Argidava

Argidava (Argidaua, Arcidava, Arcidaua, Argedava, Argedauon, Argedabon, Sargedava, Sargedauon, Zargedava, Zargedauon, Ancient Greek: Ἀργίδαυα, Αργεδαυον, Αργεδαβον, Σαργεδαυον) was a Dacian fortress town close to the Danube, inhabited and governed by the Albocense. Located in today's Vărădia, Caraş-Severin County, Romania.

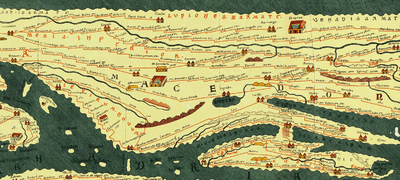

.svg.png) Arcidava on the Roman Dacia map. | |

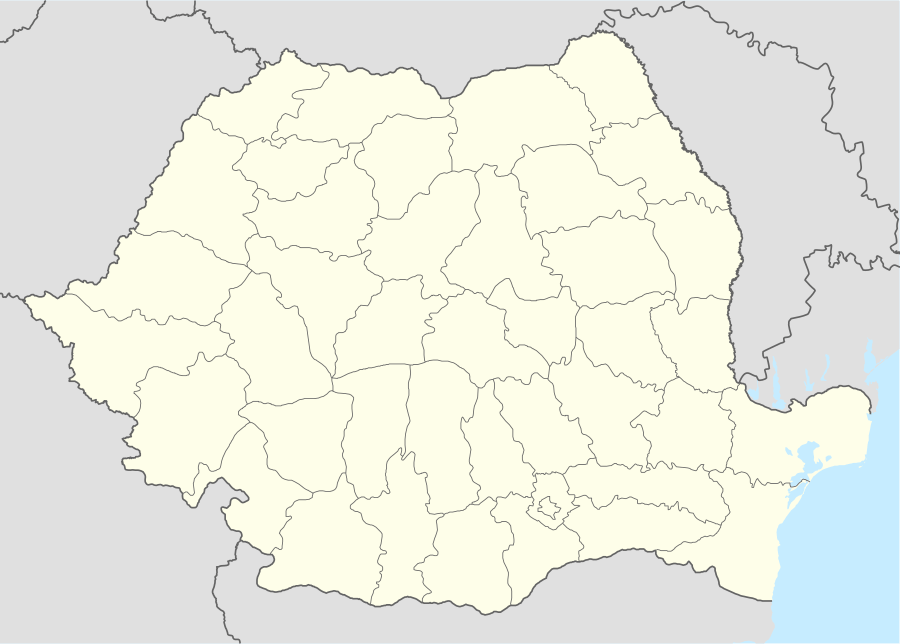

Shown within Romania | |

| Alternative name | Argidaua, Arcidava, Arcidaua, Argedava, Argedauon, Argedabon, Sargedava, Sargedauon, Zargedava, Zargedauon |

|---|---|

| Location | Poiana Flămânda,[1] Vărădia, Caraş-Severin County, Romania |

| Coordinates | 45.08°N 21.55°E |

| History | |

| Cultures | Albocense |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Reference no. | CS-I-s-B-10894 [1] |

After the Roman conquest of Dacia, it became a military and a civilian center, with a castrum (Roman fort) (see Castra Arcidava) built in the area. The fort was used to monitor the shores of the Danube.[2]

Ancient sources

The oldest found potential reference to Argidava is in the form Argedauon or Argedabon (Ancient Greek: Αργεδαυον, Αργεδαβον), written in stone, in the Decree of Dionysopolis (48 BC).[3][4] However, it is unclear as to whether this refers to Argidava or a distinct town Argedava.

Decree of Dionysopolis

This decree was written by the citizens of Dionysopolis to Akornion, who traveled far away in a diplomatic mission to meet somebody's father in Argedauon.[5]

The inscription also refers to the Dacian king Burebista, and one interpretation is that Akornion was his chief adviser (Ancient Greek: πρῶτοσφίλος, literally "first friend") in Dionysopolis.[6] Other sources indicate that Akornion was sent as an ambassador of Burebista to Pompey, to discuss an alliance against Julius Caesar.[7]

This leads to the assumption that the mentioned Argedava was Burebista's capital of the Dacian kingdom. This source unfortunately doesn't mention the location of Argedava and historians opinions are split in two groups.

