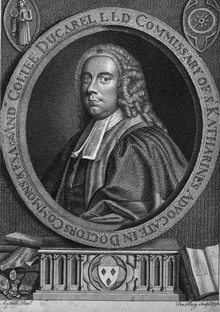

Andrew Ducarel

Andrew Coltée Ducarel (9 June 1713 – 29 May 1785), was an English antiquary, librarian, and archivist. He was also a lawyer practising civil law (a "civilian"), and a member of the College of Civilians.[1]

Early life and education

Ducarel was born on 9 June 1713 in Paris. His parents, Jacques Coltée Ducarel (1680–1718) and Jeanne Crommelin (1690–1723), were Huguenots from Normandy.[2] Jacques was a banker and merchant, who achieved ennoblement in 1713 with the title Marquis de Chateau de Muids.[3] He died in 1718, just as a new wave of Huguenot persecution was beginning, and in 1719 Jeanne fled with her three infant sons first to Amsterdam, and then, in 1721, to England. They settled in Greenwich, where Jeanne married her second husband, Jacques Girardot, another Huguenot.

In 1728 Andrew was sent to be educated at Eton. The following year he suffered a serious accident there in which he lost one eye: he spent three months under the medical care of Sir Hans Sloane. In 1731 he matriculated at Oxford from Trinity College, but transferred shortly afterwards to St John's. In 1734, while still undergraduates, he and his brother were naturalized.[2] Ducarel graduated in 1738 as a Bachelor of Civil Law, and then moved to Trinity Hall, Cambridge.[4] He was created Doctor of Civil Law in 1742, and "went out a grand compounder" on 21 October 1748.[5] He was admitted a member of the College of Advocates at Doctors' Commons 3 November 1743, and afterwards served as librarian there 1754–7, and as treasurer 1757–61.[2]

Legal and administrative career

Ducarel was appointed "commissary or official" (i.e. an ecclesiastical judge) of the royal peculiar of St Katharine's by the Tower by Archbishop Thomas Herring in 1755; of the city and diocese of Canterbury by Archbishop Thomas Secker in December 1758; and of the sub-deaneries of South Malling, Pagham, and Tarring in Sussex, by Archbishop Frederick Cornwallis, on the death of Dr. Dennis Clarke, in 1776.[2]

In 1756, on the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, he was appointed to the High Court of Admiralty to take depositions for prize ships.

Antiquarian, library and archival career

On 22 September 1737 Ducarel was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and he was one of the first fellows of the society nominated by the president and council on its incorporation in 1755. He was also elected a member of the Society of Antiquaries at Cortona on 29 August 1760, was admitted a fellow of the Royal Society of London on 18 February 1762, became an honorary fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Cassel in November 1778, and of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1781.

In 1755 he failed to obtain the post of sub-librarian at the British Museum; but in 1757 he was appointed keeper of Lambeth Palace Library by Archbishop Hutton. His predecessors in this post (who had included Henry Wharton, Edmund Gibson and David Wilkins) had all been clergymen who treated the post as a part-time responsibility and as a stepping-stone to more lucrative ecclesiastical preferments. Ducarel, by contrast, remained in post for nearly thirty years, under five archbishops (Herring, Hutton, Secker, Cornwallis, and Moore), until his death.[6]

He greatly improved the catalogues both of the printed books and the manuscripts at Lambeth, and made a digest, with a general index, of all the registers and records of the province of Canterbury.[7] He was assisted by his friend, Edward Rowe Mores, the Rev. Henry Hall (his predecessor in the office of librarian), and the engraver Benjamin Thomas Pouncy, who was for many years his clerk and deputy librarian. Ducarel's contribution was seriously impeded by his complete blindness in one eye, and the weakness of the other. Besides the digest preserved among the official archives at Lambeth, he formed another personal manuscript collection in forty-eight volumes: after his death this passed to the antiquary Richard Gough, and in 1810 was bought for the British Museum library.

He also took a more general interest in the ecclesiastical antiquities of the province of Canterbury, and, with Mores, compiled a history of Croydon Palace and of the town of Croydon. This was completed and presented to Archbishop Herring in manuscript in 1755, and published in 1783. However, the work led to a virulent rift between the two friends, when Mores, who had made significant contributions to it, discovered that he was not named on the title page.[2][8]

In 1763 Ducarel was appointed by the government, with Sir Joseph Ayloffe and Thomas Astle, to sort and catalogue the records of the state paper office at Whitehall, and afterwards those in the augmentation office.

