Ancient Greek funerary vases

Ancient Greek funerary vases are decorative grave markers made in ancient Greece that were designed to resemble liquid-holding vessels. These decorated vases were placed on grave sites as a mark of elite status. There are many types of funerary vases, such as amphorae, kraters, oinochoe, and kylix cups, among others. One famous example is the Dipylon amphora. Every-day vases were often not painted, but wealthy Greeks could afford luxuriously painted ones. Funerary vases on male graves might have themes of military prowess, or athletics. However, allusions to death in Greek tragedies was a popular motif. Famous centers of vase styles include Corinth, Lakonia, Ionia, South Italy, and Athens.[1]

Uses

One major type of funerary vase was the krater, a mixing bowl for wine and water used by elite Greek males at symposiums. Symposiums were an eastern influence[2] in which the aristocracy would lie down and drink; many Greek painters referenced this lifestyle in their art. The krater was so symbolic of elite status that large, richly decorated kraters would be placed upon grave sites. Although in the shape of drinking vessels, some funerary kraters were made just to be a grave marker, as indicated by a hole in the bottom of the vessel. This hole would allow libations to drain through.[3]

The display of highly decorated funeral vase markers, along with costly grave goods, and elaborate processions, helped to display the status of wealthy families. This act is called conspicuous consumption, and would let the whole community know who held power in the region.[4]

Types

The amphora was a tall, slender pot that often held oil, wine, milk, or grain.[1] These could be as tall as an adult, and were both practical for transporting goods, and artistic in their funerary usage. Amphorae filled with oil were awarded to victorious athletes during Panathenaic games, with the winner painted on it.[2] These might be placed on the grave of the athlete.

The Lekythos was another style of funerary vase that usually held ritual oil. It had a slender body with a single handle. One famous artist of lekythoi was the Achilles painter. Funeral lekythoi were often painted in the white ground technique.

The kylix (kylikes, plural), popular at symposiums, was a stout drinking cup with a very wide bowl. A well known potter of kylikes was Exekias. After being formed separately on the potter's wheel, the bowl and stem would be left to dry. The cup would then be placed upside down to attach the handles. The handles would dry in this upside down position, giving the handles a unique upturned curve when the kylix was upright.[5]

An oinochoe was a stout wine jug with a distinct pouring lip, and a large handle. The name comes from oinos (wine), and cheo (to pour).[6] Some of these have relief sculpture under the bowl. There are two other variations of oinochoe that differ in size and style, called olpe and chous.

The hydria was a water-containing vessel with three handles; two for carrying, and another for pouring. These could also be made out of bronze. A well preserved example is the Regina Vasorum from Southern Italy.[7] The Regina Vasorum has black lacquer with gilding. Demeter, Athena, Artemis, Aphrodite, and Dionysus can all be seen on this hydria.[7]

Iconography

2.jpg)

Geometric patterns adorn many vases between 900-700 B.C.[8] These patterns include meanders, right-angles, and swastikas. Most vases from this period were found in cemeteries, thus becoming our primary source of knowledge during the Geometric period.[9] In the 600s B.C., Athens moved away from abstract geometric patterns, and toward more natural art, influenced by the Near East.[10]

Images from vases can provide information about religion, beliefs, and how people lived, including burial rites. Burial customs included washing and dressing the body in ointments before wrapping the body in a shroud and outer cloth. The body would then be laid upon a bier, or funeral bed, which gives form to the Greeks' association between sleep and death.[11]

Thanatos, the god of gentle death, can be seen on Greek funerary vases taking away the body of the deceased to the underworld. The act of laying out the body for mourners to see, called prothesis, is painted on the Dipylon amphora. The next step was the ekphora; the moving of the body to a cemetery in a procession. If cremation was practiced, the ashes of the deceased would be placed inside the funeral vase, and buried.

.jpg)

Social connections

Kylikes, used at symposiums, would often be painted with large eyes on them. When drinking from these eye-cups, they would act as a mask, like actors would wear in a play. These eyes would stare at the other guests, with the handles resembling ears. The Greek word for handle is "ous", meaning ear.[2] The altered state of mind that comes from drinking alcohol is analogous to putting on the mask of someone else. This connection between wine, masks, and stories told at symposiums were all embodied in the god Dionysus, the god of wine and theater.[2]

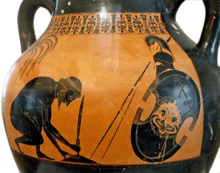

Tragedy on vases

Greek tragedies were a popular motif on funeral vases which often contained the death of someone close to the main character within the play. An example of this is the suicide of Ajax vase. Greeks would see these pictures of Greek tragedies on vases, which would remind them of the suffering that heroes of old had to endure. They believed that If great heroes were able to survive life's sufferings, then so could they.[12] In this way, they could view tragedy as something comforting, thus giving people the strength to persevere.[12] Through visual depictions of tragedies, the Greeks could relate to the deceased. Pots that depict funerary scenes were usually designed for tombs. However, vases with comical motifs have also been found in graves.

See also

References

- "A Story on a Vase (Education at the Getty)". www.getty.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- Neer, Richard T (2012). Greek art and archaeology: a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500288771.

- "CU Classics | Greek Vase Exhibit | Essays | Burial Customs". www.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- Pedley, John Griffiths (2012). Greek art and archaeology. New York (N.Y.): Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780205001330.

- Noble, Joseph Veach; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y) (1965). The techniques of painted Attic pottery. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications.

- "Perseus Encyclopedia, Oak, Oinochoe". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "Art works". www.hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- Biers, William R (1996). The archaeology of Greece: an introduction. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801431735.

- Rasmussen, Tom; Spivey, Nigel Jonathan (2009). Looking at Greek vases. Cambridge [England]; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521376792.

- "Attributed to the New York Nessos Painter | Terracotta neck-amphora (storage jar) | Greek, Attic | Proto-Attic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "CU Classics | Greek Vase Exhibit | Essays | Burial Customs". www.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- Taplin, Oliver (2007). Pots & plays: interactions between tragedy and Greek vase-painting of the fourth century B.C. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Further reading

- Coldstream, J. N. Geometric Greece. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1977.

- Garland, Robert. The Greek Way of Death. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Kästner, Ursula, et al. Dangerous Perfection : Ancient Funerary Vases from Southern Italy / Ursula KäStner and David Saunders, Editors; with Contributions by Ludmila Akimova, Marie Dufková, Andrea Milanese, Elena Minina, Sonja Radujkovic, Dunja RüTt, Priska Schilling-Colden, Marie Svoboda, Mark Weir, Bernd Zimmermann. 2016.

- Mertens, Joan R. How to Read Greek Vases / Joan R. Mertens. New York : New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Distributed by Yale University Press, 2010.

- Neer, Richard T. 2012. Greek art and archaeology: a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE.

- Pedley, John Griffiths. Greek Art and Archaeology. 2d ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

- Schweitzer, Bernhard. Greek Geometric Art. New York: Phaidon, 1971.

- Smith, H. R. W., and J. K. Anderson. Funerary Symbolism in Apulian Vase-painting / by H. R. W. Smith; Edited by J. K. Anderson. University of California Publications. Classical Studies; v. 12. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.