Arctic haze

Arctic haze is the phenomenon of a visible reddish-brown springtime haze in the atmosphere at high latitudes in the Arctic due to anthropogenic[1] air pollution. A major distinguishing factor of Arctic haze is the ability of its chemical ingredients to persist in the atmosphere for significantly longer than other pollutants. Due to limited amounts of snow, rain, or turbulent air to displace pollutants from the polar air mass in spring, Arctic haze can linger for more than a month in the northern atmosphere.

History

Arctic haze was first noticed in 1750 when the Industrial Revolution began. Explorers and whalers could not figure out where the foggy layer was coming from. "Poo-jok" was the term the Inuit used for it.[2] Another hint towards clarifying this issue was relayed in notes approximately a century ago by Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen. After trekking through the Arctic he found dark stains on the ice.[3] The term "Arctic haze" was coined in 1956 by J. Murray Mitchell, a US Air Force officer stationed in Alaska,[4] to describe an unusual reduction in visibility observed by North American weather reconnaissance planes. From his investigations, Mitchell thought the haze had come from industrial areas in Europe and China. He went on to become an eminent climatologist.[5] The haze is seasonal, reaching a peak in late winter and spring. When an aircraft is within a layer of Arctic haze, pilots report that horizontal visibility can drop to one tenth that of normally clear sky. At this time it was unknown whether the haze was natural or was formed by pollutants.

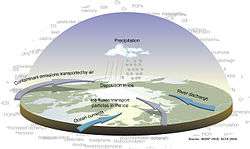

In 1972, Glenn Shaw of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska attributed this smog to transboundary anthropogenic pollution, whereby the Arctic is the recipient of contaminants whose sources are thousands of miles away. Further research continues with the aim of understanding the impact of this pollution on global warming.[6]

Origin of pollutants

Coal-burning in northern mid-latitudes contribute aerosols containing about 90% sulfur and the remainder carbon, that makes the haze reddish in color. This pollution is helping the Arctic warm up faster than any other region, although increases in greenhouse gases are the main driver of this climatic change.[7]

Sulfur aerosols in the atmosphere affect cloud formation, leading to localized cooling effects over industrialized regions due to increased reflection of sunlight, which masks the opposite effect of trapped warmth beneath the cloud cover. During the Arctic winter, however, there is no sunlight to reflect. In the absence of this cooling effect, the dominant effect of changes to Arctic clouds is an increased trapping of infrared radiation from the surface.

Ship emissions, mercury, aluminium, vanadium, manganese, and aerosol and ozone pollutants are many examples of the pollution that is affecting this atmosphere, but the smoke from forest fires is not a significant contributor.[8] Some of those pollutants figure among environmental effects of coal burning. Due to low deposition rates, these pollutants are not yet having adverse effects on people or animals. Different pollutants actually represent different colors of haze. Dr. Shaw discovered in 1976 that the yellowish haze is from dust storms in China and Mongolia. The particles were carried polewards by unusual air currents. The trapped particles were dark gray the next year he took a sample. That was caused by a heavy amount of industrial pollutants.[3]

A 2013 study found that at least 40% of the black carbon deposited in the Arctic originated from gas flares, predominately from oil extraction activities throughout the northern latitudes.[9][10] The black carbon is short-lived, but such routine flaring also emits vast quantities of sulphur. Home fires in India also contribute.[11]

Recent studies

According to Tim Garrett, an assistant professor of meteorology at the University of Utah involved in the study of Arctic haze at the university, mid-latitude cities contribute pollution to the Arctic, and it mixes with thin clouds, allowing them to trap heat more easily. Garret's study found that during the dark Arctic winter, when there is no precipitation to wash out pollution, the effects are strongest, because pollutants can warm the environment up to three degrees Fahrenheit.[12]

Scientific predictions

European climatologists predicted in 2009 that by the end of the 21st century, the temperature of the Arctic region is expected to rise 3° Celsius on an average day.[13] In that same article, National Geographic quoted the co-author of the study, Andreas Stohl, of the Norwegian Institute for Air Research, "Previous climate models have suggested that the Arctic's summer sea ice may completely disappear by 2040 if warming continues unabated."

See also

Footnotes

- Shaw, Glenn E. (December 1995). <2403:TAHP>2.0.CO;2 "The Arctic Haze Phenomenon". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 76 (12): 2403–2413. Bibcode:1995BAMS...76.2403S. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1995)076<2403:TAHP>2.0.CO;2.

- Garrett, Tim. Pollutant Haze is Heating up the Arctic. 10 May 2006. Earth Observatory. Earth Observatory News Archived 2 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Soroos, Marvin. The odyssey of Arctic haze: toward a global atmosphere regime. December, 1992. Environment Magazine". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- Rozell, Ned. "Arctic Haze: An Uninvited Spring Guest". 2 April 1996. Geographical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. 1 May 2007. Archived 12 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- McFadden, Robert D. (8 October 1990). "J. Murray Mitchell, Climatologist Who Foresaw Warming Peril, 62 - Page 2". New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "Contaminating the Arctic". Content.scholastic.com. 15 January 1995. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- Law, Kathy S.; Stohl, Andreas (16 March 2007). "Arctic Air Pollution: Origins and Impacts". Science. 315 (5818): 1537–1540. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1537L. doi:10.1126/science.1137695. PMID 17363665. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- "Previously some scientists had speculated that the sooty carbon in the arctic air was the product of natural forest fires, rather than industrial combustion. But a clever application of carbon isotope dating rules out that possibility," observes John Harte, The Green Fuse: an ecological odyssey 1993:19; fossil fuels are comparatively depleted in rare heavy carbon, which decays slowly to nitrogen, so that wildfire carbon is identifiable by its carbon fingerprint.

- Stohl, A.; Klimont, Z.; Eckhardt, S.; Kupiainen, K.; Chevchenko, V.P.; Kopeikin, V.M.; Novigatsky, A.N. (2013), "Black carbon in the Arctic: the underestimated role of gas flaring and residential combustion emissions", Atmos. Chem. Phys., 13 (17): 8833–8855, Bibcode:2013ACP....13.8833S, doi:10.5194/acp-13-8833-2013

- Michael Stanley (10 December 2018). "Gas flaring: An industry practice faces increasing global attention" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Lean, Geoffrey (3 April 2005). "Home Fires In India Melting Arctic Icecap". The Independent. London.

- Study: The Haze is Heating Up the Arctic. 10 May 2006. United Press International.

- "Summary report of " Arctic Climate Feedbacks: Global Implications" September 2009". Wwf.panda.org. 2 September 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

References

- Connelly, Joel. Pictures of Arctic are Hard to Argue With. 13 November 2006. Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- Rozell, Ned. Arctic Haze: An Uninvited Spring Guest. 2 April 1996. Geographical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. 1 May 2007

- Study: The Haze is Heating Up the Arctic. 10 May 2006. United Press International.

- Garrett, Tim. Pollutant Haze is Heating up the Arctic. 10 May 2006. Earth Observatory.

- Contaminating the Arctic. 1 January 1999. Scholastic.

- Gorrie, Peter. Grim prognosis for Earth. 3 January 2007. Toronto Star.