An Wasserflüssen Babylon (Reincken)

An Wasserflüssen Babylon is a chorale fantasia for organ by Johann Adam Reincken, based on "An Wasserflüssen Babylon", a 16th-century Lutheran hymn by Wolfgang Dachstein. Reincken likely composed the fantasia in 1663, partly as a tribute to Heinrich Scheidemann, his tutor and predecessor as organist at St. Catherine's Church, Hamburg.[3] With its 327 bars, it is the most extended repertoire piece of this kind.[4][5] Reincken's setting is a significant representative of the north German style of organ music.[5][6]

History

The text of Wolfgang Dachstein's "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" (By the Rivers of Babylon) is a paraphrase of Psalm 137 (Super flumina Babylonis), Jews lamenting their Babylonian captivity. Its hymn tune is in bar form:[10][11][12]

The hymn was published in 1525, and was adopted in several major German hymnals by 1740.[10]

Heinrich Scheidemann can be considered the inventor of the chorale fantasia for organ, and, based on over fifteen attributable compositions, the most prolific contributor to this genre.[13] It was an expansion of the Fantasia genre as developed by Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck.[5] Around the mid-1650s Reincken was, probably in about the same period as Dieterich Buxtehude, Scheidemann's pupil for a few years, after which he returned to the Netherlands.[14] Called back by his former teacher in 1659, he became his assistant as organist at the St. Catherine's Church in Hamburg.[14] Around 1660 the stylus fantasticus was the dominant style among the organists in Hamburg, of which the chorale fantasias by both Reincken and Buxtehude bear the mark.[5]

In 1663 Scheidemann died and Reincken succeeded him as organist of the St. Catherine's Church.[3][14] Allein zu dir, a late chorale fantasia by Scheidemann, shares many characteristics with Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon, so it is assumed that Reincken composed his setting around the same time, as masterpiece to conclude his schooling,[5] or, most likely, when he assumed his position as successor of Scheidemann at St. Catherine's.[3] Reincken's chorale setting appears not to have been intended for liturgical use, neither as a prelude to a sung chorale, nor for alternatim performance, but rather as a model for improvisation, showing several techniques.[15]

Music

In his An Wasserflüssen Babylon, Reincken covers all of the techniques of the chorale fantasia: cantus firmus, fugue, echo, figurative writing, and embellished chorale.[4] The composition presents itself as a compendium of the north German style of organ music.[5][7] The verses of Dachstein's chorale are in ten lines.[4] Lines three and four are sung to the same melody as the first two lines, which is the Stollen of the chorale tune, thus lines one and two can be indicated as first Stollen, and the next two lines as repeat of the Stollen.[5] Following Sweelinck's scheme for a fantasia, Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon has three sections, "Exordium" (exposition), "Medium" (middle section) and "Finis" (finale):[5]

- Exordium

- Medium

- bars 108–235, lines 5–8 of the hymn.[5]

- Finis

- bars 236–327, lines 9–10 of the hymn.[5]

Bars 1–107

In the "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" hymn, the Stollen is the tune for two lines of text, here represented by two bars:[5][16]

First Stollen

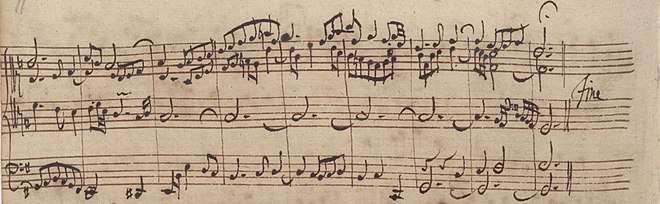

The first two lines of the hymn text, or the first Stollen, are the subject of the first 81 bars of Reincken's chorale fantasia.[5] The melody of the first line of the hymn is recognisable as a cantus firmus in the tenor voice in the first six bars of the composition:[17][18]

The first Stollen section develops as a monody (played by the right hand) over a fugal setting, which is a technique typical of Scheidemann's chorale preludes. Thus, according to Pieter Dirksen, this first Stollen episode can be seen as Reincken's tribute to Scheidemann.[3][5]

The two lines are each treated with a dense counterpoint, which is similar for both lines. Over-all the figuration recedes in favour of a motet-like polyphony.[5]

Repeat of the Stollen

The repeat of the Stollen, lines three and four of the hymn text, follows in bars 82 to 107. The repeat of the Stollen is shorter than the first Stollen, and introduces an element of virtuosity. In the third line the left hand plays, with imaginative embellishments in the tenor voice, up to the highest notes on the keyboard, while the fourth line is characterised by ornamentation of the treble voice.[4][5]

Bars 108–235

Lines five to eight of the hymn tune have this melody, each line represented by a bar:[12]

