Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (/ˌæθəˈniːəs/; Ancient Greek: Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, Athēnaios Naukratitēs or Naukratios; Latin: Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd century AD. The Suda says only that he lived in the times of Marcus Aurelius, but the contempt with which he speaks of Commodus, who died in 192, shows that he survived that emperor. He was a contemporary of Adrantus.[1]

Athenaeus of Naucratis | |

|---|---|

| Born | Late second century AD Naucratis, Roman Empire (modern-day Egypt) |

| Died | Early third century AD Unknown |

| Occupation | Writer, grammarian, and rhetorician |

| Notable works | Deipnosophistae |

Several of his publications are lost, but the fifteen-volume Deipnosophistae mostly survives.

Publications

Athenaeus himself states that he was the author of a treatise on the thratta, a kind of fish mentioned by Archippus and other comic poets, and of a history of the Syrian kings. Both works are lost.

The Deipnosophistae

The Deipnosophistae, which means "dinner-table philosophers," survives in fifteen books. The first two books, and parts of the third, eleventh and fifteenth, are extant only in epitome, but otherwise the work seems to be entire. It is an immense store-house of information, chiefly on matters connected with dining, but also containing remarks on music, songs, dances, games, courtesans, and luxury. Nearly 800 writers and 2500 separate works are referred to by Athenaeus; one of his characters (not necessarily to be identified with the historical author himself) boasts of having read 800 plays of Athenian Middle Comedy alone. Were it not for Athenaeus, much valuable information about the ancient world would be missing, and many ancient Greek authors such as Archestratus would be almost entirely unknown. Book XIII, for example, is an important source for the study of sexuality in classical and Hellenistic Greece, and a rare fragment of Theognetus' work survives in 3.63.

The Deipnosophistae professes to be an account given by an individual named Athenaeus to his friend Timocrates of a banquet held at the house of Larensius (Λαρήνσιος; in Latin: Larensis), a wealthy book-collector and patron of the arts. It is thus a dialogue within a dialogue, after the manner of Plato, but the conversation extends to enormous length. The topics for discussion generally arise from the course of the dinner itself, but extend to literary and historical matters of every description, including abstruse points of grammar. The guests supposedly quote from memory. The actual sources of the material preserved in the Deipnosophistae remain obscure, but much of it probably comes at second-hand from early scholars.

The twenty-four named guests[2] include individuals called Galen and Ulpian, but they are all probably fictitious personages, and the majority take no part in the conversation. If the character Ulpian is identical with the famous jurist, the Deipnosophistae may have been written after his death in 223; but the jurist was murdered by the Praetorian Guard, whereas Ulpian in Athenaeus dies a natural death.

The complete version of the text, with the gaps noted above, is preserved in only one manuscript, conventionally referred to as A. The epitomized version of the text is preserved in two manuscripts, conventionally known as C and E. The standard edition of the text is Kaibel's Teubner. The standard numbering is drawn largely from Casaubon.

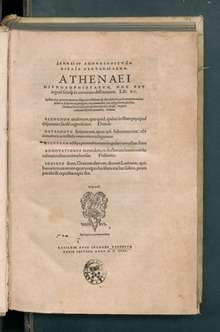

The encyclopaedist and author Sir Thomas Browne wrote a short essay upon Athenaeus[3] which reflects a revived interest in the Banquet of the Learned amongst scholars during the 17th century following its publication in 1612 by the Classical scholar Isaac Casaubon.

Death

One of Athenaeus' friends, Timocrates, wrote about the untimely death of Athenaeus in the Athenaeum. It describes the tale of angry peasants who believed that Athenaeus' writings directly contradicted their personal beliefs of the Mithras cult. One night in 191 A.D., they kidnapped him and threatened to kill him if he did not stop writing. When they discovered that he continued writing the Deipnosophistae, twenty-three men stormed into his home and strangled him to death. It is unclear whether Athenaeus finished his work on his own or Timocrates finished it for him, as most of the Athenaeum is lost.[4]

First patents

Athenaeus described what may be considered the first patents (i.e. exclusive right granted by a government to an inventor to practice his/her invention in exchange for disclosure of the invention). He mentions that in 500 BC, in the Greek city of Sybaris (located in what is now southern Italy), there were annual culinary competitions. The victor was given the exclusive right to prepare his dish for one year.[5]

See also

References

- Smith, William (1867), "Adrantus", in Smith, William (ed.), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1, Boston, p. 20

- Kaibel, Georg (1890). Athenaei Naucratitae Dipnosophistarum Libri XV, Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner. pp. 561–564.

- Sir Thomas Browne, From a Reading of Athenaeus

- "Athenaeus." LacusCurtius •. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

- M. Frumkin, "The Origin of Patents", Journal of the Patent Office Society, March 1945, Vol. XXVII, No. 3, pp 143 et Seq.

Further reading

- David Braund and John Wilkins (eds.), Athenaeus and his world: reading Greek culture in the Roman Empire, Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2000. ISBN 0-85989-661-7.

- Christian Jacob, The Web of Athenaeus, (Hellenic studies, 61), Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies at Harvard University, 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Athenaeus |

- Digital Athenaeus Project - University of Leipzig

- Digital Athenaeus - Casaubon-Kaibel reference converter

- Works by Athenæus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Athenaeus at Internet Archive

- Works by Athenaeus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Deipnosophists, translated by C. D. Yonge, at The Literature Collection

- The Deipnosophists, long excerpts in searchable HTML format, at attalus.org

- The Deipnosophists, translated up to Book 9 with links to complete Greek original, at LacusCurtius

- The Deipnosophists, open source XML version by the University of Leipzig, at Open Greek & Latin Project