Auchincruive Waggonway

The Auchincruive Waggonway or Whitletts Waggonway was a mineral railway or 'Bogey line' that transported mainly coal, eventually running from the north side of Ayr harbour at Newton to Blackhouse, Whitletts, Dalmilling, Gibbsyard, Auchincruive Holm, Annbank and Enterkine.[1] Apart from carrying coal to the harbour, lime kilns, quarries and a salt works were also served.[2]

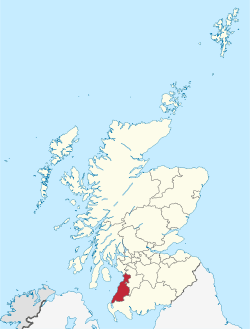

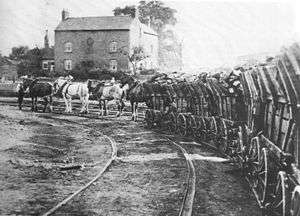

The Little Eaton Waggonway in 1908 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Ayr and Auchincruive, South Ayrshire |

| Dates of operation | 1784 circa–1872 circa |

| Successor | Abandoned |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | Unknown |

| Length | 10.5 miles (16.9 km) |

History

Writing in 1811 Aiton records that "Richard Oswald of Auchincruive, Esq; formed, some years ago, an iron rail-way, from his coal-works to near the town of Ayr, but could not obtain liberty to carry it through the Burgh-acres, to the harbour."[3] Aiton also notes that "Taylor Esq; has made a rail-way, of nearly the same length, from his coal-pits, in the lands of Newton, to the north harbour of Ayr."[4]

.jpg)

By 1792 the waggonway had reached Ayr harbour and a report of 1807 indicates that the old waggonway had been completely replaced.[5]

The waggonway was still in active use in 1838 when the Glasgow, Paisley, Kilmarnock and Ayr Railway was constructed with its terminus north of the river in Newton[6] and this necessitated the construction of a level manned crossing with gates.[7] The act authorising the construction of the line included an amendment that prevented the company from interfering with the waggonway's operation.[8] The GPK&AR's successor was the Glasgow & South Western Railway and they also were prevented from disrupting the smooth running of the waggonway when they extend their line south of the river.[9]

By 1837 the waggonway had been extended to Whitletts and by 1838 it had extended to Dalmilling,[10] reaching the Thorneyflat area after 1838 and the Auchincruive pits by 1846.[11] Annbank was in use by the 1860s and had closed by 1872.[12]

The pits

In the 1840s Messrs. George Taylor and Company owned pits near the Old Bridge; the Allison Pit near Russell Street; Newton Head Pit near Tam's Brig; as well as Saltfield and Green Pits near Newton Lodge.[13] Two pits that had closed by 1869 were Peelhill No. 1 just north of Oswald's Bridge and Peelhill No. 2 that lay between Mount Loudoun and Mount Stairs. The Holm Pit stood just downstream of Oswald's Bridge on the south side of the river and operated in the 1860s.[14] By 1839 nearly 70,000 tons of coal per year were being carried by the waggonway and exported by ship.[15] The Kerr Pit near Whitletts had closed by 1854,[16] Blackhouse Pit closed in 1863[17] and Auchincruive Pits by the late 1860s.[18]

Associated infrastructure

It is known that various sorts of sleepers were used, including stone blocks that were favoured on horse-worked lines, as they did not interfere with the centre of the track wooden sleepers do as they run right across the centre of the trackbed. 5 or 6 foot long wood sleepers made from beech with areas for the chairs have been found as have both wood pegs and wrought iron spikes.[19]

The waggonway gauge is not known, however from relics such as wooden railway sleepers estimates suggest 3 ft 6in, 4 ft 2in or 4 ft 8.5in.[20] It is possible that the gauge was changed at some point during its long history. Most of the route was single track with numerous passing loops.[21] No indication of formal signalling is recorded.

It is not clear what sort of rails were used in the early days as sand would have accumulated on 'L' shaped rails however waggons without a flange may have been used.[22] A wrought iron rail and a section of 'L' shaped cast iron rail have been recorded.[23]

Operation of the Waggonway

In keeping with other such waggonways the line was probably worked by a combination of gravity, manually, by horses and eventually steam locomotives. Most of the coal carried to the North Quay from the pits at Whitletts and Auchincruive was transported in trains of four, two or three ton waggons hauled by horses.[24] At the quay stood the wooden 'hurries' where the coal was tipped into the holds of the fleet of colliers[25] and most transported to Ireland. In 1857 four hurries are shown on the OS map with double tracks leading to each.[26]

