Anterior spinal veins

Anterior spinal veins (also known as anterior coronal veins and anterior median spinal veins) are veins that receive blood from the anterior spinal cord.

| Anterior spinal veins | |

|---|---|

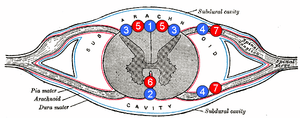

1: Posterior spinal vein 2: Anterior spinal vein 3: Posterolateral spinal vein 4: Radicular (or segmental medullary) vein 5: Posterior spinal arteries 6: Anterior spinal artery 7: Radicular (or segmental medullary) artery | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Anterior spinal artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Venae spinales anteriores |

| TA | A12.3.07.024 |

| FMA | 70892 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

There are two major components to venous draining: the intrinsic vessels which drain first, and the pial veins which drain second. Within the intrinsic vessels are a group of veins known as central veins. These are organized into individual comb-like repetitive structures that eventually fuse together once in the ventral median spinal fissure. After their fusion the group of central veins drains its combined contents into an anterior spinal vein.[1] These veins can infiltrate back into the ventral median spinal fissure previously mentioned by up to a few centimeters. They are also not only smaller in size but more numerous than the equivalent anterior spinal artery which they lie dorsal to.

There are three anterior spinal veins in total. These, along with three posterior spinal veins, are allowed to communicate with one another as they run interconnected throughout the entire length of the spinal cord. This is seen through both sets of veins combining to form a network of anastomoses around the conus medullaris. Together, these two sets of veins also collect blood from intramedullary radial veins as well as other veins. They are drained by the anterior and posterior radicular veins, respectably. Radicular veins appear blue to the naked eye. Next, both radicular veins travel to the epidural space by means of joining the internal vertebral venous plexuses. Ultimately, this plexus is able to send and receive information from the veins and sinuses inside the brain. The external vertebral venous plexuses is also available for the internal vertebral venous plexus to communicate with.[2]

Anterior spinal veins fall into the intradural network of the vertebral venous system. The intradural network breaks down into the intramedullary and extramedullary systems which are sets of highly reliable veins. This is because they are vastly redundant in what they do and so only fail under exceedingly unfavorable conditions. Their dependability can be compromised, however, by the bridge that connects them. This fragile link across the dura mater of the spine is known as the radiculomedullary veins. Although these veins connect the trustworthy intramedullary and extramedullary veins, they have no support network to protect them and are seen in much fewer numbers by comparison. This may lead to complications such as thrombosis. For example patients that have spinal dural fistulas can experience venous hypertension caused by thrombosis of these veins.[3]

Function

The anterior spinal cord, which makes up 2/3 of the entire spinal cord, gets its blood supply from the anterior spinal artery. This artery in turn receives its blood from the different radiculospinal branches, which are formed from the aorta and vertebral arteries. As the largest of the radiculospinal artery branches, the Artery of Adamkiewicz provides a large amount of blood to the anterior spinal artery, thereby also supplying a good amount to the anterior spinal cord.

Research

There is a very limited availability to research the spinal venous system as a whole, which in turn leads to an even smaller availability to research the anterior spinal veins. This lack of research is due in great majority to the fact that there is no reliable method of visualizing the system in a noninvasive manner. Although some methods such as an MRI can give off useful information, these stationary glimpses do not show the true actions that take place. The most efficient way to study the spinal venous system along with the anterior spinal veins is to do it postmortem. These types of studies give an effective anatomical demonstration of how the system works. One of the few major studies of the venous anatomy was conducted by Armin Thron, which can be seen in his published “Vascular Anatomy of the Spinal Cord” from 1988.

References

- Fischer, Georges, and Jacques Brotchi. Intermedullary Spinal Cord Tumors. 2. 1. Paris, France: Masson, 1996. 9. eBook. <https://books.google.com/books?id=TL21lTxABxUC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0

- Lin VW, Cardenas DD, Cutter NC, et al., editors. Spinal Cord Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2003. Blood Supply of the Spinal Cord. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8851/

- Shapiro, Dr. Maksim. "Spinal Venous Anatomy." Neuroangio. WordPress, n.d. Web. 7 Nov 2012. <http://neuroangio.org/spinal-vascular-anatomy/spinal-venous-anatomy/>.