Asaf-ud-Daula

Asaf-ud-Daula (Hindi: आसफ़ उद दौला, Urdu: آصف الدولہ) (b. 23 September 1748 – d. 21 September 1797) was the Nawab wazir of Oudh (a vassal of the British) ratified by Shah Alam II, from 26 January 1775 to 21 September 1797,[1] and the son of Shuja-ud-Dowlah. His mother and grandmother were the Begums of Oudh.

Asaf-ud-Daula | |

|---|---|

| Mirza (Royal title) Nawab Wazir of Awadh Khan Bahadur Adan Muqaam[nt 1] | |

Water colour in style of Zoffany | |

| Reign | 1775–1797 |

| Predecessor | Shuja-ud-Daula |

| Successor | Wazir Ali Khan |

| Full name

Muhammad Yahiya Meerza Amani Asaf-ud-Daula | |

| Born | 23 September 1748 Faizabad, Kingdom of Oudh |

| Died | 21 September 1797 (aged 48) Lucknow, Kingdom of Oudh |

| Buried | Bara Imambara, Lucknow |

| Issue

adopted son Wazir Ali Khan | |

| Father | Shuja-ud-Daula |

| Mother | Umat uz-Zohra Begum Sahiba |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Mughal Empire |

| Service/ | Nawab of Oudh |

| Rank | Subadar, Grand Vizier, Nawab |

Reign

Asaf-ud-Daula became nawab at the age of 26, on the death of his father, Shuja-ud-daula, on 28 January 1775.[2] He assumed the throne with the aid of the British East India Company, outmanoeuvring his younger brother Saadat Ali who led a failed mutiny in the army. British Colonel John Parker defeated the mutineers decisively, securing Asaf-ud-Daula's succession. His first chief minister was Mukhtar-ud-Daula who was assassinated in the revolt.[3]

The other challenge to Asaf's rule was his mother Umat-ul-Zohra (better known as Bahu Begum), who had amassed considerable control over the treasury and her own jagirs and private armed forces. She at one pointed invited the Company to intervene in her favour in the appointment of ministers against Asaf. When Shuja-ud-Daula died he left two million pounds sterling buried in the vaults of the zenana. The widow and mother of the deceased prince claimed the whole of this treasure under the terms of a will which was never produced. When Warren Hastings pressed the nawab for the payment of debt due to the Company, he obtained from his mother a loan of 26 lakh (2.6 million) rupees, for which he gave her a jagir (land) of four times the value; of subsequently obtained 30 lakh (3 million) more in return for a full acquittal, and the recognition of her jagirs without interference for life by the Company. These jagirs were afterwards confiscated on the ground of the begum's complicity in the rising of Chait Singh, which was attested by documentary evidence.[4] Ultimately this removed Umat-ul-Zohra as an obstacle to Asaf's reign.

In the aftermath of Saadat's revolt, Asaf sought to restructure the government particularly by appointing nobles favourable to his cause and British officers to his miliary. Asaf appointed Hasan Riza Khan as his chief minister. Although he had little experience in administration, his assistant Haydar Beg Khan turned out to be a valuable support. Tikayt Ray was appointed finance minister.[3]

He was known for his generosity, particularly the offering of food and public employment in times of famine. Notably, the Bara Imambara, a mosque in Lucknow, was constructed during his reign by destitute workers seeking employment. A popular saying of the time of his benevolence: jisko na de maulā, usko de Asaf-ud-daulā "to whom even God does not give, Asaf-ud-Daula gives."[5]

He was painted several times by Johann Zoffany.[6]

Shifting the capital

In 1775 he moved the capital of Awadh from Faizabad to Lucknow and built various monuments in and around Lucknow, including the Bara Imambara.

Architectural and other contribution

Asfi mosque, named after the Nawab, Asaf-ud-Daula.

Asfi mosque, named after the Nawab, Asaf-ud-Daula.

Nawab Asaf-ud-Dowlah is considered the architect general of Lucknow. With the ambition to outshine the splendour of Mughal architecture, he built a number of monuments and developed the city of Lucknow into an architectural marvel. Several of the buildings survive today, including the famed Asafi Imambara which attracts tourists even today, and the Qaisar Bagh area of downtown Lucknow where thousands live in resurrected buildings.

