Elephant goad

The elephant goad, bullhook, or ankus (from Sanskrit aṅkuśa or ankusha) is a tool employed by mahout in the handling and training of elephants. It consists of a hook (usually bronze or steel) which is attached to a 60–90 cm (2.0–3.0 ft) handle, ending in a tapered end.

A relief at Sanchi and a fresco at the Ajanta Caves depict a three-person crew on the war elephant, the driver with an elephant goad, what appears to be a noble warrior behind the driver and another attendant on the posterior of the elephant.[1] Nossov and Dennis (2008 p 19) report that two perfectly preserved elephant goads were recovered from an archaeological site at Taxila and are dated from 3rd century BCE to the 1st century CE according to Marshall. The larger of the two is 65 cm long.[1]

Nossov and Dennis (2008: p. 16) state:

An ankusha, a sharpened goad with a pointed hook, was the main tool for managing an elephant. The ankusha first appeared in India in the 6th-5th century BC and has been used ever since, not only there, but wherever elephants served man.[2]

Fabrication and construction

The handle can be made of any material, from wood to ivory, depending on the wealth and opulence of the owner. Contemporary bullhooks which are used for animal handling generally have handles made of fibreglass, metal, plastic, or wood.

The elephant goad is found in armouries and temples all across India, where elephants march in religious processions and perform in various civil capacities. They are often quite ornate, being decorated with gemstones and engravings to be appropriate for the ceremonies in which they are used.

Iconography

The elephant goad is a polysemic iconographic ritual tool in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, in the inclusive rubric of Dharmic Traditions.

The elephant has appeared in cultures across the world. They are a symbol of wisdom in Asian cultures and are famed for their memory and intelligence, where they are thought to be on par with cetaceans[3] and hominids.[4] Aristotle once said the elephant was "the beast which passeth all others in wit and mind".[5] The word "elephant" has its origins in the Greek ἐλέφας, meaning "ivory" or "elephant".[6]

In iconography and ceremonial ritual tools, the elephant goad is often included in a hybridized tool, for example one that includes elements of Vajrakila, 'hooked knife' or 'skin flail' (Tibetan: gri-gug, Sanskrit: kartika), Vajra and Axe, as well as the goad functionality for example. Ritual Ankusha were often finely wrought of precious metals and even fabricated from ivory, often encrusted with jewels. In Dharmic Traditions the goad/ankusha and rope 'noose/snare/lasso' (Sanskrit: Pāśa) are traditionally paired as tools of subjugation.[7]

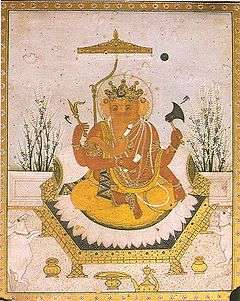

Hinduism

In the Hinduism, an elephant goad is one of the eight auspicious objects known as Ashtamangala and certain other religions of the Indian subcontinent. A goad is also an attribute of many Hindu gods, especially Tripura Sundari & Ganesha.

Buddhism

Wallace and Goleman (2006: p. 79) discuss 'śamatha' (Sanskrit), mindfulness and introspection which they tie to metacognition:

Throughout Buddhist literature, the training in shamatha is often likened to training a wild elephant, and the two primary instruments for this are the tether of mindfulness and the goad of introspection.[8][9]

Rowlands (2001: p. 124) in discussing consciousness and its self-conscious, self-reflexive quality of apperception states that:

The most significant aspect of consciousness, I shall try to show, is its structure, its hybrid character. Consciousness can be both act and object of experience. Using the somewhat metaphorical notion of directing, we might say that consciousness is not only the directing of awareness but can be that upon which awareness is directed. Consciousness is not only the act of conscious experience, it can be experience's object. [italics preserved from original][10]

In the above quotation the metaphor of 'directing' is employed. In 'directing' consciousness or the mind to introspectively apperceive the directive forded by the goad is key.

Tattvasamgraha Tantra

In the Tattvasamgraha tantra (c 7th century), one of the most important tantras of the Buddhist Yoga Tantra Class, the ankusha figures in the visualization of one of the retinue. This tantra explains the process of the visualization of the Vajradhatu Mandala, which is one of the most visually stylized of Buddhist mandalas. The Ankusha is the symbolic attribute for the visualization of the Bodhisattva Vajraraja, an emanation within the retinue of Vajradhatu. This visualization is treated in Tachikawa (c2000: p. 237).[11]

Literature

In Rudyard Kipling's Second Jungle Book story "The King's Ankus", Mowgli finds the magnificently-jeweled elephant goad of the title in a hidden treasure chamber. Not realizing the value men place on jewels, he later casually discards it in the jungle, unwittingly leading to a chain of greed and murder amongst those who find it after him.

References

- Nossov, Konstantin & Dennis, Peter (2008). War Elephants. illustrated by Peter Dennis. Edition: illustrated. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-268-7 (accessed: Monday April 13, 2009), p.18

- Nossov, Konstantin & Dennis, Peter (2008). War Elephants. illustrated by Peter Dennis. Edition: illustrated. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-268-7 (accessed: Monday April 13, 2009), p.16

- "What Makes Dolphins So Smart?". Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- "Cognitive behaviour in Asian elephants: use and modification of branches for fly switching". BBC. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- O'Connell, Caitlin (2007). The Elephant's Secret Sense: The Hidden Lives of the Wild Herds of Africa. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 174, 184. ISBN 978-0-7432-8441-7.

- Soanes, Catherine; Angus Stevenson (2006). Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-929634-0.

- Beer, Robert (2003). The handbook of Tibetan Buddhist symbols. Serindia Publications, Inc. Source: (accessed: Sunday April 12, 2009), p.146

- Wallace, B. Alan with Goleman, Daniel (2006). The Attention Revolution: Unlocking the Power of the Focused Mind. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-276-5. Source: (accessed: Sunday April 14, 2009) p.79

- Wallace & Goleman (2006: p.79): "Buddhist psychology classifies introspection as a form of intelligence (prajna), and its development has long been an important element of Buddhist meditation. A similar mental faculty, usually called matacognition, is now coming under the scrutiny of modern psychologists. Cognitive researchers have defined metacognition as knowing of one's own cognitive and affective processes and states, as well as the ability to consciously and deliberately monitor and regulate those processes and states. This appears to be an especially rich area for collaborative research between Buddhist contemplatives and cognitive scientists." Source: (accessed: Sunday April 14, 2009)

- Rowlands, Mark (2001). The nature of consciousness. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80858-8. Source: (accessed: Sunday April 12, 2009), p.124

- Tachikawa, M. (c2000). 'Mandala visualization and possession'. New Horizons in Bon Studies. Source: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2009-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (accessed: Saturday October 31, 2009)

Further reading

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dallapiccola