Australian Air Corps

The Australian Air Corps (AAC) was a temporary formation of the Australian military that existed in the interval between the disbandment of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) of World War I and the establishment of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in March 1921. Raised in January 1920, the AAC was commanded by Major William Anderson, a former AFC pilot. Many of the AAC's members were also from the AFC and would go on to join the RAAF. Although part of the Australian Army, for most of its existence the AAC was overseen by a board of senior officers that included members of the Royal Australian Navy.

| Australian Air Corps | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1920–21 |

| Country | Australia |

| Branch | Australian Army |

| Type | Air force |

| Garrison/HQ | Point Cook, Victoria |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | William Anderson |

Following the disbandment of the AFC, the AAC was a stop-gap measure intended to remain in place until the formation of a permanent and independent Australian air force. The corps' primary purpose was to maintain assets of the Central Flying School at Point Cook, Victoria, but several pioneering activities also took place under its auspices: AAC personnel set an Australian altitude record that stood for a decade, made the first non-stop flight between Sydney and Melbourne, and undertook the country's initial steps in the field of aviation medicine. The AAC operated fighters, bombers and training aircraft, including some of the first examples of Britain's Imperial Gift to arrive in Australia. As well as personnel, the RAAF inherited Point Cook and most of its initial equipment from the AAC.

Establishment and control

.jpeg)

In December 1919, the remnants of the wartime Australian Flying Corps (AFC) were disbanded, and replaced on 1 January 1920 by the Australian Air Corps (AAC), which was, like the AFC, part of the Australian Army. Australia's senior airman, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams, was overseas, and Major William Anderson was appointed commander of the AAC, a position that also put him in charge of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Point Cook, Victoria.[1][2] As Anderson was on sick leave at the time of the appointment, Major Rolf Brown temporarily assumed command; Anderson took over on 19 February.[3] CFS remained the AAC's sole unit, and Point Cook its only air base.[4]

The AAC was an interim organisation intended to exist until the establishment of a permanent Australian air service.[5] The decision to create such a service had been made in January 1919, amid competing proposals by the Army and the Royal Australian Navy for separate forces under their respective jurisdictions. Budgetary constraints and arguments over administration and control led to ongoing delays in the formation of an independent air force.[6]

By direction of the Chief of the General Staff, Major General Gordon Legge, in November 1919, the AAC's prime purpose was to ensure existing aviation assets were maintained; Legge later added that it should also perform suitable tasks such as surveying air routes.[5] The Chief of the Naval Staff, Rear Admiral Sir Percy Grant, objected to the AAC's being under Army control, and argued that an air board should be formed to oversee the AAC and the proposed Australian air force.[7] A temporary air board first met on 29 January 1920, the Army being represented by Williams and Brigadier General Thomas Blamey, and the Navy by Captain Wilfred Nunn and Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Goble, a former member of Britain's Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) then seconded to the Navy Office.[7][8] Williams was given responsibility for administering the AAC on behalf of the board.[7] A permanent Air Board overseen by an Air Council was formed on 9 November 1920; these bodies were made responsible for administering the AAC from 22 November.[9]

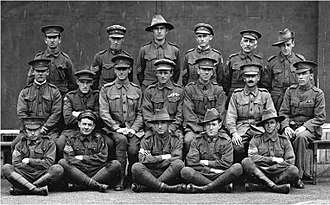

Personnel

Most members of the AAC were former AFC personnel.[10] In August 1919, several senior AFC pilots, including Lieutenant Colonel Oswald Watt, Major Anderson, and Captain Roy Phillipps, were appointed to serve on a committee examining applications for the AAC.[11] Some of the staffing decisions were controversial. At least three officers at the CFS, including the commanding officer, were not offered appointments in the new service.[12] Roy King, the AFC's second highest-scoring fighter ace after Harry Cobby, refused an appointment in the AAC because it had not yet offered a commission to Victoria Cross recipient Frank McNamara.[11][13] In a letter dated 30 January 1920, King wrote, "I feel I must forfeit my place in favor (sic) of this very good and gallant officer"; McNamara received a commission in the AAC that April.[11] Other former AFC members who took up appointments in the AAC included Captains Adrian Cole, Henry Wrigley, Frank Lukis, and Lawrence Wackett.[14] Captain Hippolyte "Kanga" De La Rue, an Australian who flew with the RNAS during the war, was granted a commission in the AAC because a specialist seaplane pilot was required for naval cooperation work.[11]

