Astrarium of Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio

The Astrarium of Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio was a complex astronomical clock built between 1348 and 1364 in Padova, Italy, by the doctor and clock-maker Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio. The Astrarium had seven faces and 107 moving parts; it showed the positions of the sun, the moon and the five planets then known, as well as religious feast days. It was one of the first mechanical clocks to be built in Europe.

The Tractatus astrarii

Dondi documented the Astrarium in detail in the Tractatus astrarii, which is the earliest complete surviving description of its kind; the St Albans abbey clock designed by Richard of Wallingford predates it, but survives only as fragments (reconstructed by John North).[1]:8[2]:2:364–5 In the introduction, Dondi writes that his machine was built in accordance with the 13th-century Theorica planetarum of Campano di Novara, and to demonstrate the validity of the descriptions of the motion of heavenly bodies of Aristotle and Avicenna. The Tractatus survives in twelve manuscript sources. The autograph in the Biblioteca Capitolare of Padova (MS. D39) and a copy of it, also in Padova, are certainly the work of Dondi. The other sources are rewritten versions of the autograph, to which Dondi's contribution is as yet unclear.[3] The autograph manuscript was published in 1987 in a critical edition with colour facsimile and French translation by Poulle as the first volume of the Opera omnia of Jacopo and Giovanni Dondi.[4]

Description

The astrarium was considered to be a marvel of its day. Giovanni Manzini of Pavia writes (in 1388) that it is a work "full of artifice, worked on and perfected by your hands and carved with a skill never attained by the expert hand of any craftsman. I conclude that there was never invented an artifice so excellent and marvelous and of such genius".

Dondi writes that he obtained the idea of an astrarium from the Theorica Planetarum of Giovanni Campano da Novara, who describes the construction of the equatorium.

The astrarium was primarily a clockwork equatorium with astrolabe and calendar dials, and indicators for the sun, moon, and planets. It provided a continuous display of the major elements of the solar system and of the legal, religious, and civil calendars of the day. Dondi's intention was that it would help people's understanding of astronomical and astrological concepts. (Astrology was then considered a subject worthy of study by the intellectual elite and was taken reasonably seriously.)

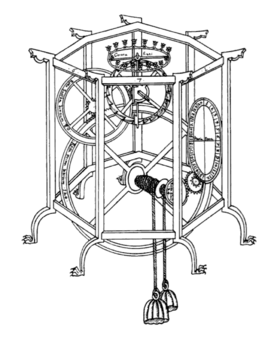

The astrarium stood about 1 metre high, and consisted of a seven-sided brass or iron framework resting on 7 decorative paw-shaped feet. The lower section provided a 24-hour dial and a large calendar drum, showing the fixed feasts of the church, the movable feasts, and the position in the zodiac of the moon's ascending node. The upper section contained 7 dials, each about 30 cm in diameter, showing the positional data for the Primum Mobile, Venus, Mercury, the moon, Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars.

Dondi constructed the clock, with its 107 gear wheels and pinions, entirely by hand. No screws were used, and every part was held together by over 300 tapering pins and wedges, with some parts being soldered. Most of the wheels have triangular shaped teeth, although some are blunt-nosed. In some cases, Dondi used near-elliptical wheels, in order to more accurately model the irregular motions of the planets (using the Ptolemaic epicycles rather than the ellipses as later worked out by Johannes Kepler). On some of these wheels, the teeth varied in size and spacing along the wheel's periphery. To indicate dimensions in his descriptions, Dondi used units such as the width of a goose quill, the thickness of a blade of a knife, or the breadth of a man's thumb.

For data on the motion of the planets, he consulted the Alfonsine tables, compiled in about 1272.

The clock movement

The clock movement had a balance wheel regulated to beat at the rate of 2 seconds. Its simple wheel train turned a dial marked on the margin with a scale of 24 equal hours and 10-minute intervals. The dial rotated anticlockwise against a fixed pointer, showing mean time, and could be adjusted if necessary by intervals of 10 minutes of time by sliding out a pinion of 12 teeth that meshed with the 144 teeth of the main dial. On each side of the clock dial was a fixed plate or 'tabula orientii', graduated with months and days of the Julian calendar for the purpose of determining the times of the rising and setting of the mean sun for the latitude of Padova (about 45°deg N). At the time the clock was made, the dates of the solstices were 13 June and 13 December (Old style or Julian Calendar).

