Auchinleck manuscript

The Auchinleck Manuscript, NLS Adv. MS 19.2.1, currently forms part of the collection of the National Library of Scotland. It is an illuminated manuscript copied on parchment in the 14th century in London. The manuscript provides a glimpse of a time of political tension and social change in England. The English were continuing to reclaim their language and national identity, and to distance themselves from the Norman conquerors who had taken over the country after the Battle of Hastings 300 years before.

History of possession

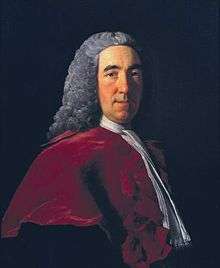

The manuscript is named after Alexander Boswell, Lord Auchinleck, who was a lawyer and supreme court judge in Edinburgh, Scotland. Lord Auchinleck lived from 1706 to 1782, and was the father of James Boswell who wrote The Life of Samuel Johnson. It is not known how Lord Auchinleck came to possess the manuscript, but it is believed he acquired it in 1740 and gave the book to the Advocates Library in Edinburgh in 1744.[1] It is a mystery who owned the book in the four hundred years from the time it was completed to when Lord Auchinleck first laid hands on it, but there are clues within. On some of the pages are names that have been added in, which are presumed to be previous owners and their family members. One of the quires of the manuscript is a list of Norman aristocracy, now assumed to be a version of the Battle Abbey Roll, and at the end of this list has been entered, in a different hand, the list of members from a family named Browne.[2] Also sprinkled throughout the text, others have entered their names individually for posterity, such as Christian Gunter[3] and John Harreis.[4] These names have never been researched against church or town records.[1]

Production

Auchinleck is believed to have been produced in London around 1340 by professional scribes who were laymen, not by monks, as was more usually the case with medieval manuscript texts. There is debate among scholars of Middle English, both as to how many scribes were involved in the production and writing-out of the text, and also as to whether they were merely copying the work from the original or exemplar, or were at the same time translating the works from French or Latin, rendering them incidentally into their own Middle English dialects.[5]

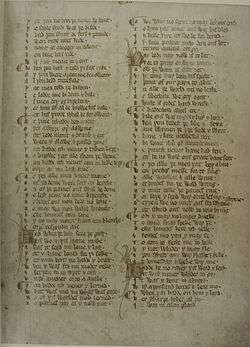

Through the use of palaeography (the study of ancient handwriting), it has been determined that there had to be at least four, perhaps five, different scribes. Some scholars have argued that there were six scribes, yet most agree that the majority of the manuscript is in the hand of one man, who it is believed translated most of the literature.[6] With this knowledge, when one looks at the photographs of the manuscript found on the website of the National Library of Scotland, it is easy to see the discrepancies in the actual handwriting of the scribes. Some is tight and regimented, attributed to Scribe 1, while some is more loosely written, as if the scribe did not make the correct adjustments for space and repeatedly ran out of room at the ends of the lines. While this has an entertaining visual effect when looking at the folios, or pages, its historical importance lies in the clues that it gives to the process of book production for private clients in a secular bookshop at an early period in the emergence of that industry.[7]

Language

The Auchinleck, in its present state, consists of forty-three pieces of literature. All of these works are in Middle English, but in various dialects such as were in use in different parts of England.[8] These dialects therefore suggest the diverse origins of the scribes, as for example from London as opposed to the south-west Midlands, because their written language probably reflected their manner of speech, and the variations in their spelling reflected what each had been taught: and these considerations again feed into the question of whether they were also translating.[9]

Since the language is consistent within each text, it is surmised that the scribes worked independently on each whole story. This contrasts with the method more usual in monasteries whereby the monks would copy directly from the exemplars one page at a time, with a catchword inscribed at the bottom corner for later collation. Although the Auchinleck manuscript includes catchwords, each scribe would have been responsible for all the pages of each of his assignments. From this mode of production, it is inferred that there was one production manager who, having contracted the work, oversaw the project and assigned separate stories to individual scribes, while acting as the person of contact with the patron or client if the book was indeed bespoke, or special order.[9]

Also of significance is that the Auchinleck manuscript is the first known anthology of English literature, particularly the largest collection of English romances up until that time. Previously the use of Latin or French had been almost exclusive in books, but English was beginning to be an acceptable language for pamphlets and literature.[10] It was during this time that the English were beginning to shift away from French and to form a separate identity, socially and politically, so it would follow that the use of "Inglisch", as it is referred to in the manuscript, in the written word would be a source of national unification.[11]

Illumination

The Auchinleck manuscript was illuminated, although not as ornately as the religious books of the era, such as Books of Hours. Unfortunately, many of the miniatures in the manuscript have been lost to thieves or people peddling the images for profit. The four remaining miniatures and the historiated letters suggest it was beautifully, yet modestly, decorated at one time. It has been determined through comparing artistic styles that the illustration was done by a handful of artists who illuminated other manuscripts commercially produced in the London area. This points to a group of illuminators, who it is believed collaborated on other works that have been preserved from the Middle Ages, who have been studied independently, and whose work is now being seen in a new light as a collective community.[12]

Assessment

The Auchinleck manuscript is not well known outside of scholarly circles, yet it is one of the most important English documents surviving from the Middle Ages. Within its folios, it tracks not only the literature of the period, reflecting the tastes of readers in Chaucer's time and how its subjects were increasingly diverging from religious topics, but also the development of a language as part of a national self-image.[13] It speaks to us of the independence of spirit with which the English people wanted to identify themselves as separate from their French cousins by claiming their own language in a fundamental expression, in their literature. As such, the manuscript is important in scholarship of the medieval romances, of London codicology (manuscript studies), of dialect and linguistic studies, and for the possibility (though unproven) that Chaucer himself may have had personal use of Auchinleck, based on claimed correspondences to his writings.

