Antoine André de Sainte-Marthe

Antoine André, chevalier de Sainte-Marthe de Lalande (1615 – 12 August 1679) was a French soldier who served in England, Belgium and Martinique. He is best known for his defeat of the Dutch in their attempted Invasion of Martinique (1674). As a young man he served as a captain of the guard of Queen Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I of England. After the 1646 defeat of the royalists in the English Civil War he joined the French service and fought in Flanders against the Spanish until the conclusion of peace in 1659. After spending some time unemployed or with a peacetime garrison he joined the king's guard in 1667, and this led to his appointment as governor of Martinique from 1672 until his death in 1679.

Antoine André, chevalier de Sainte-Marthe de Lalande | |

|---|---|

| Governor of Martinique | |

| In office 28 December 1672 – December 1679 | |

| Preceded by | Robert de Clodoré François Rolle de Laubière (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Jacques de Chambly |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1615 Richelieu, Indre-et-Loire, France |

| Died | 12 August 1679 Fort-de-France, Martinique |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Soldier |

Family

The Sainte-Marthe family originated in Poitou, became prominent in the reign of king Charles VII of France (1422–1461) and produced many distinguished writers including Scévole de Sainte-Marthe and his sons.[1] Antoine André, chevalier de Sainte-Marthe, was born in 1615 in the chateau de Braslou, Richelieu, Indre-et-Loire. His parents were René de Sainte-Marthe, Seigneur de la Lande (1587–1632) and Marguerite Razin de La Verdonnerie.[1] His paternal grandfather was Scévole's brother Louis de Sainte-Marthe, chevalier, seigneur de Boisvre and lieutenant-general of Poitou.[1]

England

Sainte-Marthe left home to avoid being forced into a marriage he did not want, spent some time in La Rochelle and then the Île de Ré, then moved to London.[2] He reached London around January 1641, where he met César, Duke of Vendôme, Bernard de Nogaret de La Valette d'Épernon and Charles de La Vieuville, who had also left France due to the hostility of Cardinal Richelieu.[3] In the company of the three exiled French dukes Sainte-Marthe was introduced to the entourage of Queen Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV of France and wife of Charles I of England. There he met Marguerite Ested, one of the queens maids of honour, from an aristocratic family of Lancaster. He won her hand and the position of captain in the guards regiment in 1641, where he served under Prince Rupert of the Rhine, who had come from Holland to serve under his uncle Charles I and had been named head of the king's armies.[4] During the First English Civil War (1642–1646) Rupert led the royalist forces until the capitulation at Oxford on 23 January 1647, when his army was dissolved and he had to leave for France.[4]

Flanders War

Prince Rupert accepted a well paid commission from Anne of Austria to serve Louis XIV of France as a mareschal de camp on condition that he could leave French service to fight for King Charles I of England if called upon to do so.[5] He brought with him many loyal officers, including Saint-Marthe, and some soldiers, and formed a regiment with these troops.[6] Sainte-Marthe's wife was near term with her second child, and had to wait until it was delivered before rejoining him after five months.[4] In all they had one daughter and three sons.[7]

Sainte-Marthe returned to France at the start of the war in Flanders when the Franco-Spanish War continued after the Thirty Years' War was formally concluded by the Peace of Westphalia.[6] Sainte-Marthe took a post in Rupert's regiment as capitaine aide-major (adjutant), and participated in the campaigns of 1647 and 1648 until the fall of Ypres in Belgium. At this time Rupert's regiment was dissolved and incorporated into the regiment of the English colonel Thomas de Rokeby. Saint-Marthe served under Rokeby in the campaign of 1649 at Cambrai and Condé. Rokeby returned to England under the command of Rupert, handing over his regiment to Victor-Maurice de Broglie, governor of La Bassée in Flanders. Saint-Marthe continued as capitaine aide-major under de Broglie in the campaigns of 1654–57 until the Treaty of the Pyrenees was concluded on 7 November 1659.[6] His first wife died in La Bassée in 1658, leaving him with four children.[7]

Later career

In 1660 Saint-Marthe's daughter Alison married Jean-Baptiste de la Haye des Aublois, an officer he had come to know during the last siege of Ypres. Sainte-Marthe next took a job as captain of the La Fère regiment, which was in winter quarters at Saint-Venant in Normandy, and held this position from 1664 to 1665, when company was dissolved. The regiment was led by colonel Jacob Blanquet de la Haye(fr).[8] He then settled near Saint-Pol in Artois, and married Isabelle-Louise du Riez de Willerval, daughter of the seigneur of Averdoingt.[6][7] They had two sons and six daughters.[7] Through the influence of the count de Charost and of his relative M. Carnavelet, both captains in the kings guard, he entered that service in 1667.[8] The same sponsors recommended him to the minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who appointed him governor of Martinque on 1 July 1672.[9]

