Anchor Line (riverboat company)

The Anchor Line was a steamboat company that operated a fleet of boats on the Mississippi River between St. Louis, Missouri, and New Orleans, Louisiana, between 1859 and 1898, when it went out of business. It was one of the most well-known, if not successful, pools of steamboats formed on the lower Mississippi River in the decades following the American Civil War.

History

Early years, 1859-1879

The company was founded in 1859 as the Memphis and St. Louis Packet Line, principally providing service to these two cities and points in between. Two years later, the American Civil War broke out. Whereas many steamboat owners were forced to cease operations at the outbreak of hostilities, the Memphis and St. Louis Packet Line managed to remain in business by operating on the parts of the Mississippi River occupied by the Union forces. By the spring of 1862, this included all parts of the river as far south as Memphis. One year later, all ports on the river except for Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana, were under Federal control. On 4 July 1863, Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant forced the Confederate garrison commanded by John C. Pemberton to surrender Vicksburg, and the next day, Port Hudson surrendered, opening the river to commercial steamboat traffic.

In 1874, the company adopted the giant anchor as its symbol (and presumably changed its name at that date). In any case, by the mid-1870s it was known as the "Anchor Line." The anchor was prominently hung between the two tall smokestacks on each of its boats. It was also included as a logo on the furnishings of many of its boats, including the chairs manufactured for the boats' cabins.

The golden era, 1880-1894

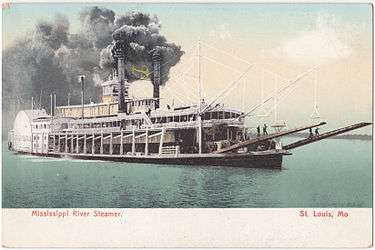

By the early 1880s, the company had acquired sufficient capital to justify the building of several new steamboats. Almost all of these boats were built by the Howard Shipbuilding Company of Jeffersonville, Indiana. The Anchor Line spared no expense on the building of these boats, which became veritable floating palaces of the late American Victorian era. Between 1880 and 1887, the Anchor Line built no fewer than ten of these extravagant steamboats, which averaged each about 275 feet (83.33 m) in length from bow to stern and about 45 feet (13.64 m) in width. In contrast to the common practice of naming steamboats after people or after some pleasant-sounding idea, feeling, or animal, the Anchor Line chose to name these craft after cities along its route. The first of these to be built was the Belle Memphis, which, after it steamed out of St. Louis in early 1881 and first docked at Memphis, was presented by the city with a gift of a set of flags.

Most of these boats survived the common disasters that were known to plague Mississippi River steamboats at the time, such as fire, snags (large sticks or branches in the river bed that would often tear holes in boats' hulls), ice, grounding on sandbars, and so forth to remain in service with the Anchor Line from the day they were built until the company went out of business in 1898. One of them, the City of Providence, built for the Anchor Line in 1880, was sold when the Anchor Line was liquidated and was then operated by various excursion companies until it was finally destroyed by ice in January 1910, some twenty-nine years after it was first put into service.

Decline and collapse, 1894-1898

Problems of the River itself

The Mississippi River proved throughout the nineteenth century to be a volatile and sometimes hazardous or unnavigable road for boat traffic. Despite the best efforts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, high water would swallow landings, making many smaller stops unavailable for steamboats. Likewise, low water would strand these towns far from any suitable site for boats to land (or, conversely, strand steamboats at landings in water with no outlet to a navigable channel), and increase the possibility that hazards such as snags would pierce steamboats' hulls. Floods, such as the great Flood of 1892 (during which all of Concordia Parish, Louisiana, was said to be underwater), could destroy crops that would comprise a sizable portion of the cargo transported by steamboats such as those of the Anchor Line, thus also cutting off a sizable portion of the steamboats' business. The early 1890s, particularly 1892 and 1894, seem to have been years where conditions on the river significantly affected the Anchor Line's business.

Competition from railroads

Added to the problems inherent with river traffic was the increasingly expanding railroad network in the United States, which soon came into direct competition with steamboats for business, both from passengers and from cargo. Rail travel was not subject to the dictates of the river's course (tracks could be laid on ground virtually anywhere in the Mississippi valley), servicing directly more towns than any steamboat could. Trains were generally safer than steamboats, as well, being not prone to snags, sandbars, ice, or other problems particular to river travel. Finally, trains were faster, as they generally traveled much quicker than the 15 mph (24.3 km/h) averaged by late-nineteenth-century Anchor Line boats.

