Antimary State Forest

The Antimary State Forest (Portuguese: Floresta Estadual do Antimary) is a state forest in the state of Acre, Brazil. It was the first state forest in Acre, established with the goal of understanding and implementing sustainable forest exploitation, including extraction of nuts and rubber as well as selective extraction of timber. It has been extensively studied and discussed internationally as a model of sustainable forest management.

| Antimary State Forest | |

|---|---|

| Floresta Estadual do Antimary | |

| |

| Nearest city | Bujari, Acre |

| Coordinates | 9.42975°S 68.0671°W |

| Area | 47,064 hectares (116,300 acres) |

| Designation | State forest |

| Created | 7 February 1997 |

| Administrator | Fundação de Tecnologia do Estado do Acre |

Location

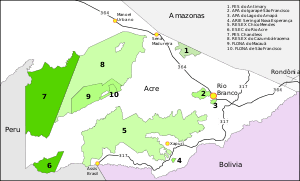

1: Antimary State Forest

The Antimary State Forest is divided between the municipalities of Sena Madureira (26.94%) and Bujari (73.06%) in the eastern part of the state of Acre.[1] It is north of the BR-364 highway, and is bounded by the border with the state of Amazonas to the northeast.[2] It has an area of 47,064 hectares (116,300 acres).[1]

Environment

Average annual temperatures are 25 °C (77 °F). The land is relatively flat, with maximum elevation of about 300 metres (980 ft) above sea level. Soils are mainly dystrophic yellow latosols with high clay content. Annual rainfall is about 2,000 millimetres (79 in). The dry season from June to September is used for slash-and-burn land clearance for agriculture and for forest management and logging.[3] Satellite images show that the forest is:[4]

- 21.5% open rainforest with palms and dense alluvial rainforest with uniform canopy

- 15.8% open lowland rainforest with dominant bamboo

- 30.2% open rainforest with bamboo and dense lowland rainforest with emergent canopy

- 12.0% dense lowland rainforest with emergent canopy and open rainforest with dominant bamboo

- 19.5% dense lowland rainforest with emergent canopy

The most common flora are from the Caesalpinaceae, Mimosaceae, Moraceae, Fabaceae and Euphorbiaceae families. The State of Acre Technology Foundation (FUNTAC) has identified 625 species of flora including 361 of trees and 18 of palm trees. There are 114.5 trees per hectare on average, with an average basal area of 15.23 square metres (163.9 sq ft) per hectare and an estimated volume with bark of 128.98 cubic metres (4,555 cu ft) per hectare.[4]

Background

The Antimary River is first mentioned in a 1907 letter by José Plácido de Castro on navigation of the Acre River. He described the main geographical points of the Antimary, a tributary of the Acre.[5] He noted that there were several shacks on the river banks, indicating the presence of rubber tappers.[6] The area of the forest was declared a reserve on 26 June 1911, but nothing more was done at the time.[7][8] Before Antimary State Forest was created there were 80–100 families living in the forest. Most of the population were rubber tappers, and most come from Acre. About 28% come from other states, particularly Ceará.[5]

The Antimary State Forest Project was created in 1988 by decree 8.843, the first such in Acre.[9] It was a joint project of the state government and the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) with focus on gaining basic information on the forest's physical aspects, flora, fauna, people and land use. By the 1990s studies were considering sustainable use of multiple forest resources, economic feasibility and issues of forestry concessions.[4] Despite the value of non-timber products to the local population and the economy, timber was considered to be the product with the greatest economic potential.[7]

History

The forest was formally defined by state governor decree 046 of 7 February 1997, which created a forest with an area of 66,168 hectares (163,500 acres) from the Pacatuba, Arapixi and Canari II seringais (rubber extraction areas).[6] It has become one of the most studied public forests in the world. In 2002 it was chosen by ITTO as one of the three best examples of forests funded by that organisation. It was presented as a side event at Earth Summit 2002 (Rio + 10).[10] In 2004 the forest received certification by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) for timber management on 77,000 hectares (190,000 acres), of which 66,000 hectares (160,000 acres) were for enterprises and 11,000 hectares (27,000 acres) for community management.[11] Other than trials in 2003 and 2004, as of 2005 no formal logging had been undertaken.[12] The consultative council was created on 31 December 2004.[13]

Various adjustments were made to the original area, with land added in 1998 and land lost to the state of Amazonas by a boundary adjustment. By 2005 the forest had an area of 83,807 hectares (207,090 acres) with boundaries very different from the original.[6] In 2005 the forest received certification from the Rainforest Alliance's SmartWood Program.[14] Ordnance 19 of 22 June 2005 redefined the forest boundaries to include the Pacatuba, Arapixi and Novo Amparo lands, giving it an area of 65,965 hectares (163,000 acres). The managed area included 62,656.68 hectares (154,828.0 acres) of natural or semi-natural forest, of which 53,456.34 hectares (132,093.5 acres) were assigned to timber production.[15]

Decree 13321 of 1 December 2005 amended the forest's limits to contain 47,064 hectares (116,300 acres).[13] On 13 December 2005 the Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform) recognised the forest as an agro-extractive project for 250 families, who would now qualify for assistance under PRONAF (National Program for the Strengthening of Family Farming).[13]

