Art Instruction Schools

Art Instruction Schools, better known to many as Art Instruction, Inc., was a home study correspondence course providing training in cartooning and illustration.[1] The company was located in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Formerly | Federal School of Applied Cartooning |

|---|---|

| Industry | Education |

| Genre | Art |

| Founded | 1914 |

| Founder | Joseph Almars |

| Defunct | 2018 |

| Headquarters | Minneapolis, Minnesota |

Key people | Joseph Almars, Charles Lewis Bartholomew, Mort Walker, Charles M. Schulz |

| Website | ArtInstructionSchools.edu |

History

The school was founded as the Federal School of Applied Cartooning in 1914 as a branch of the Bureau of Engraving, Inc., to train illustrators for both the growing printing industry and the Bureau itself. Artists who received this training through these home study courses entered the fields of newspapers, printing and advertising.[1] Joseph Almars (1884–1948), who was born in Minneapolis, was both the vice president of the Bureau of Engraving and the president of Art Instruction, Inc.[2] In 2016, the school announced it would not be enrolling new students. The school closed at the end of 2018. [3]

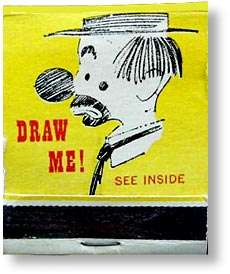

Draw Me!

Art Instruction, Inc. was known to many aspiring artists as the Draw Me! School, because of the familiar "Talent Test" advertising campaigns seen in magazine ads, matchbook covers with Spunky the Donkey, TV commercials and online promotions with the "Draw Me!" ad copy.[1][4][5]

As the company grew in popularity, it added instruction in cartooning, color, comics, composition, perspective and graphic design. The Fundamentals of Art course expanded to include all popular art techniques and contributions from Jay Norwood Darling, Charles M. Russell, Gaar Williams, wildlife artist Walter J. Wilwerding and cartoonist Frank Wing. The 12 textbooks also included contributions from J. C. Leyendecker, Charles Dana Gibson, Neysa McMein, Daniel Smith, A. B. Frost, John T. McCutcheon, Charles H. Sykes and Clare Briggs, plus illustrations by Maxfield Parrish, Russell Patterson, Franklin Booth, John La Gatta, Harry Townsend and Fontaine Fox.

Almars and Federal School dean Charles Lewis Bartholomew were the editors of the course. Born in Charlton, Iowa, Bartholomew studied under Burt Harwood and Douglas Volk. Primarily a children's books illustrator, he drew newspaper strips: Cousin Bill (1909), George and his Conscience (1907), Bud Smith, the Boy Who Does Stunts (1908–12), Alexander the Cat (1910) and Mama's Girl-Daddy's Boy.

Two of the school's instructors were cartoonist Mort Walker and Minneapolis native Charles M. Schulz (later of Peanuts fame). When Schulz was in high school, his mother saw an ad for the Art Instruction, Inc. talent test that asked, “Do you like to draw?” Schulz took the $170 course, a huge sum during the Depression, while his father labored to make the payments. After World War II, Schulz worked on Catholic comic magazines and then signed on as an instructor with Art Instruction, Inc. He was still employed there when he began sketching the characters that later were developed into Peanuts.[6] Several of the Peanuts characters, including Charlie Brown, Linus, Frieda and "the little red-haired girl" were based on Schulz' co-workers and friends at Art Instruction. Other instructors who were friends of Schulz included Louise Cassidy and Jim Sasseville. Louise Cassidy was the basis for the character of Aunty Climax in a short-lived comic strip by Jim Sasseville. In a 1994 address, Schulz said, "Art Instruction Inc., it was a wonderful place to get started because the atmosphere was not unlike that of a newspaper office. All the instructors were very bright people; they were all ambitious, each of them had his or her desire whether it was to be a fashion artist, or a cartoonist, or a painter."[7]

Other famed alumni include the illustrator John Clymer, comic strip artist Morrie Turner (Wee Pals) and Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Steve Benson. The school later capitalized on Clymer's fame with a textbook titled The Technique of J. Clymer.

Textbooks used in the 1940s and 1950s were edited by the cartoonist-illustrator Coulton Waugh, who drew the Dickie Dare comic strip. In addition to its softcover textbooks (one for each subject in the art field), Art Instruction, Inc. also had its own magazine, The Illustrator, published quarterly to showcase outstanding student work. By 1950, the fee for the course had increased to $300. When the company received "Draw me" submissions, these were turned over to salesmen who drove from one town to another, often arriving at a home unannounced and launching into a sales pitch.

In 1957-60, students received these 26 books by Wilwerding and others: Practical Lettering, Animal Drawing, Children and Animal Portraiture, Advertising Layout, Landscape & Seascape in Oil, Still life Techniques, Composition, Outline Drawing, Perspective, Wash and Beginning Color, Color Harmony, Portrait painting in Oil, Still Life in Oil, Painting Techniques, Commercial Art Techniques, Decorative Design, Advertising Illustration, Basic Figure Drawing, Fashion Illustration, Magazine Illustrating, Reproduction Processes, General Illustrating, Ink Drawing, Proportions and Shading, The Human Figure and The Technique of J. Clymer.

Methods

Despite advances in digital art, Art Instruction Schools continued to follow the teaching traditions it established over a century ago.[8]

In 2008, Art Instruction Schools used television commercials to reach prospective students.

See also

References

- Art Instruction Schools: "Our History"

- University of Minnesota: Lindstrom and Almars Collection

- ""Frequently Asked Questions"". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- Meier, Peg. "Draw Me," Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 18, 2002.

- McGrath, Charles. "Good Grief!" The New York Times Sunday Book Review, October 14, 2007.

- Virtues for Life Archived June 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ""Charles M. Schulz on Cartooning," Hogan's Alley #1, 1994". Archived from the original on 2015-06-03. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- Chin, Richard. "Drawn In," St. Paul Pioneer Press, December 10, 2000.