Armstrong Kessler Mansion (Savannah, Georgia)

The Armstrong Mansion is a nationally significant example of Italian Renaissance Revival architectural style located in the Savannah Historic District. The structure was built between 1917 and 1919 for the home of Savannah magnate George Ferguson Armstrong (1868–1924). It was owned by the Armstrong family from 1919 to 1935. Afterward, the structure and grounds served as the campus of Armstrong Junior College. Threatened with demolition, the Historic Savannah Foundation purchased the Armstrong House along with five other threatened historic buildings from the College for $235,000 in 1967. Once saved, Historic Savannah Foundation then sold the Mansion (and Hershel V. Jenkins Hall) at the exact purchase price to preservationist and antique dealer Jim Williams who restored it as his home. Eventually, both were sold to a major Savannah law firm as offices. The mansion was featured in The American Architect in 1919, and listed in A Field Guide to American Houses in 1984.

George Ferguson Armstrong

Armstrong was chief executive of Strachan Shipping Company, Savannah Marine Brokers; president of the Mutual Mining Company, extractors and shippers of Florida phosphate; and a director of the Hibernia Bank and of the Commercial Life Insurance and Casualty Company. He was a member of the Oglethorpe Club and the Savannah Cotton Exchange. In 1935, widow Lucy Camp Armstrong Moltz and daughter Lucy Armstrong Johnson donated the property for the campus of Armstrong Junior College at the request of the City of Savannah.[1][2]

Location and site

The Armstrong Kessler Mansion is located in Savannah’s National Historic Landmark District at 447 Bull Street across from Forsyth Park. It is in Monterey Ward (the center of which is Monterey Square), one of twenty-four wards laid out in the form of James Oglethorpe’s original town plan. Other notable structures on Bull Street in Monterey Ward are the Mercer House and Temple Mickve Israel. Six city lots were acquired to build the Armstrong mansion, and two existing houses were demolished to make room for the 26,000 square foot structure. The entire site, including carriage house and grounds, is 0.5 acres.

Original design

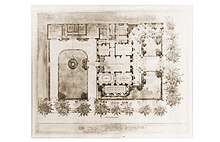

The mansion was designed by the architect Henrik Wallin (1873-1936) in 1917 in an Italian Renaissance Revival style with interior elements of various established and experimental styles. The ten-bedroom home has nearly 26,000 square feet of living area. It is three stories over a full garden level with Granite balustraded terraces at each level. A broad hemicycle colonnade extending toward Bull Street offers a prospect of Forsyth Park. Other design features include a porte-cochère that opens into a side garden, an orangery, loggia, and sunporch. Exterior materials are granite and glazed brick. Bronze entry doors were fabricated by Bonachek of New York, with other doors in steel with bronze hardware. Windows were fabricated of steel and bronze by International Casement Company, now Hope Windows, which features the home in their promotional materials.[3][4][5]

The attached carriage house was also three stories, having two garage bays designed for automobiles with front and rear entrances from the street or from the alley (or “lane” as they are called in Savannah). Living quarters were between and above the garages. The street entrances thus approached the carriage house through the garden creating a circular drive, with one side passing through the porte-cochere.[6]

The landscape plan consisted of two formal yards on either side of a wide graduated approach to the front entrance, orchestrated to match the grandeur of the main hall. The effect in front carried through to the rear, where a second entrance under the porte-cochere faced a large rear garden. Front and rear grounds were enclosed with 200 feet of ornate iron fencing resembling that of Buckingham Palace.[7]

Interior design

The main hall was designed with Italian limestone claddings with ornate plaster ceilings and cornices. Floor-length windows, cornices, panels, friezes, and details reflecting a range of styles are found throughout the interior. Rooms drew from various period styles including Georgian, Adamesque, Jacobean, and even Arts and Crafts. The house was fully electrified, and had a central vacuum system, recirculating hot water, and a ten port shower in the master bathroom.[8][9]

Modifications

With the acquisition of the Armstrong mansion in 1935 for the home of a city college, initially named Armstrong Junior College, the need for facilities led to the demolition of most of the carriage house and gardens and construction of Herschel V. Jenkins Hall, also designed by Henrik Wallin. When the property became the offices of the law firm of Bouhan, Williams & Levy in 1970, Herschel V. Jenkins Hall was demolished to make room for parking. Numerous non-structural modifications were made throughout to accommodate the law practice. With the restoration of the property begun in 2017 (see below), the gardens and a portion of the carriage house has been recreated.[10]

In popular culture

The Armstrong Kessler Mansion setting has appeared frequently in popular culture. The house was used as the school of the daughter of the protagonist in Cape Fear, the 1962 psychological thriller starring Robert Mitchum, Gregory Peck, Martin Balsam, and Polly Bergen. The house also appeared as the real-life law office of attorney Sonny Seiler in the film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, a 1997 American crime drama film based on the novel by John Berendt and directed by Clint Eastwood.[11]

Restoration

The present owner, the preservationist-hotelier Richard C. Kessler, who acquired the mansion in 2017, commissioned a complete restoration of the Armstrong property. The structure, interior, and Italianate landscape are being restored as closely as possible to the original design with original materials. The architect and urban designer Christian Sottile developed the master plan for restoration. Interiors have been carried out by the designer Chuck Chewning. The plan includes a two-story recreation of the carriage house and the addition of a reflecting pool centered on the carriage house. The porte-cochere, carriage house, and garden pavilion frame a formal garden with fountains and Italian cypresses.[12]

Notes

- Nussbaum, “A century of Savannah history.”

- Stone, From the Mansion to the University, 7, 15.

- McAlester and McAlester, A Field Guide, 406, Figure 6.

- “House of George F. Armstrong,” The American Architect, Plates 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51.

- Sottile, “Armstrong Kessler Mansion” video documentation.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- McAlester and McAlester, A Field Guide, 406.

- Sottile, “Armstrong Kessler Mansion” video documentation.

- Nussbaum, “A century of Savannah history.”

- Kigar, “Houses with History”; “Savannah Scenes: Cape Fear (1962)”.

- Sottile, “Armstrong Mansion” video documentation.

Bibliography

- “House of George F. Armstrong, Savannah, Georgia.” The American Architect. Vol. CXVI, No. 2276, August 6, 1919.

- Kigar, Taylor. “Houses with History.” Savannah.com. Posted on August 15, 2014 http://www.savannah.com/houses-with-history/

- McAlester, Virginia and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to American Houses. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

- Nussbaum, Katie. “A century of Savannah history: Richard Kessler returning Armstrong mansion to residential roots.” Savannah Morning News online, February 3, 2018. https://www.savannahnow.com/news/2018-02-03/century-savannah-history-richard-kessler-returning-armstrong-mansion-residential (accessed March 1, 2019).

- “Savannah Scenes: Cape Fear (1962).” Bonnie Blue Tours Blog. https://www.bonniebluetours.com/blog/2013/09/04/savannah-scenes-1-cape-fear-1962 (accessed March 5, 2019).

- Sottile, Christian. “Armstrong Kessler Mansion - Renovation of A Savannah Icon.” Video documentation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nwefrBGL70c (accessed March 5, 2019).

- Stone, Janet D. From the Mansion to the University: A History of Armstrong Atlantic State University 1935-2010. Savannah, Ga.: Armstrong Atlantic State University, 2010.

External links

- Armstrong Kessler Mansion history and restoration video documentation - YouTube, June 6, 2018