Altenburg Abbey

Altenburg Abbey (German: Stift Altenburg) is a Benedictine monastery in Altenburg, Lower Austria. It is situated about 30 kilometres (19 mi) to the north of Krems an der Donau in the Waldviertel.[1] It was founded in 1144,by Countess Hildeburg of Poigen-Rebgau. Throughout its history it suffered numerous invasions and attacks, and was destroyed by the Swedes in 1645. Under Emperor Joseph II in 1793 the abbey was forbidden to accept new novices, but unlike many others in Austria it succeeded in remaining functional.

The abbey attained its present Baroque form under the direction of abbots Maurus Boxler and Placidus Much. The modernization of the abbey was supervised by the architect Josef Munggenast with support from some of the most distinguished artists and craftsmen of Austria: Paul Troger on the frescoes, Franz Josef Holzinger on the stucco work, and Johann Georg Hoppl on the marbling.[2][3] The Baroque structure which replaced the earlier Romanesque abbey is said to be one of the finest in Austria.[4]

History

Altenburg Abbey was founded in 1144[3] by Countess Hildeburg of Poigen-Rebgau. Archeological excavations carried out by the Federal Monuments Office between 1983 and 2005 have revealed evidence of its dating in the remains of a wall from the 12th century and of a Romanesque cloister dated to the 13th century. The monastery was destroyed and reconstructed as a result of numerous attacks. The first was in 1251 by Hermann V von Baden, followed by several by the Cumans between 1304 and 1327 and during the Hussite Wars from 1427 to 1430. It was attacked by Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary in 1448, and by the Turks in 1552. In 1327, some restoration work was carried out by Gertrude, the widow of Heidenreich von Gars.[2] In 1645, the Swedes destroyed the abbey.[4]

Refurbishment took shape after the Thirty Years' War in the 17th and 18th centuries. The abbey took its present form in the Baroque style under the abbots Maurus Boxler and Placidus Much. Work was carried out under the supervision of the architect Josef Munggenast who was assisted by some of Austria's most distinguished artists and craftsmen: Paul Troger for the frescoes, Franz Josef Holzinger for the stucco work, and Johann Georg Hoppl for the marbling.[2] Under Emperor Joseph II in 1793 the abbey was forbidden to accept new novices, but unlike many others in Austria it succeeded in remaining functional. Subsequent to the Revolution of 1848, its debts were cleared by the sale of some of the chapel's major artifacts.[2]

On 12 March 1938, Abbot Ambros Minarz refused to fly the Nazi's Swastika flag at the abbey which resulted in its occupation by the Sturmabteilung (a paramilitary organization of the Nazis SA) from 17 March 1938.[5] For a brief period between 1940–1941 under the National Socialists the abbey was suspended, and in 1941 dissolved. The abbot was placed under arrest and the community dispossessed.[2] From 1945 the premises were used as accommodation by Soviet occupying troops. Under Abbot Maurus Knappek (1947–1968) the buildings were restored and the community re-established.[2]

Since 1625, the abbey has been a member of the Austrian Congregation now within the Benedictine Confederation. Archeological excavations carried out in the chapel have revealed a medieval "monastery beneath the monastery". The finds include a refectory, a chapter house, the monks' working and living quarters, a cloister, a scriptorium, and a Gothic St. Vitus Chapel.[6][7]

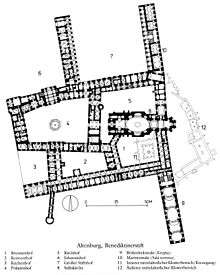

Layout plan

The abbey occupies a very large area with the front façade, which faces east, itself occupying a length of 200 m surrounded by a number of landscaped gardens.[1] The abbey complex has 12 identified areas of: 1. Fountain Court 2. Convent Court 3. Kitchen Court 4. Prelates Court 5. Church Court 6. Johann's Court 7. Great Abbey Court 8. Abbey Church 9. Library Wing (Crypt) 10. Marble Wing (Sala terrena) 11. Inner Medieval Monastery (Cloister) 12. Outer Medieval Monastery>[8]

Features

The abbey displays a fusion of Baroque and Rococo stucco architectural styles in its interiors. During the reconstruction, the library, imperial staircase and marble hall were added.[1] The staircase, abbey church and library are noted for the frescoes painted by Paul Troger. Those in the vestibule leading to the library are the work of his student, Johann Jakob Zeiller.[7]