The corps' initial establishment was nine officers—commanding officer, adjutant, workshop commander, test pilot, four other pilots, and medical officer—and seventy other ranks.[15] In March 1920, to cope with the imminent arrival of new aircraft and other equipment, approval was given to increase this complement by a further seven officers and thirty-six other ranks. The following month the establishment was increased by fifty-four to make a total of 160 other ranks. An advertising campaign was employed to garner applicants.[16] According to The Age, applicants needed to be aged between eighteen and forty-five, and returned soldiers were preferred; all positions were "temporary" and salaries, including uniform allowance and rations, ranged from £194 to £450.[17] As the AAC was an interim formation, no unique uniform was designed for its members. Within three weeks of the AAC being raised, a directive came down from CFS that the organisation's former AFC staff should wear out their existing uniforms, and that any personnel requiring new uniforms should acquire "AIF pattern, as worn by the AFC".[16]

The AAC suffered two fatalities. On 23 September 1920, two Airco DH.9A bombers recently delivered from Britain undertook a search for the schooner Amelia J., which had disappeared on a voyage from Newcastle to Hobart. Anderson and Sergeant Herbert Chester flew one of the DH.9As, and Captain Billy Stutt and Sergeant Abner Dalzell the other. Anderson's aircraft landed near Hobart in the evening, having failed to locate the lost schooner, but Stutt and Dalzell were missing; their DH.9A was last sighted flying through cloud over Bass Strait. A court of inquiry determined the aircraft had crashed, and that the DH.9As may not have had adequate preparation time for their task, which it attributed to the low staffing levels at CFS. The court proposed compensation of £550 for Stutt's family and £248 for Dalzell's—the maximum amounts payable under government regulations—as the men had been on duty at the time of their deaths; Federal Cabinet increased these payments three-fold. Wreckage that may have belonged to the Amelia J. was found at Flinders Island the following year.[18]

Equipment

The AAC's initial complement of aircraft included twenty Avro 504K trainers and twelve Sopwith Pup fighters that had been delivered to CFS in 1919, as well as a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 and F.E.2, and a Bristol Scout. Seven of the 504Ks and one of the Pups were written off during the AAC's existence, leaving thirteen and eleven on strength, respectively.[19] The B.E.2 had been piloted by Wrigley and Arthur Murphy in 1919 on the first flight from Melbourne to Darwin, and was allotted to the Australian War Memorial in August 1920; the F.E.2 was sold in November 1920, while the Scout remained on strength and was still being flown by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in 1923.[20] In February 1920, the Vickers Vimy bomber recently piloted by Ross and Keith Smith on the first flight from England to Australia was flown to Point Cook, where it joined the strength of the AAC.[21]

In March 1920, Australia began receiving 128 aircraft with associated spares and other equipment as part of Britain's Imperial Gift to Dominions seeking to establish their own post-war air services.[10] The aircraft included Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5 fighters, Airco DH.9 and DH.9A bombers, and Avro 504s.[22] Most remained crated for eventual use by the yet-to-be formed RAAF, but several of each type were assembled and employed by the AAC.[10] One of the DH.9As was lost with the disappearance of Stutt and Dalzell in September 1920.[23]

Notable flights

On 17 June 1920, Cole, accompanied by De La Rue, flew a DH.9A to an altitude of 27,000 feet (8,200 m), setting an Australian record that stood for more than ten years. The effects of hypoxia exhibited by Cole and De La Rue intrigued the medical officer, Captain Arthur Lawrence, who subsequently made observations during his own high-altitude flight piloted by Anderson; this activity has been credited as marking the start of aviation medicine in Australia.[24][25] Later that month, flying an Avro 504L floatplane, De La Rue became the first person to land an aircraft on the Yarra River in Victoria.[26] On 22 July, Williams, accompanied by Warrant Officer Les Carter, used a DH.9A to make the first non-stop flight from Sydney to Melbourne.[24] A few days earlier, Williams and Wackett had flown two DH.9As to the Royal Military College, Duntroon, to investigate the possibility of taking some of the school's graduates into the air corps, a plan that came to fruition after the formation of the RAAF.[27][28]

.jpg)