On the death of Archbishop Secker in 1768 Ducarel applied for the post of secretary to the new archbishop, Frederick Cornwallis, but without success.

Wider antiquarianism

For many years Ducarel used to go in August on an antiquarian tour through different parts of the country, in company with his friend Samuel Gale, and attended by a coachman and footman. They travelled about fifteen miles a day, and put up at inns. After dinner, while Gale smoked his pipe, Ducarel transcribed his topographical and archaeological notes. In an engraving of London Bridge Chapel by George Vertue, the figure measuring is Ducarel, and that standing is Gale.[9]

In 1752, with a friend, Thomas Bever, he undertook a tour of Normandy. Through his publications Tour through Normandy in a letter to a Friend (1754), later greatly expanded and illustrated as Anglo-Norman Antiquities Considered (1767), he effectively put the Duchy on the map for the late 18th-century English traveller.[10] He was one of the first Englishmen to see and appreciate the significance of the Bayeux Tapestry, and included an account of it written by his late friend Smart Lethieullier – the first detailed description in English – as an appendix to Anglo-Norman Antiquities.

Character sketches

Francis Grose described Ducarel in scathing terms:

The Doctor was a very weak man, and ignorant, though he was ambitious of being thought learned. Among the many publications which bear his name, none were really written by him; most of them were done by Sir Joseph Ayloffe, and the Rev. Mr. Morant, author of the History of Essex; to whom the Doctor applied on every emergency. He was so very illiterate, that on receiving a Latin letter from a foreign university, he took his chariot, and went down to Colchester, where Mr. Morant then lived, and got him to write an answer.[11]

Grose further wrote:

The Doctor was a large black man,[12] with only one eye, and that of a focus not exceeding half an inch; so that whatever he wished to see distinctly he was obliged to put close to his nose. ... [He] always was a great lover of the ladies as well as his glass; the latter grew on him so much, that he was constantly drunk every day, a little before his death: his liquor was generally port, or as he called it, "kill priest".[13]

Horace Walpole similarly formed a negative opinion of him:

Dr. Ducarel was a poor creature. He was keeper of the library at Lambeth; and I wanted a copy of that limning there, which is prefixed to my Royal and Noble Authors. Applying to the Doctor, I found nothing but delays. I must purchase his works, and take some of his antiques at an exorbitant price, &c. Completely disgusted, I applied to the Archbishop himself, who immediately permitted a drawing to be taken.[14]

According to John Nichols, who knew him well:

Though he never ate meat till he was 14, nor drank till he was 18, yet it was a maxim which he religiously observed that as Ducarel himself often maintained, "he was an old Oxonian, and therefore never knew a man till he had drunk a bottle of wine with him." His entertainments were in the true style of the old English hospitality; and he was remarkably happy in assorting the company he not infrequently invited to his table.[15]

Death and legacy

Ducarel was a fit and athletic man, who believed that he would live to a great age.[16] The immediate cause of his final illness was the shock of receiving a letter at Canterbury informing him that his wife was at the point of death. He hurried home to South Lambeth, took to his bed, and died three days later, on 29 May 1785. He was buried on the north side of the altar in the church of St Katharine's by the Tower. In the event, Mrs Ducarel survived him more than six years, dying on 6 October 1791.[17]

His coins, pictures, and antiquities were sold by auction on 30 November 1785, and his books, manuscripts, and prints in April 1786. The greater part of the manuscripts passed into the hands of Richard Gough and John Nichols.

Personal life

In 1749 Ducarel married Sarah Desborough (1696–1791). She was a widow seventeen years his senior, who had previously been his housekeeper.[2] He is said to have married her out of gratitude, after being nursed by her through a severe illness. In Grose's view, these circumstances "tended greatly to his future establishment, Mrs. Ducarrel being a sober, careful woman".[13] There were no children of the marriage.