The 1896 tornado

Historians say that the Anchor Line was ultimately doomed by the 1896 St. Louis–East St. Louis tornado that struck on May 27. The tornado touched down in the core of St. Louis and swept eastward across the river into East St. Louis, Illinois. The resulting death toll was a confirmed 255 people, though estimates put the number at close to 400. This is in part because the Anchor Line's floating palaces (as well as other steamboats) stationed at the St. Louis landing lay directly in the tornado's path. The Anchor Line's boats the Arkansas City and the City of Cairo were completely destroyed, and the City of Monroe was badly damaged.

Later that year the company launched another boat, the Bluff City. In 1897, the Anchor Line repaired, extended, and installed electric lights on the City of Monroe, renaming it the Hill City. It issued a 22-page brochure, entitled A Romantic Trip to the Sunny South, in an attempt to lure passengers. Nonetheless, that same year the Bluff City was destroyed by fire, the Belle Memphis was irreparably damaged by a snag, and the City of Hickman, sank.

The disasters ultimately proved too costly for the Anchor Line to weather, and in 1898 it sold off its remaining boats and ceased operations.

Route

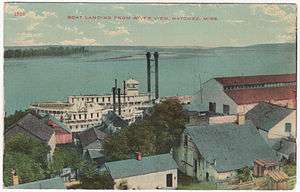

The Anchor Line served most cities between St. Louis and New Orleans, as well as many smaller landings on occasion or by special request of passengers. Not all Anchor Line steamboats traveled this entire route regularly; for example, between 1888 and 1896, the Arkansas City worked a route between St. Louis and Natchez.

Main landings probably included:

- Cairo, Illinois

- New Madrid, Missouri

- Hickman, Kentucky

- Memphis

- Helena, Arkansas

- Greenville, Mississippi

- Vicksburg

- Natchez, Mississippi (and Vidalia, Louisiana, across the river)

- Bayou Sara, Louisiana

- Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Donaldsonville, Louisiana

- New Orleans

Boats

Beginning in 1880, all newly built Anchor Line Boats were side-wheelers, meaning they each had two large paddlewheels located on the starboard and port side of the boat, located about two-thirds of the way back from the prow. The lone exception was the Bluff City.

| Boat | Year built | |

| Belle Memphis (I) | 1866 | Side-wheeler. Measured 260 ft (79 m) long x 40 ft (12 m) wide x 7 ft (2.1 m) depth (hull). Usually operated between St. Louis and Memphis. Dismantled in 1880, when its engines were probably used in the construction of the second Belle Memphis (see below). |

| James Howard | 1870 | Side-wheel packet built by Howard. A large boat, measuring 320 ft (98 m) long x 53 ft (16 m) wide x 10 ft (3.0 m) depth. The Howard was built for Capt. Rush Pegram and others for the St. Louis-New Orleans trade at a cost of $180,000. Stood for public inspection in Cincinnati on 21 January 1871, where an estimated 45,000 visitors boarded the boat. Bought from Pegram by the Anchor Line in 1878. The boat could carry 3,200 tons, as evidenced by the cargo she transported on one trip in January 1881. Burned at St. Louis on 13 March 1881, having just arrived from New Orleans with a cargo of sugar. All passengers and crew escaped safely. |

| City of Vicksburg (I) | 1870 | Side-wheel packet built by Howard. 265 x 42 x 8. Commanded by Capt. Robert Riley. Sank on a snag at Ashport, Tennessee, 11 August 1880, while carrying a large cargo. |

| Belle Memphis (II) | 1880 | The second Memphis had dimensions of 267 x 42 x 7.5. her engines were not new, and probably used from the previous incarnation (see above). Ran her maiden voyage from St. Louis to Memphis in 1881, where she was presented with a piano and set of flags. Her first captain was Ike McKee, who, at age 64, was the oldest in the Anchor Line. Circa 1895, her pilot was Horace Bixby (1826 – 1912), who is featured in Mark Twain's writings. Damaged beyond repair by a snag in early September 1897 at Crane's Island, just south of Chester, Illinois. |

| City of Providence | 1880 | The longest-lived Anchor Line boat. Destroyed by ice in 1910, twelve years after the Anchor Line sold it to an excursion company. |

| City of Vicksburg (II) | 1881 | Typical size for Anchor Line boats. Sold in 1894 to an excursion company, which continued to operate it under the same name. Damaged in the 1896 St. Louis tornado. Sold again and rebuilt under the name Chalmette. Sank in 1904. |

| City of Cairo | 1881 | Worked for the Anchor Line for 15 years, until destroyed by the 1896 tornado. |

