Asiodiplatys

Asiodiplatys is a monotypic genus containing the single species Asiodiplatys speciousus, an extinct species of earwig in the family Protodiplatyidae.[1][2] It had long and thin cerci that were very different from modern species of Dermaptera, but tegmina and hind wings that folded up into a "wing package" that are like modern earwigs.[3] Like Archidermapteron martynovi, the only clear fossil of the species was found in Russia.[4]

| Asiodiplatys | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Dermaptera |

| Family: | †Protodiplatyidae |

| Genus: | †Asiodiplatys Vishnyakova, 1980 |

| Species: | †A. speciousus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Asiodiplatys speciousus Vishnyakova, 1980 | |

Discovery

Like other extinct species of earwig, little is known about how Asiodiplatys speciousus was discovered due to the ambiguity of the reports about it, and the fact that only one fossil of it was ever found.[3] The reason for this is that the environment that most earwigs live in often prevents preservation, because dead organisms in soil and other crevices quickly rot and dissolve away.[3] It is known, however, that the sole fossil of it was found some time in the early 1900s by a team of Russian entomologists.[3]

Characteristics

Unlike its relative, Archidermapteron martynovi, Asiodiplatys speciousus had cerci, or rear appendages similar to antennae, that were less than the length of their abdomen.[4] By contrast, Archidermapteron martynovi had cerci that were not only longer than their abdomen, but longer than their abdomen and thorax combined.[5] The size of Asiodiplatys speciousus's cerci is much more similar to the cerci of modern-day earwigs, such as most male Common earwigs, or Forficula auricularia.[6]

However, the cerci of Asiodiplatys speciousus and Forficula auricularia differ greatly on one major front. Asiodiplatys speciousus had cerci that were more bead-like, or filiform, than the thicker cerci, specifically known as forceps, of most other earwigs.[4] From the fossil, it can be noted that Asiodiplatys speciousus's cerci were thin, almost identical to their antennae,[4] while Forficula auricularia's cerci are the opposite.[6] One of the key characteristics of the Forficulina suborder is the existence of large, thick, basally broadened and crenulate-toothed forceps, which is notably absent on Asiodiplatys speciousus. The only species of earwigs with these uncharacteristically-thinner cerci are earwigs in the suborders Arixeniina and Hemimerina, which are rare and contain few individuals.[7]

In order to open their wings, extant species of Forficulina use their cerci because their wings fold into a "package" due to internal elasticity.[8] While Asiodiplatys speciousus had such a wing package, like other earwigs in the Archidermaptera suborder,[4] they also had long segmented cerci, as mentioned above. This means that the unsegmented cerci of extant species of Forficulina is probably not an adaptation for wing folding. Instead, it is likely that the cerci of Asiodiplatys speciousus served a function similar to that of an insect's antennae: a sense of touch.[3]

Phylogenesis

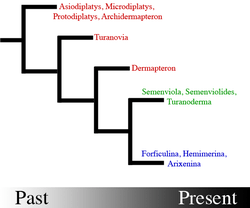

According to the research of Dr. Fabian Hass, an entomologist who specializes in earwig biology,[9][10] the relative age of this species compared to other genera in the suborder Archidermaptera can be approximated based upon the research of Dr. R. Willmann.[3] According to Willmann, the genus Asiodiplatys, and therefore also the species Asiodiplatys speciousus, existed longer ago than the genera Dermapteron and Turanovia, but around the same time period as Archidermapteron, Microdiplatys, and Protodiplatys.[11] He bases this assumption on the shape of the fossils' cerci: Archidermateron, Asiodiplatys, Microdiplatys, and Protodiplatys all had cerci that were long and filiform, while Dermapteron had cerci that were short and more forcep-like.[12] Therefore, Turanovia would have been in between both groups.

However, this does not necessarily mean that Willmann's hypothesis is correct.[3] According to Dr. V. N. Vishnyakova, in an article written by her in the Paleontological Journal, Willmann could be correct on some fronts, but wrong on others.[13] Although Vishnyakova did not address Willmann specifically (she wrote about it ten years earlier), her paper disagrees with Willmann's on the basis of the ordering of Semenviola, Semenoviolides, and Turanoderma, which are extinct genera in Forficulina. Mainstream science is still unsure of whose chart is more accurate: it all depends on the definitions of certain taxon, which can change from person to person.[3]

References

- "Taxa display – Asiodiplatys speciousus". Dermaptera Species File. speciesfile.org. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- "Taxa display – Asiodiplatys". Dermaptera Species File. speciesfile.org. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Hass, Fabian (January 1996). "Archidermaptera". Tree of Life. The University of Arizona College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and The University of Arizona Library. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Dr. A.P. Rasnitsyn and Dr. R.L. Kaesler (1992). "Tree of Life Web Project – Details for Media ID# 4938". Tree of Life. Russian Academy of Science. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Dr. A.P. Rasnitsyn and Dr. R.L. Kaesler (1992). "Tree of Life Web Project – Details for Media ID# 852". Tree of Life. Russian Academy of Science. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- H.V. Weems Jr, Paul E. Skelley (July 1998). "European earwig – Forficula auricularia Linnaeus". Featured Creatures. Florida: Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Hass, Fabian (July 1996). "Dermaptera". Tree of Life. The University of Arizona College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and The University of Arizona Library. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Kleinow, W. (1966) Untersuchungen zum Flügelmechanismus der Dermapteren. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Ökologie der Tiere, 56, 363-416.

- Hass, Fabian (2007). "Welcome to the Earwig Research Centre". Earwig Research Centre. Heilbronn. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Hass, Fabian (2007). "Earwig Research Centre :: People". Earwig Research Centre. Heilbronn. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-12.

- Willmann, R. (1990) Die Bedeutung paläontologischer Daten für die zoologische Systematik. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Zoologischen Gesellschaft, 83, 277-289.

- Dr. A.P. Rasnitsyn and Dr. R.L. Kaesler (1992). "Tree of Life Web Project – Details for Media ID# 3084". Tree of Life. Russian Academy of Science. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Vishnyakova, V.N. (1980) Earwigs from the Upper Jurassic of the Karatau range. Paleontological Journal, 1, 78-95.