One school of thought, led by historians Constantin Daicoviciu and Hadrian Daicoviciu, assumes that the inscription talks about Argidava and place the potential capital of Burebista at Vărădia, Caraş-Severin County, Romania. The forms Argidava and Arcidava found in other ancient sources like Ptolemy's Geographia (c. 150 AD) and Tabula Peutingeriana (2nd century AD), clearly place a Dacian town with those names at this geographical location. The site is also close to Sarmizegetusa, a later Dacian capital.

Others, led by historian Vasile Pârvan and professor Radu Vulpe place Argedava at Popeşti, Giurgiu County, Romania. Arguments include the name connection with the Argeş River, geographical position on a potential road to Dionysopolis which Akornion followed, and most importantly the size of the archaeological discovery at Popeşti that hints to a royal palace. However no other sources seem to name the dava discovered at Popeşti, so no exact assumptions can be made about its Dacian name.

It is possible that the two different davae are homonyms.

The marble inscription is damaged in many areas, including right before the word Argedauon, and it is possible the original word could have been Sargedauon (Ancient Greek: Σαργεδαυον) or Zargedauon. This form could be linked to Zargidaua mentioned by Ptolemy at a different geographical location. Or, they could be homonyms.

The decree, a fragmentary marble inscription, is located in the National Museum in Sofia.

Ptolemy's Geographia

Argidava is mentioned in Ptolemy's Geographia (c. 150 AD) in the form Argidaua (Ancient Greek: Ἀργίδαυα) as an important Dacian town, at latitude 46° 30' N and longitude 45° 15' E (note that he used a different meridian and some of his calculations were off).

Tabula Peutingeriana

Argidava is also depicted in the Tabula Peutingeriana (2nd century AD) in the form Arcidaua, on a Roman road network, between Apo Fl. and Centum Putea. The location corresponds to the one mentioned by Ptolemy and the different form is most likely caused by the G/C graphical confusion commonly found in Latin documents.[8]

Notes

- "National Archaeological Record (RAN)". ran.cimec.ro. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Grumeza, Ion. Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe. Lanham: Hamilton Books, 2009, p. 13, ISBN 978-0-7618-4465-5.

- Mihailov 1970.

- Daicoviciu 1972, p. 90.

- Crisan 1978, p. 61.

- Daicoviciu 1972, p. 127.

- Oltean 2007, p. 47.

- Olteanu.

References

- Crisan, Ion Horatiu (1978). "Burebista and His Time". Bucharest: Bibliotheca Historica Romaniae. Missing or empty

|url=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Daicoviciu, Hadrian (1972). "Dacii". Bucharest: Editura Enciclopedica Româna. Missing or empty

|url=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Mihailov, Georgi (1970). "Inscriptiones graecae in Bulgaria repertae" (in Latin and Greek). 1 (2nd ed.). Sofia: In aedibus typographicis Academiae Litterarum Bulgaricae. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Oltean, Ioana Adina (2007). Dacia: landscape, colonisation and romanisation. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-41252-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olteanu, Sorin. "Linguae Thraco-Daco-Moesorum - Toponyms Section". Linguae Thraco-Daco-Moesorum (in Romanian and English). Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dacia and Dacians. |

- Ptolemy's Geography at LacusCurtius – Book III, Chapter 8 Location of Dacia (from the Ninth Map of Europe) (English translation, incomplete)

- Sorin Olteanu's Project: Linguae Thraco-Daco-Moesorum – Toponyms Section

- A fost Argedava (Popesti) resedinta statului geto-dac condus de Burebista? – Article in Informatia de Giurgiu (Romanian)

- Searchable Greek Inscriptions at The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) – Argedava segment from Decree of Dionysopolis reviewed in Inscriptiones graecae in Bulgaria repertae by Georgi Mihailov