Martinique

Sainte-Marthe was governor of Martinique from 1672 to 1679.[7] He took his wife and six children with him, and arrived in Saint Pierre on 28 December 1672.[10] The governor-general of the Antilles, Jean-Charles de Baas, was not at first enthusiastic about the idea of a governor who was a complete stranger to the colony.[10] However, in a letter to Colbert of 1 June 1673 he wrote that Sainte-Marthe had done his duty well, and was active and intelligent. He asked that Saint-Marthe be given some other source of income, because what the company paid would only meet half his needs. De Baas went on to complain about the excessive prices of food sent from France. This inclined the people towards the Dutch, who had always treated them well.[11] This last note referred to a royal ordinance of 10 June 1670 that had banned all trading between the French colonies in the Americas and foreign countries.[12]

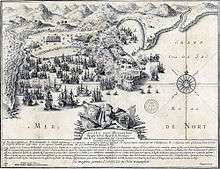

The Third Anglo-Dutch War was launched by the English and French in 1672, but the allies were outmatched by the Dutch forces under Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, who inflicted several defeats.[13] After the English had withdrawn from their alliance with France against the Dutch, on 16 July 1674 de Ruyter appeared off Martinique with a fleet that included 18 warships, support vessels and 15 troop transports with 3,400 soldiers. The French were expecting de Ruyter but thought Fort Royal (now Fort-de-France) was impregnable, so had concentrated their forces up the coast at Saint Pierre. De Ruyter directed his force to Fort Royal, but was becalmed on the first day, giving the French time for urgent efforts to improve the defenses.[14]

Saint Marthe arrived to take command at dawn, by which time the French had booms across the harbour mouth and enough men to work the batteries.[15] Two armed ship were anchored off the fort: the 44-gun royal frigate Jeux and the 22-gun merchantman Saint Eustache.[16] At the start of the attempted Invasion of Martinique de Ruyter's force was greeted by heavy gunfire when it entered the harbour in the morning on 20 July. 1,000 Dutch troops were landed at 9:00 a.m. but found themselves trapped below high cliffs, exposed to fire from the French batteries and from the two armed ships. They broke into a rum warehouse and all discipline was lost. The Dutch troops escaped by boat around 1:00 a.m., made a second assault at 2:00 p.m., and again were forced to retreat. The Dutch had lost 143 dead and 318 wounded against 15 French dead. They abandoned the effort, sailed north that night, and eventually returned to Europe in disarray.[15]

The king ennobled Sainte-Marthe for his victory against the Dutch. De Baas, who had been jealous of Sainte-Marthe, died on 15 January 1677 leaving Sainte-Marthe in sole charge for almost a year. On 19 April 1678 the king sent him gift of 3,000 silver livres for his good administration. He died on 12 August 1679 and was replaced on 7 June 1680. His family remained in Martinique where they played a prominent role in the later history of the colony.[17]

Notes

- Guët 1893, p. 140.

- Guët 1893, pp. 141–143.

- Guët 1893, p. 143.

- Guët 1893, p. 144.

- Spencer 2007, p. 180.

- Longuemare 1902, p. 195.

- Roux.

- Guët 1893, p. 145.

- Guët 1893, pp. 145–146.

- Guët 1893, p. 146.

- Guët 1893, p. 147.

- Guët 1893, p. 148.

- Rickard 2000.

- Marley 1998, p. 178.

- Marley 1998, p. 179.

- Marley 1998, pp. 178–179.

- Guët 1893, p. 164.

Sources

- Guët, Isidore (1893), Origines de la Martinique. Le colonel François de Collart et la Martinique de son temps; colonisation, sièges, révoltes et combats de 1625 à1720, Vannes: Lafolye, retrieved 2018-08-27

- Longuemare, Paul de (1902), Une Famille D'auteurs (in French), Paris: Slatkine, GGKEY:PHR6D96XQS1, retrieved 2018-08-26

- Marley, David (1998), Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-87436-837-6, retrieved 2018-08-26

- Rickard, J. (12 December 2000), "Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674)", History of War, retrieved 2018-08-24

- Roux, Sophie de, "Antoine André de SAINTE-MARTHE", Geneanet (in French), retrieved 2018-08-26

- Spencer, Charles (2007), Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier, London: Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-297-84610-9