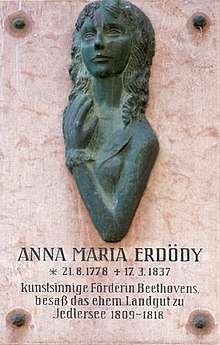

Anna Maria Erdődy

Countess Anna Maria (Marie) von Erdődy (8 September 1779 – 17 March 1837) was a Hungarian noblewoman and among the closest confidantes and friends of Ludwig van Beethoven. Dedicatee of four of the composer's late chamber works, she was instrumental in securing Beethoven an annuity from members of the Austrian high nobility.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Life

She was born Countess von Niczky in Arad, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, today Romania. On June 6, 1796, she married Count Péter Erdődy of Monyorokerék and Monte Claudio, scion of the noted Erdődy line of the Hungarian/Croatian aristocracy.[1][7] They had two daughters and a son: Marie, Friederike, and August, affectionately known as Mimi, Fritzi, and Gusti.[5] On May 3, 1798, Anna Maria was honoured by induction into the imperial Order of the Starry Cross.[1] In 1805 she became estranged from Count Péter through desertion[2] and eventually settled into a ménage with Johann Xaver Brauchle (1783–1838), her long-serving secretary and children's music teacher, who later became a composer.[2][8][1] From 1815 she lived in Paucovec in Croatia, subsequently in Padua. In December 1823, for political outspokenness, she was expelled from Austria and moved to Munich where she died.[2][1]

Association with Beethoven

Marie Erdődy became one of the great supporters of Beethoven from the early years of the 19th century. She was often in his company and they became friends and confidants, Beethoven referring to Marie as his "father confessor".[4] Their association can be dated from as early as 1802, the year of the Heiligenstadt Testament, during which difficult time Beethoven made frequent visits to Jedlesee—one mile from Heiligenstadt and five miles north of Vienna—where Marie had inherited the small country estate which today houses the Vienna-Floridsdorf Beethoven Memorial.[2] Thayer writes, "It is not at all improbable that the vicinity of the Erdödy estate at Jedlesee am Marchfeld was one reason for his frequent choice of summer lodgings in the villages on the Danube, north of the city".[3] In October 1808, Beethoven left the Pasqualati House, where he had lived for four years, and moved one block down into the Countess's large apartment on the Krugerstraße, No. 1074, residing there with Marie until March 1809.[9][3][10]

Marie was instrumental in helping to sway members of the Imperial nobility to granting Beethoven a lifelong annuity in an effort to induce him to remain in Austrian lands in the face of an offer of employment as Kapellmeister in Cassel, from Jérôme, King of Westphalia. Jan Swafford characterizes Beethoven's real intentions thus:

But by now he knew he would probably not go to Cassel, if he ever actually wanted to in the first place. Instead, he was busily involved in plans to secure a permanent annuity from a collection of Viennese patrons. The idea, and the outline of the agreement, had originated with Beethoven himself and had been promoted by Baron Gleichenstein and Countess Erdödy. Its gist was that in return for staying in Vienna, Beethoven asked to receive a yearly sum simply for plying his trade as he saw fit. The amount he hoped to receive was roughly the same as he had been offered in Cassel.[10]

Thayer states, "It seems likely that the suggestion that formal stipulations for a contract be drawn up under which Beethoven would decline the offer from Cassel and remain in Vienna came from the Countess Erdödy."[3] "The Countess Erdödy is of the opinion that you ought to outline a plan with her," wrote Beethoven to Gleichenstein early in 1809, "according to which she might negotiate in case they[11] approach her, which she is convinced they will... If you should have time this afternoon, the Countess would be glad to see you."[3][4] Negotiations resulted in Beethoven signing a contract with princes Lobkowitz, Kinsky and the Archduke Rudolf (in which they promised to pay him a regular stipend for life), his rejection of the Cassel post, and his remaining in Vienna until his death in 1827.[9][10][12]

