Alpheidae

Alpheidae is a family of caridean snapping shrimp, characterized by having asymmetrical claws, the larger of which is typically capable of producing a loud snapping sound. Other common names for animals in the group are pistol shrimp or alpheid shrimp.

| Alpheidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Alpheus digitalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Order: | Decapoda |

| Superfamily: | Alpheoidea |

| Family: | Alpheidae Rafinesque, 1815 |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

The family is diverse and worldwide in distribution, consisting of about 1,119species within 38 or more genera.[1] The two most prominent genera are Alpheus and Synalpheus, with species numbering well over 250 and 100, respectively.[2][3] Most snapping shrimp dig burrows and are common inhabitants of coral reefs, submerged seagrass flats, and oyster reefs. While most genera and species are found in tropical and temperate coastal and marine waters, Betaeus inhabits cold seas and Potamalpheops is found only in freshwater caves.

When in colonies, the snapping shrimp can interfere with sonar and underwater communication. The shrimp are considered a major source of noise in the ocean.[4]

Description

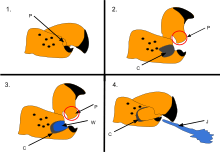

The snapping shrimp grows to only 3–5 cm (1.2–2.0 in) long. It is distinctive for its disproportionate large claw, larger than half the shrimp's body. The claw can be on either arm of the body, and, unlike most shrimp claws, does not have typical pincers at the end. Rather, it has a pistol-like feature made of two parts. A joint allows the "hammer" part to move backward into a right-angled position. When released, it snaps into the other part of the claw, emitting an enormously powerful wave of bubbles capable of stunning larger fish and breaking small glass jars.[5]

Ecology

Some pistol shrimp species share burrows with goby fishes in a mutualistic symbiotic relationship. The burrow is built and tended by the pistol shrimp, and the goby provides protection by watching out for danger. When both are out of the burrow, the shrimp maintains contact with the goby using its antennae. The goby, having the better vision, alerts the shrimp of danger using a characteristic tail movement, and then both retreat into the safety of the shared burrow.[6] So far this association has been observed in species that inhabit coral reef habitats.

Eusocial behavior has been discovered in the genus Synalpheus. The species Synalpheus regalis lives inside sponges in colonies that can number over 300 members.[7] All of them are the offspring of a single large female, the queen, and possibly a single male. The offspring are divided into workers who care for the young and predominantly male soldiers who protect the colony with their huge claws.[7]

Pistol shrimp have also been noted for their ability to reverse claws. When the snapping claw is lost, the missing limb will regenerate into a smaller claw and the original smaller appendage will grow into a new snapping claw. Laboratory research has shown that severing the nerve of the snapping claw induces the conversion of the smaller limb into a second snapping claw. This phenomenon of claw symmetry in snapping shrimp has only been documented once in nature.[8]

Snapping effect

The snapping shrimp competes with much larger animals such as the sperm whale and beluga whale for the title of loudest animal in the sea. The animal snaps a specialized claw shut to create a cavitation bubble that generates acoustic pressures of up to 80 kPa at a distance of 4 cm from the claw. As it extends out from the claw, the bubble reaches speeds of 100 km/h (62 mph) and releases a sound reaching 218 decibels. The pressure is strong enough to kill small fish.[9] It corresponds to a zero to peak pressure level of 218 decibels relative to one micropascal (dB re 1 μPa), equivalent to a zero to peak source level of 190 dB re 1 μPa m. Au and Banks measured peak to peak source levels between 185 and 190 dB re 1 μPa m, depending on the size of the claw.[10] Similar values are reported by Ferguson and Cleary.[11] The duration of the click is less than 1 millisecond.

The snap can also produce sonoluminescence from the collapsing cavitation bubble. As it collapses, the cavitation bubble reaches temperatures of over 8,000 K (7,700 °C).[12] In comparison, the surface temperature of the sun is estimated to be around 5,772 K (5,500 °C).[13] The light is of lower intensity than the light produced by typical sonoluminescence and is not visible to the naked eye. It is most likely a by-product of the shock wave with no biological significance. However, it was the first known instance of an animal producing light by this effect. It has subsequently been discovered that another group of crustaceans, the mantis shrimp, contains species whose club-like forelimbs can strike so quickly and with such force as to induce sonoluminescent cavitation bubbles upon impact.[14]

The snapping is used for hunting (hence the alternative name "pistol shrimp"), as well as for communication. When hunting, the shrimp usually lies in an obscured spot, such as a burrow. The shrimp then extends its antennae outwards to determine if any fish are passing by. Once it feels movement, the shrimp inches out of its hiding place, pulls back its claw, and releases a "shot" which stuns the prey; the shrimp then pulls it to the burrow and feeds on it.