The library, built in 1740, is of Baroque architectural elegance,[9] an imposing room that rises to three stories in height. The library hall is 48 m (157 ft) long and its ceiling is decorated with frescoes crafted by Paul Troger. Among the many frescoes, the distinctive ones are the Judgment of Solomon, the Wisdom of God and the Light of Faith.[1] Beneath the library is a large crypt which is also decorated with many frescoes by unknown artists; one particular scene which is fierce in appearance is that of the Dance of Death.[1]

The church is oval-shaped and bears a dome. It was renovated in 1730–33 by Joseph Munggenast. The dome is also decorated with Troger frescoes. The main feature of the altarpiece is a painting Assumption of Mary, topped by a representation of the Trinity.[1]

Gardens

In recent years, a number of well-tended gardens in different styles have been developed around the monastery. They were all planted by the monks themselves with assistance from the Natur im Garten project as well as from nurseries in the area.[7]

Once the abbey park, Der Garten der Religionen (the Garden of Religions) is the largest of the gardens. It was recently used for growing Christmas trees and fruit trees. The garden now consists of five landscaped areas dedicated to the world's five main religions – Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It also has a large natural pond surrounded by a meadow full of wild flowers, a group of trees, and the old plum grove where the local livestock can be seen. There is also an apple tree area reflecting the "monastery under the monastery" theme.[7]

Der Apothekergarten (the Apothecary Garden) on the eastern side of the monastery has been developed on the spot where there once used to be a garden of herbs which were used for medicinal purposes in the Middle Ages. The present garden has been developed along more modern lines of horticultural science.[7]

Der Schöpfungsgarten (the Garden of Creation) has been developed on the southern part of the abbey church where the Source Garden used to be. The theme of the park is theological: the story of the creation. There is a bench under the large walnut tree which has been cited as one of the best spots to be on a hot summer's day.[7]

Der Garten der Stille (the Garden of Tranquillity), the most recent addition, has been developed to the east where there used to be a game reserve. It is a naturally landscaped garden consisting of an orchard, a vineyard, an area for butterflies, insect hives and a hobby garden. There are 11 stone sculptures by Eva Vorpagel-Redl that are fixed at strategic locations along paths which lead to the forest area. There is also a platform here which provides views of the impressive eastern facade of the chapel and the eastern part of the medieval monastery.[7]

Der Kreuzganggarten is simply the cloister garden.[7]

Gallery

Main entrance

Main entrance Prelature

Prelature Exterior view of abbey and gardens

Exterior view of abbey and gardens Interior view

Interior view Interior view

Interior view Frescoes over the imperial staircase

Frescoes over the imperial staircase- Crypt below the library

References

- Taylor & Eisenschmid 2009, p. 181.

- "Kloster-Geschichte" (in German). Official Website of Altenburg Abbey website. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Lonely Planet review for Stift Altenburg". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Erk & Erk 2012, p. 146.

- MacDonogh 2009, p. 65.

- Taylor & Eisenschmid 2009, pp. 181–82.

- "Stiftsbesichtigung:Es gibt viel zu sehen im Stift Altenburg!" (in German). Official Website of Altenburg Abbey website. Archived from the original on 2013-03-22. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Image of Stift Altenburg Grundriss". Translation of Legend in the image: 1. Fountain Court, 2. Convent Court, 3. Kitchen Court, 4. Prelates Court, 5. Church Court, 6. Johann's Court, 7. Great Abbey Court, 8. Abbey Church, 9. Library Wing (Crypt), 10. Marble Wing (Sala terrena), 11. Inner Medieval Monastery (Cloister), 12. Outer Medieval Monastery (in German). Wikicommons. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Aston 2002, p. 45.

- Bibliography

- Aston, Nigel (2002). Christianity and Revolutionary Europe, 1750–1830. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46592-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erk, Phil; Erk, Nan (March 2012). The Overcomers. Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-61996-844-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDonogh, Giles (1 December 2009). 1938: Hitler's Gamble. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02012-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Robert; Eisenschmid, Rainer (2009). Austria. Baedeker. ISBN 978-3-8297-6613-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stift Altenburg. |

- Altenburg Abbey website (in German)