| City of Baton Rouge | 1881 | Dimensions: 294 ft (90 m) x 49 ft x 9 ft 5 in (2.87 m) Oddly, on her delivery from Howard, she stuck on rocks at the Falls of Louisville, Kentucky, where she remained for three weeks. Operated on the route from St. Louis to New Orleans, and was commanded by Horace Bixby for much of her career. Sank at Hermitage, Louisiana, at 3 PM on 12 December 1890, with the loss of two deck passengers. |

| City of New Orleans | 1881 | Dimensions: 290 ft (88 m) x 48 ft x 8.5 ft (2.6 m) Between 1885 and 1891 her captain was A.J. Carter with Archie Woods, clerk. By 1896, A.S. Lightner had become captain, with J.W. Langlois as clerk. Brought under her own steam in May 1898 to Harmar, Ohio, where she was dismantled at the Knox Boat Yard, and much of her equipment used for the City of Pittsburg, which operated 1898-1902 before being lost to fire. |

| Arkansas City | 1882 | Operated by the Anchor Line continuously for fourteen years. First came as far south as Natchez in 1888, and after that principally worked a route between there and St. Louis. Demolished in the 1896 St. Louis tornado and never repaired. |

| Will S. Hayes | 1882 | Sold to the Anchor Line sometime after this date, though one source (the Gandys) report that it was actually built for the Anchor Line at that time. |

| City of St. Louis | 1883 | Measured 300 feet (91 m) long x 49 feet (15 m) wide x 8.6 feet (2.6 m) depth (hull). In 1894 she was commanded by Captain James O'Neal, with pilots Joe Bryan and Charlie O'Neal. In March 1898 she was bought at the U.S. marshal sale at St. Louis by Captain W.H. Thorgewan for $19,050 (about $422,0064 in 2005). Briefly owned afterwards by the Columbia Excursion Company, which sold the boat in July 1899 to James M. Grasty. By 1901 she was running harbor excursions in New Orleans, and U.S. President William McKinley rode on the boat in May. Grasty sold the boat in 1903 to the Greater New York Home Oil Company; however, a U.S. marshal took control of the boat and sold her to T. Marshall Miller, an attorney, for $3,125 (2005 $66,573). Laid up at Carondelet, Missouri, she burned there 29 October 1903. The original roof bell was sold by the Anchor Line to Captain J. Frank Ellison, and it was later installed on a boat known as the Queen City. |

| City of Bayou Sara | 1884 | Said to have been a larger-than-average Anchor Line boat, measuring 300 ft (91 m) x 48 ft x 9 ft 10 in (3.00 m) Commanded by Captain Isaac Baker, her other officers included John E. Massengale, purser; Collin Baker, 2nd clerk; George Murray and Theodore Hall, pilots; and Tobe Royal, mate. Burned on 5 December 1885 while loading corn at New Madrid, Missouri. Eight people died in the fire. |

| City of Natchez | 1885 | Had dimensions of 300 ft (91 m) x 48 ft x 10 ft (3.0 m) Horace Bixby was her captain, with H.E. Corbyn as her clerk. Said by Frederick Way (below) to have been the "brag boat of the Anchor Line." Lost to a fire on 28 December 1886 at Cairo, Illinois, that broke out on the neighboring towboat R.S. Hayes. |

| City of Monroe | 1887 | Named for the Monroe, Louisiana on the Ouachita River, which was served only indirectly by the Anchor Line. Upon first arrival in Natchez in 1888, presented with piano and flags by a delegation from Monroe. Said to have been a popular boat. Damaged in the 1896 tornado in St. Louis. Rebuilt, extended by being cut down the middle, outfitted with electric lights, and renamed Hill City. Sold by the Anchor Line in 1898 to an excursion company. Sank in 1900, but raised later that year. Renamed again as the Corwin H. Spencer and took on passengers at the St. Louis World's Fair, though destroyed by fire near Jefferson Barracks on 12 October 1905. |

| City of Hickman | 1894? | Sank in 1896. |

| Bluff City | 1896 | Only stern-wheeler built by the Anchor Line. Burned a year after its construction. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anchor Line (riverboat company). |

References

- Gandy, Joan W. and Thomas H. The Mississippi Steamboat Era In Historic Photographs: Natchez to New Orleans, 1870-1920. New York: Dover Publications, 1987.

- Way, Frederick Jr. Way's Packet Directory, 1848-1994: Passenger Steamboats of the Mississippi River System Since the Advent of Photography in Mid-Continent America, 2nd ed. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1994.