The Asafi Imambara is a famed vaulted structure surrounded by beautiful gardens, which the Nawab started as a charitable project to generate employment during the famine of 1784. In that famine even the nobles were reduced to penury. It is said that Nawab Asaf employed over 20,000 people for the project (including commoners and noblemen), which was neither a masjid nor a mausoleum (contrary to the popular contemporary norms of buildings). The Nawab's sensitivity towards preserving the reputation of the upper class is demonstrated in the story of the construction of Imambara. During daytime, common citizens employed on the project would construct the building. On the night of every fourth day, the noble and upper-class people were employed in secret to demolish the structure built, an effort for which they received payment. Thus their dignity was preserved.

The Nawab became so famous for his generosity that it is still a well-known saying in Lucknow that "he who does not receive (livelihood) from the Ali-Moula, will receive it from Asaf-ud-Doula" (Jisko na de Moula, usko de Asaf-ud-Doula).

Rumi Darwaza (Turkish Gate)

The Rumi Darwaza, which stands sixty feet tall,[7] was modeled (1784) after the Sublime Porte (Bab-iHümayun) in Istanbul, is one of the very important examples of the exchange between the two cultures.[8]

Death

He died on 21 September 1797 in Lucknow and is buried at Bara Imambara, Lucknow.

Gallery

Bara Imambara, Lucknow, built by Asaf-ud-Daula

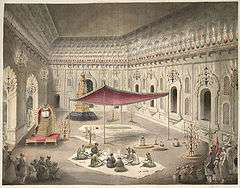

Bara Imambara, Lucknow, built by Asaf-ud-Daula A view of the Palace of the Asaf-ud-Daula at Lucknow, c.1793

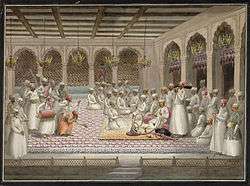

A view of the Palace of the Asaf-ud-Daula at Lucknow, c.1793 Asaf-ud-Daula, celebrating the Muharram festival at Lucknow, c.1812

Asaf-ud-Daula, celebrating the Muharram festival at Lucknow, c.1812 A silver ashrafi issued by Asaf-ud-Daula from the Najibabad mint in AH 1211 (1796/7), regnal year 38

A silver ashrafi issued by Asaf-ud-Daula from the Najibabad mint in AH 1211 (1796/7), regnal year 38 A silver ashrafi issued by Asaf-ud-Daula from the Najibabad mint in AH 1211 (1796/7), regnal year 38

A silver ashrafi issued by Asaf-ud-Daula from the Najibabad mint in AH 1211 (1796/7), regnal year 38 Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula seated on a rug smoking a hookah and listening to a party of male musicians, c.1812

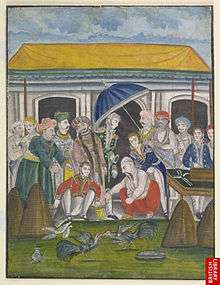

Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula seated on a rug smoking a hookah and listening to a party of male musicians, c.1812 Asaf-ud-Daula at a cock-fight with Europeans; this painting most likely depicts the famous cockfight between Asaf al-Daula and Colonel Mordaunt which took place at Lucknow in 1786, c.1830-35

Asaf-ud-Daula at a cock-fight with Europeans; this painting most likely depicts the famous cockfight between Asaf al-Daula and Colonel Mordaunt which took place at Lucknow in 1786, c.1830-35

Timeline

| Preceded by Jalal ad-Din Shoja` ad-Dowla Haydar |

Wazir al-Mamalik of Oudh 1775 – 1797 |

Succeeded by Mirza Wazir `Ali Khan |

See also

Notes

- title after death

References

- "Indian Princely States A-J".

- "Full text of "Oudh And The East India Company"".

- Chancey, Karen (2007). "Rethinking the Reign of Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab of Awadh, 1775-1797". Journal of Asian History. 1 (41): 1–56. JSTOR 41925390.

-

- Basu, P. (1938). The relations between Oudh and the East India Company from 1785 to 1801 (Ph.D.). University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies.

- "RCT - Zoffany, Portrait Drawing of Asaf-ud-Daula".

- "Rumi Darwaza".

- "Lucknow". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

External links

- NIC Website

- Refer to mapsofindia.com Bara Imambara for details of the Imambara

- HISTORY OF AWADH (Oudh) a princely State of India by Hameed Akhtar Siddiqui

- States before 1947 A-J