With its 128 bars this is the most extended section of the chorale fantasia, and treats, consecutively, lines five to eight of the chorale. The section has a symmetrical build: the outer episodes (lines five and eight) both elaborate a similar canzona-like theme, and the central episodes (lines six and seven) both have dotted rhythms and use the echo technique.[5]

Bars 236–327

Although the last section of the chorale fantasia elaborates only the remaining two lines of the "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" hymn, it is nonetheless in four episodes, like the preceding section.[5]

Ninth line

The penultimate line of the chorale tune,[12]

is elaborated twice in bars 236–290:[5]

- First as a stylistically archaic canon, ending with an augmented cantus firmus in the pedal.[5] The double diminution in this passage is similar to a passage in Scheidemann's Allein zu dir, bars 87ff.[19]

- Next as a dramatic interaction that seems inspired by vocal forms such as the Geistliches Konzert.[5]

Tenth line

The last line of the chorale tune,[12]

is, from bar 291, first treated in a dialogue-like echo setting, followed by an extended virtuoso coda which also uses the echo technique.[5] These final passages of the chorale fantasia, starting with fast melody lines in both hands imitating each other almost as a canon, are very close to how Scheidemann's Allein zu dir ends.[3]

shows an unusual gesture: the melody line descends in a scale to the end note.[20]

Reception

According to an anecdote in Johann Gottfried Walther's Musicalisches Lexikon (1732), Reincken sent a copy of his An Wasserflüssen Babylon, as a portrait of himself, to a great musician in Amsterdam who had commented on his recklessness to succeed such a famous man as Scheidemann. This copy is lost: a copy of the work surviving in Amsterdam was sent there in the 19th century, based on a Berlin manuscript.[5][22][23][24]

As reported in his obituary, published in 1754, Johann Sebastian Bach knew Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon chorale setting.[11][25][26] Two and a half centuries later it became clear that Bach had known the piece since he was a teenager.[1][27] When he was studying in northern Germany in the early 18th century, Bach visited Hamburg several times to hear Reincken play.[28] The earliest known versions of Bach's organ setting of Dachstein's hymn, BWV 653b and 653a, originated in his Weimar period (1708–1717).[29] In the early 1720s Bach improvised for nearly half an hour on "An Wasserflüssen Babylon" at the organ of St. Catherine's Church in Hamburg, a performance which was attended by the ageing Reincken.[11][25][26][27][30] When the concert was concluded, Reincken commended Bach for this improvisation: "I thought this art was dead, but I see that it survives in you."[11][25][26][27][30] In the second half of the 1740s, Bach reworked his An Wasserflüssen Babylon chorale prelude to the BWV 653 version included in the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes, adding a seven-bar coda:[20][31]

This coda ends with a descending scale reminiscent of the one that ends Reincken's setting (see above): Russell Stinson interprets this as a musical homage to Reincken.[20] He writes, "It is hard not to believe that this correspondence represents an act of homage."[20] Despite being composed in Leipzig within the traditions of Thuringia, however, Bach's contemplative "mesmerising" mood is far removed from his earlier improvisatory compositions in Hamburg and Reincken's chorale fantasia: the later chorale prelude is understated, with its cantus firmus subtly embellished.[32][33]

In the first part of his Bach biography, published in 1873, Philipp Spitta recognises that Reincken's chorale fantasia received some extra lustre through the anecdote involving Bach, adding that it is nonetheless a work worth to be considered in its own right.[27][34] Writing in the next decade, August Gottfried Ritter is less favourable about the composition, describing its artificiality as disconnected from liturgical praxis.[27]

Score editions

In 1974 Breitkopf & Härtel published Reincken's organ works, including An Wasserflüssen Babylon, edited by Klaus Beckmann.[18][35] Two extant copies of Reincken's composition were known at the time of publication, both of them deriving from the lost Berlin manuscript.[36] Beckmann's edition of the work for Schott was published in 2004.[37] Pieter Dirksen provided a new edition for Breitkopf: in the preface of this 2005 publication he describes the chorale fantasia as being transmitted via a single source.[17][38]

Around 2006 Michael Maul and Peter Wollny recovered the Weimarer Orgeltabulatur, containing a previously unknown organ tablature version of Reincken's An Wasserflüssen Babylon.[39] This copy of the chorale fantasia had originated in the late 17th century in the circles of Georg Böhm: an endnote on the manuscript, in Johann Sebastian Bach's hand, dates it to 1700.[1] After having published a facsimile of this manuscript in 2007, Maul and Wollny published an edited score of the same in 2008.[2][40]