Contents

The Auchinleck manuscript is a codex of medieval narratives ranging from Saints' vitae to conversion tales. The order of the contents (and respective folio numbers) is as follows:

- The Legend of Pope Gregory (ff.1r-6v)

- f.6Ar / f.6Av (thin stub)

- The King of Tars (ff.7ra-13vb)

- The Life of Adam and Eve (E ff.1ra-2vb; ff.14ra-16rb)

- Seynt Mergrete (ff.16rb-21ra)

- Seynt Katerine (ff.21ra-24vb)

- St Patrick's Purgatory (ff.25ra-31vb)

- þe Desputisoun Bitven þe Bodi and þe Soule (ff.31vb-35ra stub)

- The Harrowing of Hell (ff.?35rb-?37rb or 37va stub)

- The Clerk who would see the Virgin (ff.?37rb or 37va stub-38vb)

- Speculum Gy de Warewyke (ff.39ra-?48rb stub)

- Amis and Amiloun (ff.?48rb stub-?61va stub)

- The Life of St Mary Magdalene (ff.?61Ava stub-65vb)

- The Nativity and Early Life of Mary (ff.65vb-69va)

- On the Seven Deadly Sins (ff.70ra-72ra)

- The Paternoster (ff.72ra-?72rb or ?72va stub)

- The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin (?72rb or ?72va stub-78ra)

- Sir Degaré (ff.78rb-?84rb stub)

- The Seven Sages of Rome (ff.?84rb stub-99vb)

- Gathering missing (c1400 lines of text)

- Floris and Blancheflour (ff.100ra-104vb)

- The Sayings of the Four Philosophers (ff.105ra-105rb)

- The Battle Abbey Roll (ff.105v-107r)

- f.107Ar / f.107Av (thin stub)

- Guy of Warwick (couplets) (ff.108ra-146vb)

- Guy of Warwick (stanzas) (ff.145vb-167rb)

- Reinbroun (ff.167rb-175vb)

- leaf missing.

- Sir Beues of Hamtoun (ff.176ra-201ra)

- Of Arthour & of Merlin (ff.201rb-256vb)

- þe Wenche þat Loved þe King (ff.256vb-256A thin stub)

- A Peniworþ of Witt (ff.256A stub-259rb)

- How Our Lady's Sauter was First Found (ff.259rb-260vb)

- Lay le Freine (ff.261ra-262A thin stub)

- Roland and Vernagu (ff.?262va stub-267vb)

- Otuel a Knight (ff.268ra-277vb)

- Many leaves lost, but some recovered as fragments.

- Kyng Alisaunder (L f.1ra-vb; S A.15 f.1ra-2vb; L f.2ra-vb; ff.278-9)

- The Thrush and the Nightingale (ff.279va-vb)

- The Sayings of St Bernard (f.280ra)

- Dauid þe King (ff.280rb-280vb)

- Sir Tristrem (ff.281ra-299A thin stub)

- Sir Orfeo (ff.299A stub-303ra)

- The Four Foes of Mankind (f.303rb-303vb)

- The Anonymous Short English Metrical Chronicle (ff.304ra-317rb)

- Horn Childe & Maiden Rimnild (ff.317va-323vb)

- leaf missing.

- Alphabetical Praise of Women (ff.324ra-325vb)

- King Richard (f.326; E f.3ra-vb; S R.4 f.1ra-2vb; E f.4ra-vb; f.327)

- Many leaves lost.

- þe Simonie (ff.328r-334v)

Notes

- Burnley & Wiggins 2003, "History and Owners".

- Burnley & Wiggins 2003, Auchinleck MS f. 107rd.

- Burnley & Wiggins 2003, Auchinleck MS f. 205ra.

- Burnley & Wiggins 2003, Auchinleck MS f. 247ra.

- Wiggins 2004, p. 11.

- Wiggins 2004, p. 10.

- Hanna 2005, p. 76.

- Sisam 1955, p. 265.

- Wiggins 2004, p. 12.

- Loomis 1962, p. 15.

- Calkin 2005, p. 8.

- Hanna 2005, p. 80.

- Sisam 1955, p. x.

References

- Burnley, David; Wiggins, Alison, eds. (June 2003). "The Auchinleck Manuscript". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 21 October 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calkin, Siobhain Bly (2005). Saracens and the Making of English Identity: The Auchinleck Manuscript. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415803090.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fein, Susanna, ed. (2016). The Auchinleck Manuscript: New Perspectives. Woodbridge: York Medieval Press/Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1903153659.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanna, Ralph (2005). London Literature, 1300–1380. Cambridge: Cambridge. ISBN 978-0521100175.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loomis, Laura Hibbard (1962). "The Auchinleck Manuscript and a Possible London Bookshop of 1330–1340". Adventures in the Middle Ages: A Memorial Collection of Essays and Studies. New York: Burt Franklin. pp. 156–57.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) First published in PMLA, 1942. 57 (3): 595–627. DOI 10.2307/458763.

- Sisam, Kenneth (1955). Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose. Oxford: Clarendon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiggins, Alison (2004). "Are Auchinleck Manuscript Scribes 1 and 6 the Same Scribe? The Advantages of Whole-Data Analysis and Electronic Texts". Medium Aevum. 73 (1): 10–26. doi:10.2307/43630696. ISSN 0025-8385. JSTOR 43630696.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)