the original on 2006.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__pgi-4q2Sc

- Malcolm Caldwell; Lek Tan (1973). Cambodia in the Southeast Asian war. Monthly Review Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-85345-171-6.

- Contemporary Southeast Asia. Singapore University Press. 1989. p. 218.

- Clive J. Christie (1996). A modern history of Southeast Asia: decolonization, nationalism and separatism. Tauris Academic Studies. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-85043-997-4.

- Kuno Knöbl (1967). Victor Charlie: the face of war in Viet-Nam. Praeger. p. 179.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2008). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. NUS Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-9971-69-418-0.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2004). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Cornell University Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 0-8014-4175-7.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2004). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Cornell University Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 0-8014-8930-X.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2008). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. NUS Press. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-9971-69-418-0.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2004). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Cornell University Press. pp. 194–. ISBN 0-8014-4175-7.

- Christopher R. Duncan (2004). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Cornell University Press. pp. 194–. ISBN 0-8014-8930-X.

- "The Realities of Vietnam" (PDF). The Ripon Forum. The Ripon Society. III (9): 21. 1967. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Written by Ja Karo, độc giả trong nước (18 April 2013). "Kỷ niệm 38 năm từ trần của Y Bham Enuol, lãnh tụ phong trào Fulro". Champaka.info. Champaka.info.

- Clive J. Christie (15 February 1998). A Modern History of Southeast Asia: Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism. I.B.Tauris. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-86064-354-5.

- Written by BBT Champaka.info (24 April 2013). "Viếng thăm mộ Thiếu Tướng Les Kosem, sáng lập viên phong trào Fulro". Champaka.info. Champaka.info.

- Written by BBT Champaka.info (8 September 2013). "Tiểu sử Ts. Po Dharma, tác giả Lịch Sử 33 Năm Cuối Cùng Champa". Champaka.info. Champaka.info.

- Dr. Po Dharma. "From the F.L.M to Fulro (1955-1975)". Cham Today. Translated by Musa Porome. IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 2006.

- Dominique Nguyen (6 June 2013). "Post-FULRO Events (1975-2004)". Cham Today. Translated by Sean Tu. IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 2006.

- Dominique Nguyen. "Post-FULRO Events (1975-2004)". Cham Today. Translated by Sean Tu. IOC-Champa. Archived from the original on 2006.

- DAWSON, ALAN (April 12, 1976). "New Communist governments feeling some opposition". The Dispatch. Lexington, N.C. p. 20.

- DAWSON, ALAN (April 4, 1976). "Resistance To Communists Grows In Indochina". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. newspaper located at (Sarasota, Florida) author reported from (Bangkok, Thailand (UPI)). p. 12·F.

- John M. Del Vecchio (26 February 2013). For the Sake of All Living Things: A Novel. Warriors Publishing Group. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-4804-0189-1.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Mother Jones (1983). Mother Jones Magazine. Mother Jones. pp. 20–21. ISSN 0362-8841.

- Mother Jones. Foundation for National Progress. 1983. p. 20.

- Contemporary Southeast Asia. Singapore University Press. 1989. p. 218.

- Intercontinental Press Combined with Inprecor. Intercontinental Press. 1981. p. 235.

- Far Eastern Economic Review. July 1981. p. 15.

- "Guerrillas cease struggle after 28 years". Lawrence Journal-World. 134 (285). Lawrence, Kansas. Associated Press. Oct 11, 1992. p. 14A.

- "Rebels end 28-year struggle". Rome News-Tribune. 149 (242). Rome, Georgia. Associated Press. Oct 11, 1992. p. 8A.

- Thayer, Nate (25 September 1992). "Lighting the darkness: FULRO's jungle Christians". The Phnom Penh Post.

- George Dooley (18 December 2007). Battle for the Central Highlands: A Special Forces Story. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-307-41463-2.

- Carlyle A. Thayer (1994). The Vietnam People's Army Under Đổi Mới. Regional Strategic Studies Programme, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-981-3016-80-4.

- Carlyle A Thayer (1994). The Vietnam People's Army Under Dỏ̂i Mơoi. Regional Strategic Studies Programme, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-981-3016-80-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-1-134-12268-4.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Taylor & Francis. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-203-08896-8.

- Edward C. O'Dowd (16 April 2007). Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War: The Last Maoist War. Routledge. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-134-12267-7.

- Jonathan Luxmoore (1983). Vietnam: The Dilemmas of Reconstruction. Institute for the Study of Conflict. p. 20.

- Asian Almanac: Weekly Abstract of Asian Affairs. V.T. Sambandan. 1985.

- K. K. Nair (1 January 1984). ASEAN-Indochina relations since 1975: the politics of accommodation. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. p. 181.

- Johnson, Scott (2002-04-07). "Creeping Genocide in Asia: Vietnam". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 2006.

- "Australia MP Luke Simpkins Speaks Out On Persecution of Montagnards". Montagnard Foundation. Commonwealth of Australia – Vietnam: Montagnard's Speech Wednesday, 6 July 2011 By Authority of the House of Representatives. July 8, 2011. Archived from the original on 2006.

- Don Bendell (2 October 2007). Criminal Investigation Detachment #3: Bamboo Battleground. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-425-21631-6.

- "Map of Kampuchea Krom". Khmer Krom Community. Khmer Krom Community. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013.

- "Map of Kampuchea Krom". Khmer Krom Community. Khmer Krom Community.

- "Map of Kampuchea Krom". Khmer Krom Community. Khmer Krom Community. October 15, 2015.

- Vien Thatch (November 4, 2008). "Khmer Krom: Demonstration at European Parliament". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: UNPO. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: UNPO.

- Pech Sotheary (4 June 2013). "The 64rd Anniversary of losing Kampuchea Krom territorial integrity to Vietnam". Voice of Democracy (VOD – ព័ត៌មានឯករាជ្យនៅកម្ពុជា). Translated by Tat Oudom. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013.

- On the Margins: Rights Abuses of Ethnic Khmer in Vietnam's Mekong Delta. Human Rights Watch. 1 January 2009. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-56432-426-9.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FULRO. |