Works

- A Tour through Normandy, described in a letter to a friend (anon.) (London, 1754); republished in a greatly enlarged form (and under Ducarel's name) as Anglo-Norman Antiquities considered, in a Tour through part of Normandy, illustrated with 27 copperplates (London, 1767)

- De Registris Lambethanis Dissertatiuncula (London, 1766)

- A Series of above 200 Anglo-Gallic, or Norman and Aquitain Coins of the antient Kings of England (London, 1757)

- Some Account of Browne Willis, Esq., LL.D. (London, 1760)

- A Repertory of the Endowments of Vicarages in the Diocese of Canterbury (London, 1763; 2nd edn, 1782)

- A Letter to William Watson, M.D., upon the early Cultivation of Botany in England; and some particulars about John Tradescant, gardener to Charles I (London, 1773); appeared originally in Philosophical Transactions, vol. 63, p. 79

- Account of William Stukeley, in vol. 2 of Stukeley's Itinerary (1776)

- A List of various Editions of the Bible, and parts thereof, in English; from the year 1526 to 1776 (London, 1776) (enlarged from a manuscript originally prepared by Joseph Ames)

- Some Account of the Alien Priories, and of such lands as they are known to have possessed in England and Wales, collected by John Warburton, Somerset Herald, and Ducarel, 2 vols (London, 1779; 2nd edn 1786)

- History of the Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St. Katharine, near the Tower of London (1782)

- Some Account of the Town, Church, and Archiepiscopal Palace of Croydon (1783) [written with Edward Rowe Mores]

- History and Antiquities of the Archiepiscopal Palace of Lambeth (1785); in Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, vol. 2

References

- This specialized form of law was used in certain jurisdictions in England, including the royal peculiar of St Katharine's by the Tower, and in Anglican ecclesiastical courts.

- Myers 2008.

- Jones-Baker 1995, p. 330.

- "Du Carel, Andrew Coltee (CRL739AC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Nichols 1812, p. 380.

- Slatter 1957, p. 97.

- Slatter 1957.

- Myers 1999, pp. 200-204.

- Nichols 1812, p. 402.

- Myers 1996.

- Grose 1792, p. 140.

- i.e. dark and swarthy.

- Grose 1792, p. 142.

- Walpole, Horace (1799). Walpoliana. 1. London: R. Phillips. p. 73.

- Nichols 1812, p. 404.

- Nichols 1812, pp. 402-3.

- The Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 61.2 (1791), p. 973

References from DNB

![]()

- William Thomas Lowndes's Bibliographer's Manual (Bohn), p. 680

- John Cave-Browne, Lambeth Palace and its associations (1883), preface, pp. ix, xi, 66-8, 105, 106

Bibliography

- Grose, Francis (1792). The Olio. London. pp. 139–42.

- Jones-Baker, Doris Whipple (1995). "A Huguenot scholar, antiquary, and Lambeth Palace Librarian, Andrew Coltée Ducarel, 1713–85". Proceedings of the Huguenot Society. 26: 330–41.

- Lisle, Gerard de; Myers, Robin, eds. (2019). Two Huguenot Brothers: letters of Andrew and James Coltée Ducarel 1732–1773. London: Garendon Press. ISBN 9781527237223.

- Myers, Robin (1996). "Dr Andrew Coltée Ducarel (1713–1785), pioneer of Anglo-Norman studies". In Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael (eds.). Antiquaries, Book Collectors and the Circles of Learning. Winchester: St Paul's Bibliographies. pp. 45–70. ISBN 1-873040-29-6.

- Myers, Robin (1999). "Dr Andrew Coltée Ducarel, Lambeth Librarian, Civilian, and Keeper of the Public Records". The Library. 6th ser. 21: 199–222. doi:10.1093/library/s6-21.3.199.

- Myers, Robin (2008) [2004]. "Ducarel, Andrew Coltée (1713–1785)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8126. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Myers, Robin (2018). "Dr Ducarel and his books: was André Coltée Ducarel a bibliomaniac?". The Library. 19 (2): 203–25.

- Nichols, John (1812). "Dr. Andrew Ducarel". Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century; comprizing biographical memoirs of W. Bowyer, and many of his learned friends. 6. London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley. pp. 380–405.

- Slatter, M. D. (1957). "A. C. Ducarel and the Lambeth MSS". Archives. 3: 97–104.

External links

- Works by or about Andrew Ducarel in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- entry for Andrew Ducarel at the Royal society