Alexis Soyer

Alexis Benoît Soyer (4 February 1810 – 5 August 1858) was a French chef who became the most celebrated cook in Victorian England. He also tried to alleviate suffering of the Irish poor in the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), and contributed a penny for the relief of the poor for every copy sold of his pamphlet The Poor Man's Regenerator (1847). He worked to improve the food provided to British soldiers in the Crimean War. A variant of the field stove he invented at that time, known as the "Soyer stove", remained in use with the British army until 1982.[1][2]

Alexis Soyer | |

|---|---|

Alexis Soyer in 1849 | |

| Born | Alexis Benoist Soyer 4 February 1810 Meaux-en-Brie, France |

| Died | 5 August 1858 (aged 48) London, England |

| Resting place | Kensal Green Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | chef, author, inventor |

Notable work | Soyer stove |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Emma Jones |

| Children | 2 |

Biography

Alexis Benoît (aka Bénoist) Soyer was born to Emery Roche Soyer and his wife, Marie Chamberlan, at Meaux-en-Brie in France. The family had arrived in Meaux in 1799, on the advice of a relative employed as a notary in the town and attracted by its reputation as a stronghold of the Huguenot, or French Calvinist, community.[3]

His father had several jobs, one of them as a grocer. There is little concrete evidence of Soyer's early life[4] but according to François Volant, later his secretary and biographer, Soyer was sent by his parents at the age of nine to the Protestant seminary, as they had destined him for the ordained ministry. Volant claims that Soyer resented the career path chosen for him and, after complaining to his parents, contrived his own dismissal.[5] This cannot be entirely accurate, as his father died in Condé-Sainte-Libiaire, France, 20 August 1818. Alexis would be 8 years when his father died.[6] Volant implicitly dates his expulsion from the seminary to 1820. Cowen points out that "there are no surviving records of his enrolment in any school." A year later, in 1821, he was sent to Paris to live with his elder brother, Philippe. He became an apprentice at the restaurant of Georg Rignon in the Rue Vivienne, close to the Passage des Panoramas. Later, the Rignon moved west to the Boulevard des Italiens, very close to the Café Anglais. In 1826 Soyer left to join the Maison Douix, an enormous restaurant further along the Boulevard des Italiens, where he became a chief cook within a year, heading a team of twelve, known as his Brigade of Cooks. By 1830, Soyer was a second cook to Jules, Prince de Polignac, who was the French prime minister under Charles X.

On 26 July 1830, while assisting in the kitchens of Polignac, armed supporters of "Les Trois Glorieuses" burst in and shot two of the staff.[7] Soyer escaped, and then fled to England where he joined the London household of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, where his brother Philippe was head chef. He then worked for various other British notables. He moved in 1832 to work as sous-chef for Henry Beresford, 3rd Marquess of Waterford, a notorious drunk and brawler.[8] He soon moved to the household of George Leveson-Gower, 2nd Marquess of Stafford and Elizabeth Sutherland, 19th Countess of Sutherland, who were to become Duke and Duchess of Sutherland in the following year, 1833. However, the Duke died in July of that year, leaving the family's London home, Stafford House as a base for his daughter-in-law, Harriet, a glamorous Whig hostess and promoter of liberal causes: she was to remain an important friend and supporter of Soyer throughout his life.[9]

Soyer remained in the employment of the Leveson-Gower family for only a short time, moving to take charge of the kitchens of William and Louisa Lloyd, who owned three large properties around Oswestry in north Shropshire: Aston Hall, Whittington Castle and Chigwell House. Soyer worked for the Lloyds for more than three years, becoming well known among the Shropshire landed gentry, who vied to lure him away from the Lloyds or, at least, to borrow his services for important occasions.[10] During his employment with the Lloyds he decided to have his portrait painted by François Simonau, a Belgian painter and teacher. Through Simonau he met a pupil, Elizabeth Emma Jones,[11] whom he was to marry in 1837. Soyer left the Lloyds in the spring of 1836 to take over the kitchens of Archibald Kennedy, 1st Marquess of Ailsa at St Margaret's House near Twickenham, a large Thames-side residence that subsequently gave its name to its entire suburb. Ailsa also had a central London base at Privy Gardens in Whitehall. A gourmet and a consistent supporter of Whig reforming legislation in the House of Lords, Ailsa was a prominent freemason and it is possible that it was he who introduced Soyer to the craft, which he pursued for the rest of his life.[12] Ailsa took a very active interest in the kitchen, discussing menus in detail with Soyer, and was to remain a long-term friend. Soyer left Ailsa to take up a position as head chef of the Reform Club from 1837 to 1850, where he designed the innovative kitchens.