The calendar wheel

The annual calendar wheel or drum in the lower section was about 40 cm across. This drove the calendar of movable feasts, and the dials above. Around the outside of the wheel was a broad band divided into 365 strips, each containing numbers that indicated the length of daylight, the dominical letter, the name of the saint for that day, and the day of the month. Alternate months were gilded and silvered, and the engraved letters filled alternately with red and blue enamel. Dondi didn't introduce any indications or allowances for leap year - he recommended stopping the clock for the entire day.

The Primum Mobile dial

Directly above the 24-hour dial is the dial of the Primum Mobile, so called because it reproduces the diurnal motion of the stars and the annual motion of the sun against the background of stars. It is basically an astrolabe drawn using a south polar projection, with a fixed tablet and a rete of special design that rotated once in a sidereal day. The rete was provided with 365 teeth, but was driven by a wheel with 61 teeth which made 6 turns in 24 hours. Thus the rete rotated once in 365/366 of a mean solar day, which equated 366 successive meridian transits of the vernal equinox with 365 similar transits of the sun. Dondi realised that his approximations didn't correspond with the exact length of the solar year, and recommended stopping the clock occasionally so that it could be adjusted.

Planetary dials

Each of the 'planetary' dials used complex clockwork to produce reasonably accurate models of the planets' motion. These agreed reasonably well both with Ptolemaic theory and with observations. For example, Dondi's dial for Mercury uses a number of intermediate wheels, including: a wheel with 146 teeth, two oval wheels with 24 irregularly shaped teeth that meshed together, a wheel with 63 internal (facing inwards) teeth that meshed with a 20 tooth pinion. The 63-tooth wheel made one rotation a year, non-uniformly because of the oval driving wheels, and made the main indicator wheel rotate through 63/20 × 12 signs of the zodiac each year. This is equivalent to 37 signs and 24°, a good approximation to the value of 37 signs and 24° 43' 23" required by theory.

Later history

In 1381 Dondi presented his clock to Gian Galeazzo Visconti, duke of Milan, who installed it in the library of his castle in Pavia. It remained there until at least 1485. It may have been seen and drawn by Leonardo da Vinci.[1] The fate of the clock is unknown.

Because Dondi described most of the more complex components of his clock in his manuscripts in considerable detail, it has been possible for modern clockmakers to build convincing - if sometimes speculative - reconstructions. Seven such reconstructions were built by Peter Haward of Thwaites and Reed, London; examples of these can be found in the Smithsonian Institution and The Time Museum Illinois. There is also a reconstruction in the Musée international d'horologerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, with the signature of Luigi Pippa.

References

- Silvio A. Bedini, Francis R. Maddison (1966). Mechanical Universe: The Astrarium of Giovanni de' Dondi. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series 56 (5): 1–69. (subscription required)

- J. D. North (1976). Richard of Wallingford: an Edition of his Writings. 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tiziana Pesenti (1992) "Dondi dall'Orologio, Giovanni" (in Italian). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 41. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Accessed August 2013.

- Giovanni Dondi dall' Orologio, Emmanuel Poulle (ed., trans.) (1987–1988) Johannis de Dondis Padovani Civis Astrarium. 2 vols. Opera omnia Jacobi et Johannis de Dondis. [Padova]: Ed. 1+1; Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Further reading

- Henry C. King, John R. Millburn (1978). Geared to the Stars: the evolution of planetariums, orreries, and astronomical clocks. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Granville Hugh Baillie, Herbert Alan Lloyd, Francis Allan Burnett Ward (ed.) (1974). The planetarium of Giovanni de Dondi, citizen of Padua: A manuscript of 1397, translated by G. H. Baillie, with additional material from another Dondi manuscript translated by H. Alan LLoyd. London: The Antiquarian Horological Society.

- Catherine Cardinal, Jean-Michel Piguet (1999). Catalogue d'oeuvres choisies. La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland: Institut l'homme et le temps. Translated as:

- ——— , Patrick and Carol Collins (trans.) (2002). Catalogue of selected pieces. La Chaux-de-Fonds: Institut l'homme et le temps.