In gratitude for these services and her hospitality in the years 1808 through 1809, Beethoven dedicated to Marie Erdődy the two piano trios opus 70, composed during Beethoven's extended stay with her, and later the pair of cello sonatas opus 102, written for the cellist Joseph Linke (who, along with Brauchle, became a tutor to Marie's children[5]), and the canon Glück zum neuen Jahr (Happy New Year), WoO 176, of 1819.[5][6]

"Immortal Beloved" candidacy

In her second biographical study of the composer,[2] Beethoven scholar Gail S. Altman investigates Maynard Solomon's claims for the identity of the woman who Beethoven, in an undated letter found among his effects, called his "Immortal Beloved" (Unsterbliche Geliebte). Altman builds a thorough case—using Solomon's own criteria—for Anna Maria Erdődy as the preferred putative recipient of the letter.[9][2] Questioning Solomon's attribution of the place-initial "K", in the Immortal Beloved letter, to Karlsbad, she offers in its place the hypothesis that "K" might instead refer to Klosterneuburg, then the closest post-stop to Marie Erdödy's estate at Jedlesee and to her summer residence at Hernals, Klosterneuburg's neighbouring villages north of Vienna,[13] it being documented how familiar the couple had grown since at least the year 1808, and noting Marie's 1805 separation from her husband.[14][2] Altman's ascription of "K" to Klosterneuburg has been rejected by at least one writer on logistical grounds: citing the alleged absence of crossings yet apparently unaware that in summer 1812, as Altman makes clear, Marie was at Hernals on the west bank of the Danube,[2] Barry Cooper questions Altman's Klosterneuburg attribution on the basis of Jedlesee lying across the river from it.[15] As Altman says in summing up, Beethoven visited Hernals in September 1812, "and therefore saw his Beloved as he had indicated he would in his letter to her", adding that, wherever Beethoven expected to be at the time he wrote the letter was where the Beloved would have been, both to receive the letter and to reunite with him.[2]

Notes

- Robert Münster: "Anna Maria Gräfin Erdödy" in Johannes Fischer (ed.): Münchener Beethoven-Studien. Katzbichler, München 1992, ISBN 3-87397-421-5, pp. 217–224.

- Gail S. Altman Beethoven: A Man of His Word – Undisclosed Evidence for his Immortal Beloved, Anubian Press 1996; ISBN 1-888071-01-X

- Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Thayer's Life of Beethoven (Hermann Deiters, Henry Edward Krehbiel, Hugo Riemann, Editors, G. Schirmer, Inc., New York, 1921).

- Emily Anderson, Editor, The Letters of Beethoven, vol. 1 (London, Macmillan Press, 1986, 3 Volumes).

- Barry Cooper, Beethoven (Master Musicians, 2008, Oxford University Press)

- "Beethoven" by Joseph Kerman and Alan Tyson in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Stanley Sadie, 2001)

- "Das Testament der Gräfin Maria Erdödy, geb. Niczky", Erich Krapf and Rudolf Hösch (eds.), in: Festschrift anläßlich des zehnjährigen Bestandes des "Vereines der Freunde der Beethoven-Gedenkstätte in Floridsdorf", Vienna 1981, p. 27 ff.)

- Günther Haupt, "Gräfin Erdödy und J. X. Brauchle", in: Der Bär. Jahrbuch von Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1927, pp. 70–99.

- Maynard Solomon, Beethoven (1977, 1998, 2001, Schirmer Books).

- Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (Houghton Mifflin, Harcourt, 2014).

- The princes Kinsky, Lobkowitz and the Archduke Rudolf.

- Alexander Wheelock Thayer in A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (George Grove, Editor, 1900).

- Google (28 January 2019). "Klosterneuburg, Hernals, Jedlesee – relative positions." (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Alfred Schöne, Briefe von Beethoven an Marie Gräfin Erdödy, geb. Gräfin Niszky, und Mag. Brauchle, Leipzig 1867 digitized at Google Books

- Barry Cooper (1996): "Beethoven’s Immortal Beloved and Countess Erdödy: A Case of Mistaken Identity?", Beethoven Journal XI/2, pp. 18–24.

Further reading

- Dana Steichen, Beethoven's Beloved (New York, 1959)