Between July and November 1920, trials of the Avro 504L took place on the Navy's flagship, HMAS Australia, and later aboard the light cruiser HMAS Melbourne.[10][29] The trials on Melbourne, which operated in the waters off New Guinea and northern Australia, demonstrated that the Avro was not suited to tropical conditions as its engine lacked the necessary power and its skin deteriorated rapidly; Williams recommended that activity cease until Australia acquired a purpose-designed seaplane.[30]

The AAC performed several tasks in connection with the Prince of Wales' tour of Australia in 1920. In May, the AAC was required to escort the Prince's ship, HMS Renown, into Port Melbourne, and then to fly over the royal procession along St Kilda Road. The AAC had more aircraft than pilots available, so Williams gained permission from the Minister for Defence to augment AAC aircrew with former AFC pilots seeking to volunteer their services for the events. In August, the AAC was called upon at the last minute to fly the Prince's mail from Port Augusta, South Australia, to Sydney before he boarded Renown for the voyage back to Britain.[31]

During the Second Peace Loan, which commenced in August 1920, the AAC undertook a cross-country program of tours and exhibition flying to promote the sale of government bonds. Again Williams enlisted the services of former AFC personnel to make up for a shortfall in the number of AAC pilots and mechanics available to prepare and fly the nineteen aircraft allotted to the program. Activities included flyovers at sporting events, leaflet drops over Melbourne, and what may have been Australia's first aerial derby—at Serpentine, Victoria, on 27 August. Poor weather hindered some of the program, and four aircraft were lost in accidents, though no aircrew were killed. The Second Peace Loan gave AAC personnel experience in a variety of flying conditions, and the air service gained greater exposure to the Australian public.[32]

Disbandment and legacy

On 15 March 1921, the Brisbane Courier reported that the AAC would disband on 30 March, and be succeeded by a new air force.[33] The Australian Air Force was formed on 31 March, inheriting Point Cook and most of its initial personnel and equipment from the AAC. The "Royal" prefix was added to "Australian Air Force" that August.[34] Several officers associated with the AAC, including Williams, Anderson, Wrigley and McNamara, went on to achieve high rank in the Air Force. According to the RAAF's Pathfinder bulletin, the AAC "kept valuable aviation skills alive" until a permanent air force could be established. The corps was, further, "technically separate from the Army and Navy; its director answered to the Minister for Defence, through the Air Council. In effect, the AAC was Australia's first independent air force, albeit an interim one."[4]

Notes

- Sutherland, Command and Leadership, pp. 32–34

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 17–21

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 18, 20

- "The Australian Air Corps" (PDF). Pathfinder. No. 145. Air Power Development Centre. November 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 17–18

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 3–7

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 8–9

- Stephens, The Royal Australian Air Force, pp. 27–28

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 10–12

- "Australian Air Corps". The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 20

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 19

- Newton, Australian Air Aces, p. 43

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 20, 36, 191

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 18

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 22

- "Australian Air Corps". The Age. 22 March 1920. p. 6. Retrieved 18 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 25–26

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 4, 157–158, 162

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 157

- Campbell-Wright, An Interesting Point, pp. 66–71

- "Imperial Gift aircraft". The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 162

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 23

- Campbell-Wright, An Interesting Point, pp. 73–74

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 24

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 191–192

- "To lecture in Sydney". The Herald. Melbourne. 17 July 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 4 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 20, 215

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, p. 215

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 23–24

- Coulthard-Clark, The Third Brother, pp. 14, 24–25

- "Interstate". The Brisbane Courier. 15 March 1921. p. 6. Retrieved 4 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Royal Australian Air Force". The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. Oxford Reference. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

References

- Campbell-Wright, Steve (2014). An Interesting Point: A History of Military Aviation at Point Cook 1914–2014 (PDF). Canberra: Air Power Development Centre. ISBN 978-1-925-06200-7.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1991). The Third Brother: The Royal Australian Air Force 1921–39 (PDF). North Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-442307-2.

- Newton, Dennis (1996). Australian Air Aces: Australian Fighter Pilots in Combat. Fyshwick, Australian Capital Territory: Aerospace Publications. ISBN 978-1-875671-25-0.

- Stephens, Alan (2006) [2001]. The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-555541-7.

- Sutherland, Barry (ed.) (2000). Command and Leadership in War and Peace 1914–1975 (PDF). Canberra: Air Power Studies Centre. ISBN 978-0-642-26537-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)