Atmospheric ghost lights

Atmospheric ghost lights are lights (or fires) that appear in the atmosphere without an obvious cause. Examples include the onibi, hitodama and will-o'-wisp. They are often seen in humid climates.[1]

According to legend, some lights are wandering spirits of the dead, the work of devils (or yōkai), or the pranks of fairies. They are feared by some people as a portent of death. In other parts of the world, there are folk beliefs that supernatural fires appear where treasure is buried; these fires are said to be the spirits of the treasure or the spirits of humans buried with grave goods.[1] Atmospheric ghost lights are also sometimes thought to be related to UFOs.[2]

Some ghost lights such as St. Elmo's fire or the shiranui have been explained as optical phenomena of light emitted through electrical activity. Other types may be due to combustion of flammable gases, ball lightning, meteors, torches and other human-made fires, the misperception of human objects, and pranks.[2][3] Almost all such fires have received such naturalistic explanations.[2]

Examples from Australia

Min Min Light - a phenomenon believed to occur in outback Australia. The lights originate from before European colonization but have now become part of modern urban folklore.

Examples from Japan

In addition to the onibi and hitodama, there are other examples of atmospheric ghost lights in legend, such as the kitsunebi and the shiranui:

- Osabi (筬火, lit. "guide for yarn on loom fire")

- In the Nobeoka, Miyazaki Prefecture area, atmospheric ghost lights were described in first-hand accounts until the middle of the Meiji period. Two balls of fire would appear side by side on rainy nights at a pond known as the Misuma pond (Misumaike). It was said that a woman lent an osa (a guide for yarn on a loom) to another woman; when she returned to retrieve it, the two argued and fell into the pond. Their dispute became an atmospheric ghost fire, still said to be burning.[4] Legend has it that misfortune befalls anyone who sees the fire.[5]

- Obora

- Related in legends on Ōmi Island in Ehime Prefecture, it is said to be the spiritual fire of a deceased person.[6] In Miyakubo village, Ochi District in the same prefecture (now Imabari), they are known as oborabi. A legend exists of atmospheric ghost fires appearing above the sea or at graves;[7] these are sometimes the same kind of fire.[8]

- Kane no Kami no Hi (金の神の火, lit. "fire of the metal god")

- Related in legends on Nuwa Island, Ehime Prefecture and in the folklore publication Sōgō Nippon Minzoku Goi, this is a fire appearing at night on New Year's Eve behind the patron Shinto god's shrine on Nuwa Island. It is accompanied by sounds similar to human screaming, and is interpreted by local residents as a sign that the goddess of luck has appeared.[9]

- Kinka (金火, lit. "gold fire")

- This fire appeared in the fantasy collection, Sanshū Kidan. It is said to appear at Hachiman, Jōshikaidō and Komatsu as a fuse-like atmospheric ghost light.[10]

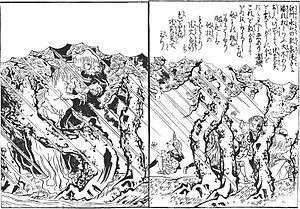

Sayō Shunsō Anzekyū Ika wo Mishi Mono from Nishihari Kaidan Jikki

Sayō Shunsō Anzekyū Ika wo Mishi Mono from Nishihari Kaidan Jikki

- Kumobi (蜘蛛火, lit. "spider fire")

- In a legend in Tenkō village, Shiki District, Nara Prefecture (now Sakurai), hundreds of spiders became a ball of fire in the air and one would die upon contact with it.[11] Similarly, in Tamashimayashima, Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture the Kumo no Hi is said to be the work of spiders. As a red ball of fire appears above the forest near the Inari shrine on the island, it is said to dance around above the mountains and forest and then disappear.[12] In Banshū (now Hyōgo Prefecture), according to Nishihari Kaidan Jikki (in the section "Sayō Shunsō Anzekyū Ika wo Mishi Mono") an atmospheric ghost light would appear in the village of Sayō, Sayō District, Banshū. Although "perhaps it is a spider fire", its details have not been made clear.[13]

- Gongorōbi (権五郎火, lit. "Gongorō fire")

- In legends from the area around Honjō-ji, Sanjō, Niigata Prefecture, Isono no Gongorō, after winning at gambling, was killed; his murder became an atmospheric ghost light. At a nearby family farm Gongorōbi is a sign of impending rain, and peasants who see it hurry to retrieve their rice-drying racks.[14]

