Astraspida

Astraspida, or astraspids, are a small group of extinct armored jawless vertebrates, which lived in the Middle Ordovician (about 450 million years ago) in North America.[1] They are placed among the Pteraspidomorphi because of the large dorsal and ventral shield of their head armor. They are represented by a single genus, Astraspis, including possibly two species, A. desiderata and A. splendens[2] but their remains are fairly abundant in Ordovician sandstones of the USA (Colorado, Arizona, Oklahoma, Wyoming) and Canada (Quebec). The head armor of Astraspis is rather massive, with a series of ten gill openings lining the margin of the dorsal shield, and laterally placed eyes. The dorsal shield is ribbed by strong longitudinal crests, and the tail is covered with large, diamond-shaped scales. They are often grouped together with the Arandaspidida.[3]

| Astraspida Temporal range: Middle Ordovician | |

|---|---|

| |

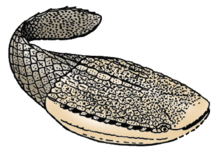

| An Astraspis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | †Heterostracomorphi |

| Infraclass: | Astraspida Berg 1940 |

| Orders | |

| |

Characteristics

Astraspids are characterized by a dermal ornamentation of large, mushroom shaped tubercles of fine-tubuled dentine ("astraspidine"), covered with a thick, glassy cap of enameloid.[4]

Astraspids and eriptychiids were the first Ordovician vertebrates ever discovered in the 19th century, and they have long been the only known Ordovician vertebrates, until the discovery of the arandaspids, in the 1970s. Therefore, their structure, though poorly known, has often been used in evolutionary scenarios to illustrate the primitive condition of the vertebrate dermal skeleton.[5] Because of the acellular structure of their dermal skeleton, they were first regarded as heterostracans. Now, we know that they are widely different from heterostracans, in particular in retaining about ten separate external gill openings. However, they share with heterostracans the relatively dorsal position of these openings. Their dorsal and ventral shield is made up by numerous polygonal platelets of aspidine, ornamented with large dentine tubercles capped with a thick enameloid layer. Nothing is known of their internal anatomy, but they possessed a sensory-line system housed in grooves of the dermal plates.

Taxonomy

Taxonomy based on the work of Mikko's Phylogeny Archive[6], Nelson, Grande and Wilson 2016[7] and van der Laan 2018.[8]

- Order †Astraspidiformes Berg 1940

- Family †Astraspididae Eastman 1917

- Genus †Astraspis Walcott 1892

- Genus †Pycnaspis Ørvig 1958

- Family †Astraspididae Eastman 1917

- Order †Tesakoviaspidida Karatajūtė-Talimaa & Moya 2004 [Tesakoviaspidiformes Arratia, Wilson & Cloutier 2004]

- Family Tesakoviaspididae Karatajūtė-Talimaa & Moya 2004

- Genus †Kodinskaspis Dzik & Moskalenko 2016

- Genus †Tesakoviaspis Karatajūtė-Talimaa 1978 ex Karatajūtė-Talimaa & Meredith-Smith 2004

- Family Tesakoviaspididae Karatajūtė-Talimaa & Moya 2004

References

- Denison, R. H. (1967). Ordovician vertebrates from Western United States. Fieldiana: Geology, 16, 269-288.

- Ørvig, T. (1958). Pycnaspis splendens new genus, new species, a new ostracoderm from the Upper Ordovician of North America. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 108, 1-23.,

- Philippe Janvier (1997). "Astraspida". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- Sansom, I. J. and Smith, P. (in press). Astraspis - The anatomy and histology of an Ordovician fish. Palaeontology.

- Smith, M. M. (1991). Putative skeletal neural crest cells in Early Late Ordovician vertebrates from Colorado. Science, 251, 301-303.

- Haaramo, Mikko (2003). "Pteraspidomorphi". in Mikko's Phylogeny Archive. After Carroll, 1988, and Janvier, 1997. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Nelson, Joseph S.; Grande, Terry C.; Wilson, Mark V. H. (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118342336.

- van der Laan, Richard (2017). "Family-group names of fossil fishes". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)