When in colonies, the snapping shrimp can interfere with sonar and underwater communication.[4][15][16] The shrimp are a major source of noise in the ocean[4] and can interfere with anti-submarine warfare.[17][18]

Genera

More than 620 species are currently recognised in the family Alpheidae, distributed among 45 genera. The largest of these are Alpheus, with 283 species, and Synalpheus, with 146 species.[19]

- Acanthanas Anker, Poddoubtchenko & Jeng, 2006

- Alpheopsis Coutière, 1896

- Alpheus Fabricius, 1798

- Amphibetaeus Coutière, 1896

- Arete Stimpson, 1860

- Aretopsis De Man, 1910

- Athanas Leach, 1814

- Athanopsis Coutière, 1897

- Automate De Man, 1888

- Bannereus Bruce, 1988

- Batella Holthuis, 1955

- Bermudacaris Anker & Iliffe, 2000

- Betaeopsis Yaldwyn, 1971

- Betaeus Dana, 1852

- Bruceopsis Anker, 2010

- Coronalpheus Wicksten, 1999

- Coutieralpheus Anker & Felder, 2005

- Deioneus Dworschak, Anker & Abed-Navandi, 2000

- Fenneralpheus Felder & Manning, 1986

- Harperalpheus Felder & Anker, 2007

- Jengalpheops Anker & Dworschak, 2007

- Leptalpheus Williams, 1965

- Leptathanas De Grave & Anker, 2008

- Leslibetaeus Anker, Poddoubtchenko & Wehrtmann, 2006

- Metabetaeus Borradaile, 1899

- Metalpheus Coutière, 1908

- Mohocaris Holthuis, 1973

- Nennalpheus Banner & Banner, 1981

- Notalpheus G. Méndez & Wicksten, 1982

- Orygmalpheus De Grave & Anker, 2000

- Parabetaeus Coutière, 1896

- Pomagnathus Chace, 1937

- Potamalpheops Powell, 1979

- Prionalpheus Banner & Banner, 1960

- Pseudalpheopsis Anker, 2007

- Pseudathanas Bruce, 1983

- Pterocaris Heller, 1862

- Racilius Paul’son, 1875

- Richalpheus Anker & Jeng, 2006

- Rugathanas Anker & Jeng, 2007

- Salmoneus Holthuis, 1955

- Stenalpheops Miya, 1997

- Synalpheus Bate, 1888

- Thuylamea Nguyên, 2001

- Triacanthoneus Anker, 2010

- Vexillipar Chace, 1988

- Yagerocaris Kensley, 1988

References

- A. Anker; S. T. Ahyong; P. Y. Noel; A. R. Palmer (2006). "Morphological phylogeny of alpheid shrimps: parallel preadaptation and the origin of a key morphological innovation, the snapping claw". Evolution. 60 (12): 2507–2528. doi:10.1554/05-486.1. PMID 17263113.

- W. Kim; L. G. Abele (1988). "The snapping shrimp genus Alpheus from the Eastern Pacific (Decapoda: Caridea: Alpheidae)". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 454 (454): 1–119. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.454.

- Fenner A. Chace, Jr. (1988). "The Caridean Shrimps (Crustacea: Decapoda) of the Albatross Philippine Expedition, 1907–1910, Part 5: Family Alpheidae" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 466: 1–99.

- "Shrimp, bubble and pop". BBC News. September 21, 2000. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- Maurice Burton; Robert Burton (1970). The International Wildlife Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Marshall Cavendish. p. 2366.

- I. Karplus (1987). "The association between gobiid fishes and burrowing alpheid shrimps". Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. 25: 507–562.

- J. E. Duffy (1996). "Eusociality in a coral-reef shrimp". Nature. 381 (6582): 512–514. doi:10.1038/381512a0.

- M. R. McClure (1996). "Symmetry of large claws in snapping shrimp in nature (Crustacea: Decapoda: Alpheidae)". Crustaceana. 69 (7): 920–921. doi:10.1163/156854096X00321.

- M. Versluis; B. Schmitz; A von der Heydt; D. Lohse (2000). "How snapping shrimp snap: through cavitating bubbles". Science. 289 (5487): 2114–2117. doi:10.1126/science.289.5487.2114. PMID 11000111.

- W. W. L. Au; K. Banks (1998). "The acoustics of the snapping shrimp Synalpheus parneomeris in Kaneohe Bay". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 103 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1121/1.423234.

- B. G. Ferguson; J. L. Cleary (2001). "In situ source level and source position estimates of biological transient signals produced by snapping shrimp in an underwater environment". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 109 (6): 3031–3037. doi:10.1121/1.1339823. PMID 11425145.

- D. Lohse; B. Schmitz; M. Versluis (2001). "Snapping shrimp make flashing bubbles". Nature. 413 (6855): 477–478. doi:10.1038/35097152. PMID 11586346.

- Williams, D.R. (1 July 2013). "Sun Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- S. N. Patek; R. L. Caldwell (2005). "Extreme impact and cavitation forces of a biological hammer: strike forces of the peacock mantis shrimp" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 208 (19): 3655–3664. doi:10.1242/jeb.01831. PMID 16169943.

- Kenneth Chang (September 26, 2000). "Sleuths solve case of bubble mistaken for a snapping shrimp". The New York Times. p. 5. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- "Sea creatures trouble sonar operators – new enzyme". The New York Times. February 2, 1947. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- Stuart Rock. "Submarine hunting in Somerset" (PDF). thalesgroup.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.]

- "Underwater Drones Join Microphones to Listen for Chinese Nuclear Submarines - AUVAC". auvac.org. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Sammy De Grave; N. Dean Pentcheff; Shane T. Ahyong; et al. (2009). "A classification of living and fossil genera of decapod crustaceans" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. Suppl. 21: 1–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Alpheidae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alpheidae. |

- How snapping shrimp snap, University of Twente

- Article on pistol shrimp going into physical details

- Radiolab Podcast: Bigger Than Bacon The history and science of snapping shrimp for children and adults