Recordings

| Rec. | Organ | Organist | Album | Dur. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Schnitger, Noordbroek | Leonhardt | The Historic Organ: Holland. Telefunken, Das Alte Werk, 1968. SAWT 9521-B (LP) | 17:22 |

| 1970 | Garrels, Purmerend | Jongepier | Historische opnamen van het Garrels-orgel Purmerend. VLS, 2000. SRGP01 (CD) | 19:30 |

| 1990 | Schnitger, Groningen | Vogel | Arp Schnitger Opera Omnia, Vol. 1. Organa, 1991. ORA 3301 (CD) | 19:13 |

| 1994 | Hus/Schnitger, Stade | Böcker | Denkmäler Barocker Orgelbaukunst: Die Huß/Schnitger-Orgel in SS. Cosmae et Damiani zu Stade. Ambitus, 1995. AMB 97 800 (CD) | 17:16 |

| 1999 | Schnitger, Hamburg | Foccroulle | J. A. Reinken, N. Bruhns: Sämtliche Orgelwerke. Ricercar, 2002. RIC 204 (CD) | 16:50 |

| 2000 | Schnitger, Groningen | Vogel | Historische Orgels, Vol. 1: Schnitger-Orgel der Aa-kerk Groningen. Organeum, 2003. OC-39902 (CD) | 16:30 |

| 2006 | Schnitger, Hamburg | Zehnder | J. S. Bachs früheste Notenhandschriften. Carus, 2006. 83.197 (CD) | 19:16 |

| 2006 | Hagelstein, Gartow | Flamme | J. A. Reincken • Kneller • Geist: Complete Organ Works. cpo, 2007. 777 246-2 (SACD/CD hybrid) | 15:40 |

| 2008 | Schonat, Amsterdam | Winsemius | North German Baroque, Vol. II: Bernard Winsemius. Toccata, 2016. TRR 99017 (CD) | 18:07 |

| 2011 | Verschueren, Dordrecht | Ardesch | Inventio 1. MPD-classic, 2012. 20071010 (CD) | 21:24 |

| 2012 | Zanin, Padua | Stella | Reincken: Complete harpsichord and organ music. Brilliant, 2014. 94606 (CD) | 18:01 |

| 2013 | Stellwagen, Stralsund | Rost | Die Norddeutsche Orgelkunst, Vol. 3: Hamburg. MDG, 2013. 320 1816-2 (CD) | 16:40 |

| 2013 | Flentrop, Hamburg | van Dijk | Regina Renata: Die Orgel in St. Katharinen Hamburg. Es-Dur, 2014. ES 2050 (CD) | 19:11 |

| 2014 | Flentrop, Hamburg | de Vries | Sietze de Vries: Katharinenkirche Hamburg. Fugue State, 2014. JSBH011214 (CD)[9] | 20:51 |

References

- Beißwenger 2017, pp. 248–249.

- Bach 2007.

- Dirksen 2017, p. 116.

- Shannon 2012, p. 207.

- Dirksen 2005, p. 4.

- Wolff 2000, p. 64.

- Collins 2016, p. 119.

- Musical Company, Johannes Voorhout, 1674 at the Hamburg Museum website.

- Hofwegen 2014.

- Leahy 2011, p. 37.

- Stinson 2001, p. 78.

- Terry 1921.

- Dirksen 2005, p. 3–4.

- Dirksen 2005, p. 3.

- Belotti 2011.

- Stinson 2012, Chapter 2: "Bach and the Varied Stollen", pp. 28–39.

- Reincken 2005.

- Reincken 1974.

- Dirksen 2017, pp. 112, 116.

- Stinson 2001, pp. 79–80.

- Reincken 1974, p. 21.

- Belotti 2011, pp. 103–104.

- Beckmann 1974, p. 45.

- Walther 1732.

- Shute 2016, pp. 39–40.

- Agricola & Bach 1754, p. 165.

- Belotti 2011, p. 104.

- Forkel & Terry 1920, pp. 12–13.

- Works 00745 and 00744 at Bach Digital website.

- Forkel & Terry 1920, pp. 20–21.

- D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 271, Fascicle 2 at Bach Digital website (Mus.ms. Bach P 271 at Berlin State Library website), RISM No. 467300876, p. 68

- Geck, Martin (2006), Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work, translated by John Hargraves, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 507–509, ISBN 0151006482

- Williams, Peter (2003), The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 348–349, ISBN 0-521-89115-9

- Spitta 1899, p. 198.

- Collins 2016, footnote 64 p. 207.

- Beckmann 1974, p. 45–46.

- Reincken 2004.

- Dirksen 2005, p. 6.

- Stinson 2011, pp. 16, 186.

- Reincken 2008.