A horse would usually haul between 5 and 7 coal waggons carrying 26 cwt each.[27] The use of steam locomotives is recorded and by 1860 they were used with the record of a death caused by an accident involving a locomotive returning from Annbank in 1865.[28]

The Oswald's Bridge to Annbank sections of the line involved substantial earthworks to create the cuttings and the embankments as well as the impressive Brockle Bridge that crossed the River Ayr below Tarholm, however it was only in use for around fifteen years from 1865 and was closed in the 1870s and lifted well before 1775.[29]

The waggons were tipped at the hurry on the harbour edge and one end opened allowing the coal to tumble into the hold of the collier in a process that took about a minute for each waggon.[30]

It is unclear how many steam locomotives were used however one is described as being about 25 horsepower, requiring no tender as the water tank was positioned above the boiler and the coal was stored on either side of the driver's cab.[31]

The routes

The waggonway had a complex history with possible changes of route and frequent abandonment of branches and sidings as many of the pits had relatively short working lives. The waggonway at its greatest extent had a 'main line' that ran from a complex of sidings running to the side of the quay at Newton on Ayr up through Wallacetown, onwards past Blackhouse, Whitletts and Dalmilling from whence it ran towards Thorneyflat with a branch to Gibbsyard, Stevenson and Wheatpark, whilst running onwards via New Barns to Holm where the terminus was for a number of years.[32][33] Crossing the River Ayr below Oswald's Bridge it continued sometime after 1865 towards Annbank via Brockle Quarry and Colvinston Farm to end near Enterkine No. 3 Pit,[34] at least five miles from Ayr.[35]

A number of other pits in the vicinity of the waggonway may also have been served by the waggonway although no hard evidence survives.

A large embankment ran across the Long Holm to the Holm Pit at Oswald's Bridge and this was removed the 1920s although it is till visible as a cropmark.[36]

The waggonway and pits today

Little or nothing survives at many of the various pits and associated spoil heaps, however sections of the track bed can be identified in such places as Cutting Wood[37] and Pheasant Nook near Auchincruive as well as the remains of waggonway bridges across the River Ayr at Brockle Quarry[38] and below Oswald's Bridge. Road overbridges survive intact at Oaklea Farm[39] and Colvinston Farm. Stone railway sleepers with the imprint of the chair base and two drilled holes survive as part of the Oaklea Bridge. Foundations of buildings and the abutment of the old bridge survive in the vicinity of the old Holm Pit.[40] A section of the old trackbed near the site of Annbaank House is used as a footpath and is known locally as the old line.[41]

Micro-history

Other contemporary waggonways existed on the Craigie[42] and on the Holmiston[43] estates with sections of trackbed traceable near the Holmiston lime kiln above Wallace's Heel Well. A very short waggonway appears to have existed at Wallacetown as far back as 1775.[44]

Robert Burns would have been familiar with the Auchincruive Waggonway however he never commented on them.[45]

See also

References

- Notes

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 120.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 109.

- Aiton, William (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 555.

- Aiton, William (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 556.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 105.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 27.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 112.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 27.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 29.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 111.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 117.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 127.

- Dunlop, Annie (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 203.

- Love, Dane (2010). The River Ayr Way. p. 29.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 113.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 117.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 123.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 127.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 128.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 132.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 108.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 106.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 128.

- Dunlop, Annie (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. p. 204.

- Dunlop, Annie (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. p. 204.

- "Ayr Sheet XXXIII.6, Newton Upon Ayr, Survey date: 1857 Publication date:1860". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 106.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 79.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 81.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 107.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 124.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 121.

- "Rail Map Online". Rail Map. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 120.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 29.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 130.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 79.

- "Ayrshire 033.04, Publication date: 1896, Revised: 1895". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 79.

- "Ayr Sheet XXXIII.4, Saint Quivox, Survey date:1857, Publication date:1860". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. p. 131.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 135.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 138.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. p. 133.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. p. 79.

- References

- Aiton, William (1811). General View of the Agriculture of the County of Ayr. Ayr : Wilson & Paul.

- Broad, Harry (1981). Rails to Ayr. 18th & 19th Century Coal Waggonways. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc.

- Dunlop, Annie (1953). The Royal Burgh of Ayr. Edinburgh : Oliver and Boyd.

- Love, Dane (2010). The River Ayr Way. Auchinleck : Carn Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9518128-8-4.

- Robertson, William (1905). Old Ayrshire Days. Ayr : Stephen & Pollock.

- Wham, Alasdair (2013). Ayrshire's Forgotten Railways. Usk : Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-729-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auchincruive Waggonway. |