Andrea Bowers

Andrea Bowers (born 1965) is a Los Angeles-based American artist working in a variety of media including video, drawing, and installation. Her work has been exhibited around the world, including museums and galleries in Germany, Greece, and Tokyo.[1] Her work was included in the 2004 Whitney Biennial and 2008 California Biennial.[2] She is on the graduate faculty at Otis College of Art and Design.[3]

Andrea Bowers | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1965 (age 54–55) |

| Alma mater | California Institute of the Arts, Bowling Green State University |

| Patron(s) | Otis College of Art and Design |

Early life and education

Andrea was born in Wilmington, Ohio, and grew up in "an apolitical Republican family."[4] She holds an MFA degree from California Institute of the Arts.[5] She also holds a BFA degree from Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio.[6]

Work

As a feminist and social activist, Bowers' work addresses contemporary political issues such as immigration, environmental activism, and rape, within the larger context of American history and protest movements.[7] Bowers regularly invites people who have a stake in the issues that concern her to enter the gallery spaces where she exhibits and directly engage with art world regulars. Examples of this include a series of activist events that took place at Susanne Vielmetter, and her decision to link the opening reception for her show "Mercy Mercy Me" (2009) at Andrew Kreps with an international day of action proposed by climate activist organization 350.org.[8] Bowers also continues to make a series of drawings based on photos of women taken at immigrant rights marches, feminist rallies, gay rights protests, and environmental activism in which the subjects are rendered in isolation on large sheets of otherwise blank paper. In Girlfriends (May Day March, Los Angeles, 2011) a feeling of isolation and vulnerability due to the subjects being out of context is particularly strong.[9]

Vieja Gloria

Vieja Gloria (2003) describes the clash between activist John Quigley and Los Angeles County authorities over the proposed removal of "Old Glory," a 400-year-old oak located in Valencia, California. Quigley later convinced Bowers to undergo training in tree climbing and occupation, which she documented in the video Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Training-Tree Sitting Forest Defense (2009). In 2011 she took part in a tree sit in Arcadia, which she also documented.

Sanctuary

Sanctuary (2007) is a film that comments on the ways marginalized people create spaces of refuge against overwhelming cultural and political forces. The silent film features Elvira Arellano, an undocumented immigrant who sought refuge in Chicago's Adalberto United Methodist Church. (Arellano and her eight-year-old son were eventually arrested and deported just three weeks after Bowers met with her).[10]

Circle

Circle (2009) is a video that depicts four generations of women from the Native Alaskan Gwich’in people speak about their ambivalent relationship with other, non-local, activists against oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Shots of a vast Arctic landscape suggest that petty differences may mean little in the context of the immensity that unites them. Bowers' focus on individual voices humanizes what might otherwise read as petty squabbling in the face of enormous challenges.

The United States v. Tim DeChristopher

In this video (2010) Bowers depicts environmental activist Tim DeChristopher speaking on camera about his sabotage of a 2008 government auction that was to make 150,000 acres of untouched Utah land available for oil and gas drilling. His account of deliberately fraudulent bidding is intercut with panoramic footage of the territory that was up for grabs; in each sequence, a tiny speck in the distance grows until the viewer can see that it is Bowers herself, carrying a slate on which she writes that location’s parcel number.

Transformer: Display

Transformer Display for Community Fundraising (2011) was created in collaboration with artist Olga Koumoundouros. Initially staged in Los Angeles, it consisted of a bricolage-based transient sculpture designed to raise money for and disseminate information about local activist organizations and neighborhood-based charities. A further incarnation at Art Basel Miami Beach (2011), titled Transformer: Display of Community Information And Activation, took the form of a cluster of activist kiosks and a replica of the semi-legendary Miami homeless camp Umoja Village, which burned down mysteriously in 2007 after the city’s efforts to remove it via legal means proved ineffective.[11]

#sweetjane

#sweetjane (2014) explores the Steubenville, Ohio, rape case and the social media-driven activism that brought the young men responsible to trial. At the Pitzer College Art Galleries was installed a 70-foot-long drawing of the text messages sent between the teenagers in the 48 hours after the assault on the young woman, who is known in the media and throughout the trial as Jane Doe.