Sources

- Agricola, Johann Friedrich; Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1754). "Chapter VI, section C (known as Bach's Nekrolog)". In Mizler, Lorenz Christoph (ed.). Musikalische Bibliothek (in German). IV/1. Leipzig: Mizler. pp. 158–176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bach, Johann Sebastian (2007). Maul, Michael; Wollny, Peter (eds.). Weimarer Orgeltabulatur: Die frühesten Notenhandschriften Johann Sebastian Bachs sowie Abschriften seines Schülers Johann Martin Schubart − Mit Werken von Dietrich Buxtehude, Johann Adam Reinken und Johann Pachelbel (Facsimile). Documenta musicologica II. 39. ISBN 9783761819579.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckmann, Klaus (1974). "Revisionsbericht". Joh. Adam Reincken: Sämtliche Orgelwerke. Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 45–48.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beißwenger, Kirsten (2017). "Other Composers". In Leaver, Robin A. (ed.). The Routledge Research Companion to Johann Sebastian Bach. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781409417903.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Belotti, Michael (2011). Miklavčič, Dalibor (ed.). "Die norddeutsche Choralbearbeitung - rein funktionale Musik?". Muzikološki zbornik / Musicological Annual (in German). Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana, Philosophical Faculty. 47 (2): 103–113. ISSN 0580-373X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Paul (2016). The Stylus Phantasticus and Free Keyboard Music of the North German Baroque. Routledge. ISBN 9780754634164.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dirksen, Pieter (2005). "Vorwort" (PDF). Johann Adam Reincken: Sämtliche Orgelwerke / Complete Organ Works. Breitkopf Urtext (in German). Breitkopf. pp. 3–6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dirksen, Pieter (2017). Heinrich Scheidemann's Keyboard Music: Transmission, Style and Chronology. Routledge. ISBN 9781351563987.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forkel, Johann Nikolaus; Terry, Charles Sanford (1920). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Life, Art and Work – translated from the German, with notes and appendices. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hofwegen, Chiel-Jan van (2014). "Sietze de Vries − Katharinenkirche Hamburg". orgelnieuws.nl (in Dutch).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leahy, Anne (2011). "2. An Wasserflüssen Babylon". J. S. Bach's "Leipzig" Chorale Preludes: Music, Text, Theology. Contextual Bach Studies. 3. Scarecrow Press. pp. 37–58. ISBN 9780810881815.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reincken, Johann Adam (1974). "Nr. 1 An Wasserflüssen Babylon". In Beckmann, Klaus (ed.). Sämtliche Orgelwerke. Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 4–21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reincken, Johann Adam (2004). "An Wasserflüssen Babylon (Chorale fantasia)". In Beckmann, Klaus (ed.). Complete Organ Works. Masters of the North German School for Organ. 11. Schott. ISBN 978-3-7957-9773-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reincken, Johann Adam (2005). "1. An Wasserflüssen Babylon". In Dirksen, Pieter (ed.). Complete Organ Works. Breitkopf Urtext. Breitkopf.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reincken, Johann Adam (2008). "I. An Wasserflüssen Babylon". In Maul, Michael; Wollny, Peter (eds.). Weimarer Orgeltabulatur. Bärenreiter. ISMN 9790006534685.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shannon, John R. (2012). The Evolution of Organ Music in the 17th Century: A Study of European Styles. McFarland. ISBN 9780786488667.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shute, Benjamin (2016). Sei Solo: Symbolum?. Pickwick Publications. ISBN 9781498239417.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spitta, Philipp (1899). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750. I. Translated by Clara Bell and J. A. Fuller Maitland. Novello & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stinson, Russell (2001). "An Wasserflüssen Babylon (By the Waters of Babylon), BWV 653". J. S. Bach's Great Eighteen Organ Chorales. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–80. ISBN 0195116666.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stinson, Russell (2012). J. S. Bach at His Royal Instrument: Essays on His Organ Works. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199917235.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1921). "An Wasserflüssen Babylon". The Hymns and Hymn Melodies of the Organ Works. Bach's Chorals. III. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 101–105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walther, Johann Gottfried (1732). "Scheidemann (Heinrich)". Musicalisches Lexikon (in German). Leipzig: W. Deer. pp. 547–548.

Scheidemann ... ist ... so wohl wegen seiner Composition als seines Spielens dergestalt berühmt gewesen, daß ein grosser Musicus zu Amsterdam, als er gehöret, daß Adam Reincke an des Scheidemanns Stelle gekommen, gesprochen: „es müsse dieser ein verwegener Mensch seyn, weil er sich unterstanden, in eines so sehr berühmten Mannes Stelle zu treten, und wäre er wohl so curieux, denselben zu sehen.“ Reincke hat ihm hierauf den aufs Clavier gesetzten Kirchen-Gesang: An Wasser-Flüssen Babylon, mit folgender Beyschrifft zugesandt: Hieraus könne er des verwegenen Menschen Portrait ersehen. Der Amsterdammische Musicus ist hierauf selbst nach Hamburg gekommen, hat Reincken auf der Orgel gehöret, nachher gesprochen, und ihm, aus veneration, die Hände geküsset.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Wolff, Christoph (2000). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039304825X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Complete Organ Works (Reincken, Johann Adam): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)