His wife, generally known simply as Emma Jones, achieved considerable popularity as a painter, chiefly of portraits. She was one of the youngest persons to exhibit at the Royal Academy; in 1823, at the age of 10, she submitted the Watercress Woman. Her portrait of Soyer was engraved by Henry Bryan Hall.[13] She died in 1842 following complications suffered in a premature childbirth brought on by a thunderstorm. Distraught, Soyer erected a monument to her at Kensal Green Cemetery, London.

Soyer died on 5 August 1858. At the time of his death, he was designing a mobile cooking carriage for the British Army. On 11 August, he was buried beside his wife in Kensal Green Cemetery.[14]

Innovations

In 1837 Soyer became chef de cuisine at the Reform Club in London.[15] He designed the kitchens with Charles Barry at the newly built Club, where his salary was to be more than £1,000 a year. He instituted many innovations, including cooking with gas, refrigerators cooled by cold water, and ovens with adjustable temperatures. His kitchens were so famous that they were opened for conducted tours. When Queen Victoria was crowned on 28 June 1838, he prepared a breakfast for 2,000 people at the Club. Soyer's eponymous Lamb Cutlets Reform are still on the Club menu. Soyer was an able self-promoter. "Soyer's Sultana's Sauce" was marketed for him through Crosse & Blackwell in an exotic bottle with a label featuring Soyer himself, unmistakable in his trademark cocked hat.[16]

During the Great Irish Famine in April 1847, he invented a soup kitchen and was asked by the Government to go to Ireland to implement his idea. This was opened in Dublin and his "famine soup" was served to thousands of the poor for free. Unfortunately for the starving Irish, this selection by the Government was primarily based on low cost of the ingredients of the soups Soyer proposed, rather than on their nutritional value.[17] While in Ireland he wrote Soyer's Charitable Cookery. He gave the proceeds of the book to various charities. He also opened an art gallery in London, and donated the entrance fees to charity to feed the poor.

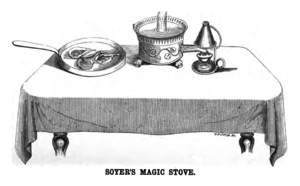

In 1849 Soyer began to market his "magic stove" which allowed people to cook food wherever they were. It was designed to be a tabletop stove.

Soyer resigned from the Reform Club in May 1850. Knowing that the Great Exhibition was going to be staged he submitted a design for it, which was not accepted. The Reform Club member Joseph Patton was awarded the job for his Glass House. He had one of his friends, George Warrener, exhibit his Osmazone soup. He was also offered the drink and beverage franchise but turned it down. Instead he opened, in 1851, his Gastronomic Symposium of All Nations[19][20] in Gore House opposite the gates of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, a site now occupied by the Royal Albert Hall. Prior to its grand opening on 17 May 1851, on 15 May a banquet was held to which every European newspaper had been invited. Later that year Soyer was forced to close his great venture after losing £7,000.

Soyer wrote a number of books about cooking, possibly with assistance. His 1854 book A Shilling Cookery for the People[21] was a recipe book for ordinary people who could not afford elaborate kitchen utensils or large amounts of exotic ingredients.

During the Crimean War, Soyer joined the troops at his own expense to advise the army on cooking. Later he was paid his expenses and wages equivalent to those of a Brigadier-General. He reorganized the provisioning of the army hospitals. He designed his own field stove, the Soyer Stove, and trained and installed in every regiment the "Regimental cook" so that soldiers would get an adequate meal and not suffer from malnutrition or die of food poisoning. He wrote A Culinary Campaign as a record of his activities in the Crimea. Catering standards within the British Army would remain inconsistent, however, and there would not be a single Army Catering Corps until 1945. This is now part of the Royal Logistic Corps, whose catering HQ is called Soyer's House. His stove, or adaptions of it, remained in British military service as late as Gulf War One.[22] Soyer returned to London on 3 May 1857[23] and on 18 March 1858, he lectured at the United Service Institution on army cooking.[24] He also built a model kitchen at the Wellington Barracks in London.[25]