- Jōsenbi (地黄煎火, lit. "Jōsen fire")

- In a Yomihon (Ehon Sayo Shigure) from the Edo period, at Minakuchi, Ōmi (now Kōka, Shiga Prefecture) there was a person who made a livelihood out of selling jōsen (candy made from the sap of Rehmannia glutinosa, boiled into a paste) who was killed by a robber. It is said that the vendor became an atmospheric ghost fire, floating on rainy nights.[15]

- Sōrikanko

- Told in legends of Shioire, Oodachi, Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture, its name means "the Kanko of Shioiri village".[16] A beautiful girl named Kanko received many marriage proposals, but refused them all since she loved someone else. One of her suitors buried her alive in the Niida River, and her atmospheric ghost light became able to fly. When a cement factory was later built there, a small shrine to Kanko was included.[17]

- Susuke Chōchin (煤け提灯, lit. "stained paper lantern")

- Told in the legends of Niigata Prefecture, on rainy nights it would fly airily around a place where bodies are washed for burial.[18]

- Nobi (野火, lit. "field fire")

- A legend from Nagaoka District, Tosa Province (now Kōchi Prefecture), nobi appears in a variety of locations. An umbrella-sized fire would float, bursting apart into star-like lights that would spread from four or five shaku to several hundreds of meters apart. It is said that by putting saliva on a zōri and calling it, it would dance brilliantly in the sky above one's head.[19]

Cultural references

English Musician, Benson Taylor performs under the name Atmospheric Ghost Lights.

Notes

- Tsunoda 1979, pages 11-53

- Kanda 1992, pages 275-278.

- Miyata Noboru (2002). 妖怪の民俗学・日本の見えない空間. ちくま学芸文庫. Chikuma Shobo. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-4-480-08699-0.

- 柳田國男 (1977). 妖怪談義. Kodansha academic library. ja:講談社. p. 214. ISBN 978-4-06-158135-7.

- 加藤恵 (December 1989). "県別日本妖怪事典". 歴史読本. 34 (24(通巻515号)): 332. 雑誌 09618-12.

- 日野巌・日野綏彦 (2006). "日本妖怪変化語彙". In Kenji Murakami (ed.). 動物妖怪譚. 中公文庫. 下. 中央公論新社. p. 243. ISBN 978-4-12-204792-1.

- Folklore Institute 1955, p.287

- 村上健司編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. p. 88. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- Folklore Institute 1955, p. 385.

- 堀麦水 (2003). "三州奇談". 江戸怪異綺想文芸大系. 5. 高田衛監修. 国書刊行会. p. 164. ISBN 978-4-336-04275-0.

- Inoue Enryō (1983). おばけの正体 [Identity of the ghost]. 新編妖怪叢書. 6. 国書刊行会. p. 23. BN01566352.

- 佐藤米司編 (1979). 岡山の怪談. 岡山文庫. Japan Educational Publishing. p. 40. BA7625303X.

- 小栗栖健治・埴岡真弓編著 (2001). 播磨の妖怪たち 「西播怪談実記」の世界. 神戸新聞綜合出版センター. pp. 161–164. ISBN 978-4-343-00114-6.

- 外山暦郎 (1974). "越後三条南郷談". In 池田彌三郎他編 (ed.). 日本民俗誌大系. 7. 角川書店. p. 203. ISBN 978-4-04-530307-4.

- 速水春暁斎 (2002). "絵本小夜時雨". In 近藤瑞木編 (ed.). 百鬼繚乱 江戸怪談・妖怪絵本集成. 国書刊行会. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-4-336-04447-1.

- 佐藤清明 (1935). 現行全國妖怪辞典. 方言叢書. 中國民俗學會. p. 28. BA34159738.

- 森山泰太郎・北彰介 (1977). 青森の伝説. 日本の伝説. 角川書店. pp. 27–28. BN03653753.

- 民俗学研究所編著 (1955). 綜合日本民俗語彙. 2. 柳田國男監修. 平凡社. p. 775. BN05729787.

- 高村日羊 (August 1936). "妖怪". 民間伝承 (12): 7–8.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Will-o'-the-wisps. |