The forest is valuable as a research site. The state of Acre funds ten graduate and undergraduate students to research forest management and forest product processing in Antimary.[8] A study published in 2012 reported results of estimating above-ground biomass (AGB) and identifying low-intensity logging areas in the forest using airborne scanning lidar. Scans were made of two unlogged areas in the forest and one with low-intensity selective logging. A model-assisted estimator and synthetic estimator both gave accurate measures of the amount of biomass that had been removed, as confirmed by ground-based checks.[16] Even when the residual canopy remained closed, the lidar could identify harvest areas, roads, skid trails and landings, and the reduction of biomass that had resulted.[3]

People and economy

The state of Acre coordinates management through the Acre State Forests Department (SEF), working with businesses, communities and technical advisers of the State of Acre Technology Foundation (FUNTAC) and Amazon Workers Center (CTA).[11] In 2003 an area of 2,200 hectares (5,400 acres) was managed, with a gross volume of 16,713 cubic metres (590,200 cu ft) of wood extracted. The cut intensity was 7.6 cubic metres (270 cu ft) per hectare, or less than two trees per hectare.[17] There were two forest engineers and eight technicians.[18]

By 2003 the forest was inhabited by 109 families with 383 people, mainly rubber tappers, organised into two associations and one cooperative. Their main income came from extraction of Brazil nuts (100 tonnes) and rubber (12 tonnes), followed by copaiba oil (260 litres), forest seeds (1,270 kilograms).[19] Each family has the right to use (but not to sell) an area of 300 to 400 hectares (740 to 990 acres) of forest, roughly the area in which a family would have tapped rubber trees.[8] They also engage in subsistence agriculture and timber extraction.[5] In the rainy season the Antimary River is the only transport route for families living in the state forest, used for carrying Brazil nuts, rubber and cassava flour.[20] The project headquarters in 2003 had an access road, lodgings and telephone service. There were four health centres. 90% of the residents had been vaccinated and there had been no malaria cases for three years.[21] Both adults and children enrolled in three schools, and illiteracy had dropped from 90% to 15%.[22]

The proportion of processed wood products coming from managed forests in Acre grew from 5.7% in 2002 to 84% in 2008. By 2008 forestry accounted for 19% of Acre's economy and half the state's exports by value. The Antimary State Forest was still the only certified public forest in Brazil.[23] There were mixed feeling about the shift to timber extraction among the residents of the Acre forests, with many still remembering their struggle to preserve the forests as extractivists and rubber tappers against loggers and ranchers from other states, while some accepted timber management as a way to gain more from the forest, despite the rigorous certification rules.[23]

Notes

- FES do Antimary – ISA, Informações gerais.

- FES do Antimary – ISA, Informações gerais (mapa).

- d'Oliveira et al. 2012, p. 480.

- Resumo Público de Certificação ... SmartWood, p. 5.

- FES do Antimary – ISA, Características.

- Resumo Público de Certificação ... SmartWood, p. 6.

- Santos Aquino, Viana de Lima & Gama e Silva 2011, p. 105.

- Hamilton 2006.

- Santos Aquino, Viana de Lima & Gama e Silva 2011, p. 104.

- Santos Aquino, Viana de Lima & Gama e Silva 2011, p. 112.

- Santos Aquino, Viana de Lima & Gama e Silva 2011, p. 106.

- Resumo Público de Certificação ... SmartWood, p. 5–6.

- FES do Antimary – ISA, Histórico Jurídico.

- Resumo Público de Certificação ... SmartWood, p. 1.

- Resumo Público de Certificação ... SmartWood, p. 7.

- d'Oliveira et al. 2012, p. 479.

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável ... ITTO, p. 12.

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável ... ITTO, p. 11.

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável ... ITTO, p. 6.

- Terezinha Moreira 2012.

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável ... ITTO, p. 7.

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável ... ITTO, p. 8.

- Vadjunec & Schmink 2014, p. 88.

Sources

- Desenvolvimento Florestal Sustentável na Amazônia Brasileira Projeto PD 94/90 Projeto PD 94/90 (in Portuguese), ITTO, retrieved 2016-07-02

- d'Oliveira, Marcus V.N.; Reutebuch, Stephen E.; McGaughey, Robert J.; Andersen, Hans-Erik (2012), "Estimating forest biomass and identifying low-intensity logging areas using airborne scanning lidar in Antimary State Forest, Acre State, Western Brazilian Amazon." (PDF), Remote Sensing of Environment, 124, retrieved 2016-07-02

- FES do Antimary (in Portuguese), ISA:Instituto Socioambiental, retrieved 2016-07-02

- Hamilton, Roger (1 January 2006), Could environmentalists learn to love this road?, Inter-American Development Bank, retrieved 2016-07-02

- Resumo Público de Certificação de FLORESTA ESTADUAL DO ANTIMARY (PDF) (in Portuguese), SmartWood Program, 21 October 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2008, retrieved 2016-07-02

- Santos Aquino, Maria Lúcia R.; Viana de Lima, Eduardo Rodrigues; Gama e Silva, Zenobio Abel Gouvêa Perelli da (July–December 2011), "Manejo madeireiro na floresta estadual do Antimary, estado do Acre, Brasil", Revista Nera, Presidente Prudente, 14 (19), ISSN 1806-6755, retrieved 2016-07-02

- Terezinha Moreira (28 August 2012), "Governo inicia limpeza do Rio Antimary", Notícias do Acre (in Portuguese), retrieved 2016-07-02

- Vadjunec, Jacqueline M.; Schmink, Marianne (2014-07-16), Amazonian Geographies: Emerging Identities and Landscapes, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-98297-5, retrieved 2016-07-02