In popular culture

Soyer, his cooking, the kitchen at the Reform Club, and so on are setting for the murder mystery The Devil's Feast, by M.J. Carter.[26]

Works

British Army catering officers still hold an annual dinner at their new home in Worthy Down, Winchester. Army chefs usually design the menu using Soyer's old recipes. Sources include:

- Culinary Relaxtion. (1845) Simpkin & Marshall. London, England

- Délassements Culinaires. (1845)

- The Gastronomic Regenerator (1846)

- Soyer's Charitable Cookery (1847)

- The Poor Man's Regenerator (1848)

- The modern Housewife or ménagère (1849)[27]

- The Pantropheon: Or, History of Food and Its Preparation : from the Earliest Ages of the World. Ticknor, Reed, and Fields. 1853.

- A Shilling Cookery Book for the People (1855).

- Soyer's Culinary Campaign (1857).

- Memoirs of Alexis Soyer (1859).

Further reading

- Mary Delorme - Alexis (1986). London: Robert Hale ISBN 0-7090-2406-1. Ulverscroft large print version (1992) ISBN 0-7089-2659-2

- Helen Morris – Portrait of a Chef the Life of Alexis Soyer Sometime Chef to the Reform Club (1938). Republished by Cambridge Library Collection (2013), ISBN 978-11-080616-9-8

- Frank J Clement-Lorford – Alexis Soyer; The First Celebrity Chef (2001– Available as an e-book on Amazon

- Ann Arnold – Adventurous Chef: Alexis Soyer (2002) ISBN 0-374-31665-1

- Ruth Brandon – The People's Chef: Alexis Soyer, A Life in Seven Courses (2004) ISBN 0-470-86991-7

- Ruth Cowen – Relish: The Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef (2006) ISBN 0-297-64562-5

- Kyle – " Alexis Soyer: The Pantropheon: Or A History of Food And Its Preparation in Ancient Times" (2001) ISBN 1-58963-359-8

- Thomas A P Van Leeuwen- The Magic Stove: Barry, Soyer and The Reform Club or How a Great Chef Helped to Create a Great Building (2017) ISBN 978-90-826690-0-8

References

- "Forgotten history – Soyer's Stoves". 21 September 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- An online biographical profile is Michael Garval "Romantic Gastronomies: Alexis Soyer and the Rise of the Celebrity Chef"

- Cowen, Ruth (2006). Relish: the Extraordinary Life of Alexis Soyer, Victorian Celebrity Chef. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 10–11.

- Cowen, p. 12.

- F. Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 2.

- Frank Clement-Lorford

- F.Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 6.

- Cowen, p. 19–20.

- Cowen, p. 21.

- Cowen, p. 24–25.

- Cowen, p. 26–27.

- Cowen, p. 28–29.

- "NPG D6822; Alexis Benoît Soyer". Portrait. National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Paths of Glory. Friends of Kensal Green Cemetery. 1997. p. 93.

- F. Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 22.

- Illustrated in Garval, fig 11

- As already indicated at that time in the Lancet as soup quackery

- Alexis Soyer (1851). The Modern Housewife: Or, Ménagère. Comprising Nearly One Thousand Receipts... Simpkin, Marshall, & Co.

- "Reform Club". www.reformclub.com. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Bullock, April (2005). "Alexis Soyer's Gastronomic Symposium of All Nations". Gastronomica. 5 (4): 50–59. doi:10.1525/gfc.2005.5.4.50. ISSN 1529-3262.

- "A shilling cookery for the people". 7 August 1854. Retrieved 7 August 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Andrew Marr (3 January 2019). Andrew Marr's History of Modern Britain (television documentary). BBC.

- F. Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 267.

- F. Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 272.

- F. Volant; J.R. Warren, eds. (1859). Memoirs of Alexis Soyer: With Unpublished Receipts and Odds and Ends of Gastronomy. W.Kent & Co. p. 274.

- Carter, M.J. (2017) The Devil's feast. (G.P. Putnam's sons). ISBN 9780399171697

- (accessed March 17, 2012). Worldcat.org. OCLC 252570657.

- Attribution

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–525.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Alexis Benoit Soyer. |

![]()

- Website about Soyer

- Works by Alexis Soyer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alexis Soyer at Internet Archive

- Works by Alexis Soyer at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lamb Cutlets Reform recipe