Alfred Horace Gerrard

Alfred Horace "Gerry" Gerrard RBS (7 May 1899 – 13 June 1998) was an English modernist sculptor. He was head of the sculpture department at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1925 and professor of sculpture there from 1949 to 1968, where he taught a number of well-known sculptors.

Alfred Horace Gerrard | |

|---|---|

| Born | 7 May 1899 Hartford, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 13 June 1998 (aged 99) Groombridge, Kent, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Manchester School of Art Slade School of Fine Art |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Notable work | Memorial Stone for a Hunter North Wind Stages in the Development of Man The Dance |

| Movement | Modernism |

| Awards | RBS Silver Medal, 1960 |

Early life

Gerrard was born on 7 May 1899 in Hartford, Cheshire where his family had been farming for four centuries. He was the youngest of five children and was directly descended from the 16th century herbalist John Gerard. Gerrard was educated at Northwich Technical School which he left in 1916.[1]

During the First World War, he served in the army with the Cameron Highlanders, the Black Watch and the Gordon Highlanders and in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) from 1917.[1][2] In the RFC, Gerrard flew Farman MF.11s and F.E.2Bs as a night bomber pilot, crashing and injuring his back on one occasion when his undercarriage fell off.[1]

Career

After being demobilized Gerrard studied at the Manchester School of Art in 1919 and at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1920 where Henry Tonks was his teacher and contemporaries included Samuel Rabinovitch.[1] In 1925, Tonks appointed Gerrard head of the school's sculpture department,[1] a position he held until 1948 after which he was Professor of Sculpture until 1968 and then Emeritus Professor.[2] In the 1920s, Gerrard elected to wear a standard set of clothes – sports jacket, corduroy trousers, a collarless shirt and a yellow stock. He bought multiple copies of these items and wore them regularly for decades.[1]

During the Second World War, Gerrard was a Staff Captain attached to the Royal Engineers working on camouflage projects.[1][2] Following a plane crash in which he was badly injured, he almost had an arm amputated, but persuaded his doctors to save it so that he could continue sculpting.[1]

In a long teaching career, Gerrard taught and influenced numerous artists, among them Kenneth Armitage, Karin Jonzen, Eduardo Paolozzi and F. E. McWilliam.[2][3] In the austerity years after the Second World War, Gerrard kept the school supplied with raw materials for sculpting by salvaging stone, wood and metal from bomb sites.[1] Well respected for his expertise as a teacher and his generosity, many of his former students would visit him at his home in Kent where he continued sculpting into his eighties.[1]

Whilst teaching at the Slade, Gerrard received private sculpture commissions, often executed on a large scale in stone, as well as producing murals for ocean liners. He also worked as a book illustrator with his future wife Katherine Leigh-Pemberton, producing wood cuts for Elephants and Ethnologists (by Grafton Elliot Smith) and Egyptian Mummies (by Smith and Warren Royal Dawson) in 1924 and for the Book of Bath in 1925. During 1944–45 he worked as a war artist.[1]

Among his sculptural works are:

- Memorial Stone for a Hunter, 1926. Displayed temporarily at the Tate Gallery before its final installation.[4]

- North Wind, 1928–29. One of eight personifications of the four winds commissioned by Charles Holden and Frank Pick for the headquarters of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London at 55 Broadway.[note 1]

- St Anselm, 1933, St Anselm's church, Kennington Cross.[6]

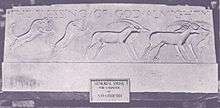

- Monumental Parcel, gilded carved wooden panels of horses in a forest for RMS Britannic.

- Stages in the Development of Man, 1955, four wall panels built into the end façade of a building in Hemel Hempstead.[7]

- The Dance, 1960, a sculpture wall for which he was awarded the Royal British Society of Sculptors' Silver medal.[1]

An exhibition of his work was staged at the South London Art Gallery in 1978.[1] Collections that contain work by Gerrard include the Tate Gallery,[8] and the Imperial War Museum. The Henry Moore Institute archive contains works by Gerrard and his papers.[9]

Family

Gerrard married three times:[2]

- 1933, Katherine Leigh-Pemberton (died 1970)

- 1972, Nancy Sinclair (died 1995)

- 1995, Karen Sinclair

He had no children.

Notes and references

Notes

- Other sculptors to provide works for the building included Jacob Epstein, Henry Moore, Eric Gill, Eric Aumonier, Allan G Wyon and Samuel Rabinovitch.[5]

References

- Buckman 1998.

- Who Was Who 2007.

- "About F. E. McWilliam". F. E. McWilliam Gallery & Studio. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- "A Memorial Stone: Sculptor's Work at the Tate Gallery". The Times (44317). 7 July 1926. p. 11. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "55 Broadway". Exploring 20th Century London. London Museums Hub. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "Picture Gallery". The Times (46518). 9 August 1933. p. 14. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "Picture Gallery". The Times (53398). 8 December 1955. p. 3. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "Eternal Life". Tate Gallery. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- "Archive catalogue". Henry Moore Institute. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Buckman, David (30 June 1998). "Obituary: A. H. Gerrard". The Independent. Retrieved 4 June 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Gerrard, Prof. Alfred Horace". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press/A & C Black. 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred Horace Gerrard. |