Anne Knight

Anne Knight (2 November 1786 – 4 November 1862)[1] was an English social reformer, abolitionist and pioneer of feminism. She attended the 1840 Anti-Slavery convention, where the need to improve women's rights became obvious.[1] In 1847 Knight produced what is thought to be the first leaflet for women's suffrage and formed the first UK women's suffrage organisation in Sheffield in 1851.

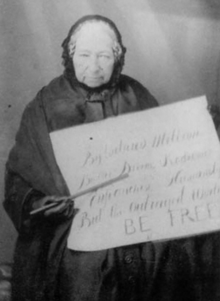

Anne Knight | |

|---|---|

"By tortured millions, By the divine redeemer, Enfranchise Humanity, Bid the Outraged World, BE FREE" | |

| Born | 2 November 1786 Chelmsford, England |

| Died | 4 November 1862 Waldersbach, France |

| Nationality | British |

Family background

Anne Knight was born in Chelmsford in 1786. She the daughter of William Knight (1756–1814), a Chelmsford grocer, and his wife Priscilla Allen (1753–1829). Her parents’ families were both Quakers and several of their members took an active part in the temperance and anti-slavery movements.[1]

Early efforts and frustrations

In 1825 she was a member of the Chelmsford Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society when she toured Europe with a group of Quakers. The tour was part sightseeing but also took in good causes. Knight could speak in both French and German.[1]

Knight worked closely with other leading abolitionists: Thomas Clarkson, Elizabeth Pease and Joseph Sturge.

When women were prevented from participating in the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, Knight was outraged and started to campaign for women's rights. A few women were included in the painting of the convention with Knight; these were Elizabeth Pease, Amelia Opie, Baroness Byron, Mary Anne Rawson, Mrs John Beaumont, Elizabeth Tredgold, Thomas Clarkson's daughter-in-law and niece Mary and right at the back Lucretia Mott.[2]

In 1847 Knight produced what is considered the first leaflet for women's suffrage. Her efforts to impress the importance of women's suffrage on such reform leaders as Henry Brougham and Richard Cobden proved of little use, as did her efforts with the Chartist leadership.[1]

Knight was described by the American Quaker Lucretia Mott in the 1840s as "a singular looking woman – very pleasant and polite."[3]

Move to France

She moved to France in 1846 and participated in the revolution of 1848, and attended the international peace conference in Paris in 1849. With Jeanne Deroin she challenged the banning of women from political clubs and of publication of feminist material. In 1851, she worked with Anne Kent to form the Sheffield Female Political Association, the first British organisation to call for women's suffrage.[1]

Death and commemorations

Anne Knight never married. She died at Waldersbach, near Strasbourg, France, on 4 November 1862, at the house of the grandson of Jean-Frédéric Oberlin (1740–1820), a philanthropist whose work she revered.

A village, Knightsville in Jamaica, was named after her, or possibly after her younger sister Maria (1791–1870), who visited the West Indies in the mid-1810s with the abolitionist John Candler (1787–1869).

Some of the new student accommodation at the University of Essex, Anne Knight House, is named after her. So also is Anne Knight House, opened in January 2005 by the Colchester Quaker Housing Association a hostel for young people. A Grade II listed building opposite the railway station in Chelmsford, her birthplace, used as a Quaker Meeting House from 1823 until the 1950s, was named Anne Knight Building in her honour. It formed part of the Anglia Ruskin University central campus until this was relocated in 2008. The building was subsequently vacant until 2015 when it enjoyed a brief period of use as a cultural project before being turned into a family-owned chain restaurant.

References

- Edward H. Milligan: Knight, Anne (1786–1862). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: OUP, 2004) Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, accessed 19 July 2008

- Edward H. Milligan: Knight, Anne (1786–1862).... Quoting F. B. Tolles, ed.: Slavery and 'the Woman Question' (London: Journal of the Friends Historical Society Supplement, 1952), p. 29.