The Pomona College Museum of Art housed a video installation comprising appropriated media footage and billboard-size photographs of disguised Anonymous protestors at the trial. Taken together, the installations critique the events and the young men, who were depicted sympathetically by the media, and the tolerance in the United States toward sexual assault.[12][13][14]

No Olvidado (Not Forgotten)

No Olvidado (Not Forgotten) is the title of one of Andrea Bowers’ largest and most well-known works. Covering three walls of her 2010 exhibition “The Political Landscape” at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, the piece consisted of a massive 10-foot-tall drawing that stretched for almost 96 feet. Against a smudgy graphite background, it portrayed the white ghost of a chain-link fence topped with coiled barbed wire, through which shone hundreds of names; each represented someone who died while trying to cross the Mexico/U.S. border.[10]

The list of names featured in the work was sourced from Border Angels, an organization that aims to protect those traveling through the Imperial Valley desert region, the mountains around San Diego County, and the border region itself.[15] Although the format echoed that of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the delicate materials and haunting imagery in Bowers’ piece evoked the shadowy lives of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Like many of her works, No Olvidado served as a deliberately transient monument to the marginalized and forgotten.[10]

Letters to an Army of Three

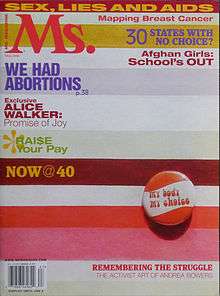

Bowers was alerted to a collection of letters from women seeking abortions prior to Roe v. Wade addressed to the Army of Three, a group of 3 activist women who advocated for the legalization of abortion in the United States in the decade preceding the Supreme Court decision.[16] The Army of Three had assembled a list of doctors who would provide abortions for women in need. Bowers employed what she describes as the “power of storytelling”[17] in the video installation, Letters to an Army of Three, in which actors read the letters aloud. The video was installed in her solo show at REDCAT. Bowers work has been credited with influencing political debates regarding reproductive rights. Though her work originated in response to the Bush Administration's position against abortion, it continued to be cited afterward.

Open Secret

Open Secret (2019) is a large-scale installation of draped printouts documenting the hundreds of men accused of sexual misconduct in the #MeToo era. The work became controversial when it was discovered that Bowers had used graphic photos of the bruised face and body of Helen Donahue, a sexual assault survivor, without Donahue's permission. Donahue was horrified to learn that images she had posted on Twitter in 2017 were being featured in an artwork that would be seen by tens of thousands of people and that reportedly had a price tag of $300,000.[18] The offending images were removed by Art Basel and Bowers issued a formal apology.[19][20]

Exhibitions

She has exhibited at venues including:

- the Vienna Secession

- REDCAT

- Santa Monica Museum of Art

- Whitney Museum of American Art

- Bard College

- Kunsthalle Basel

- the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles

- the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago

- the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati

- New Museum

- Frankfurter Kunstverein

- Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (Museum of Fine Arts)

- Hammer Museum

- Kunstmuseum Bonn[15]

- The Jewish Museum[21]

Awards and grants

2009

- Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award

2008

- United States Artists Broad Fellow

2003

- City of Los Angeles (C.O.L.A.) Fellowship Recipient for Visual Arts

1998

- Nominee: Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo per larte Prize

- WESTAF/NEA, Regional Fellowship for Visual Arts in Sculpture[22]

References

- "Andrea Bowers". Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- Pietsch, Stefan. "Andrea Bowers". This Long Century. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "Andrea Bowers". MFA Public Practice Faculty. Otis College of Art and Design. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Lawson, Thomas. "A Story about Civil Disobedience and Landscape: Interview with Andrea Bowers". East of Borneo. East of Borneo. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: Feminist Art Base: Andrea Bowers". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- Vielmetter, Susanna. "Susanna Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects". Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Los Angeles based artist Andrea Bowers opens first exhibition with Capitain Petzel". Artdaily.org. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- "A Story about Civil Disobedience and Landscape: Interview with Andrea Bowers". East of Borneo. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- "Andrea Bowers's "The New Woman's Survival Guide" | Art Agenda". www.art-agenda.com. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- "The Art and Activism of Andrea Bowers". Artpulse Magazine. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Rosenberg, Karen (December 2, 2011). "Art Basel Miami Beach – Review". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Maloney, Bad at Sports, Patricia. "Interview with Andrea Bowers | Art Practical". Art Practical. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Yoshimura, Courtney. "500 Words: Andrea Bowers". Artforum. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- "Project Series 48: Andrea Bowers: #sweetjane". Pomona College Museum of Art. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- Wilson, Michael (2013). How to Read Contemporary Art: Experiencing the art of the 21st Century. Abrams. p. 70.

- "10/08/14 Visual Thinker Lecture Series: Andrea Bowers". ibc.chapman.edu. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- Maloney, Bad at Sports, Patricia. "Interview with Andrea Bowers | Art Practical". Art Practical. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- Arnold, Amanda (June 12, 2019). "Artist Apologizes Over Tone-Deaf #MeToo Piece at Art Basel". The Cut.

- "Art Basel removes part of Andrea Bowers's work in Unlimited". theartnewspaper.com.

- Demopoulos, Alaina (June 12, 2019). "Andrea Bowers Apologizes for Using Image of #MeToo Survivor Without Consent in $300,000 Art Basel Work". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- "The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- LLC, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. "Biography of Andrea Bowers – Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects". www.vielmetter.com. Retrieved March 4, 2016.