Alexandru Bassarab

Alexandru Bassarab, or Basarab (August 7, 1907 – July 8, 1941), was a Romanian painter, engraver, and fascist politician. Earning his reputation for his pioneering work in linocut and woodcut, he explored neotraditionalism, Romanian nationalism, and Romanian folklore, and was ultimately drawn into politics with the Iron Guard. He helped steer several art groups associated or integrated with the Guard, contributed to its fascist propaganda, and briefly served in the Assembly of Deputies. He survived the clampdown of the late 1930s, returning to apolitical work with Grupul Grafic, and exploring the legacy of Byzantine art.

Alexandru Bassarab | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait | |

| Born | August 7, 1907 |

| Died | July 8, 1941 (aged 33) Țiganca (presumed) |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Education | National School of Fine Arts (presumed) |

| Known for | Linocut, woodcut, line engraving, illustration, typography, oil painting |

| Movement | Arta și Omul Grupul Grafic |

Under the National Legionary State, Bassarab returned to favor as one of the leading political iconographers, also urging others to contribute "epic" art in support of the regime. Arrested during the civil strife of early 1941, Bassarab was allowed to redeem himself on the Eastern Front. He died there, in mysterious circumstances, while his work continued to be censored at home.

Biography

Early life

Bassarab was born in Bacău, where he graduated high school.[1] Likely a student of Ion Theodorescu-Sion's at the National School of Fine Arts, in subsequent years he attended both the Law Faculty of the University of Bucharest at the private art school run by Constantin Vlădescu, where his teachers included Nicolae Tonitza, Francisc Șirato and Petre Iorgulescu-Yor.[2] Bassarab was a specialist in the linocut technique,[3] also praised for his work in woodcut. He continued to exhibit canvasses at various venues but, as noted at the time by art critic Alexandru D. Broșteanu, these were "timid", far less "rounded" than his woodcuts.[4] The same was argued by Petru Comarnescu, who suggests that Bassarab "never fully mastered the interplay of colors".[5]

Bassarab joined the Iron Guard, a native fascist movement, in 1932, and, as an aspiring propagandist, helped set up its artistic club, named after Ștefan Luchian, and its Ideea României Lodge.[1] From October 1934, with Ioan Victor Vojen, Dan Botta, Alexandru Ciucurencu, Radu Gyr, Horia Stamatu, and George Zlotescu, Bassarab was also active in the art collective Arta și Omul. Founded as an apolitical enterprise by Tonitza, it had been taken over by Guardist intellectuals, expressing its rejection of liberal democracy and its embrace of corporatism.[6] In parallel, Bassarab's apolitical works were featured at the Official Salons. Although he failed to win prizes there, in 1934 and 1935 the Romanian state purchased a number of his engravings.[7] With Stamatu, he worked on an edition of François Villon's ballads: Stamatu translated them, and Bassarab designed the lettering. Although the work was never printed in book form, it circulated as a rough copy among the intellectuals of Bucharest.[8]

According to historian Roland Clark, Bassarab and Zlotescu endure as "[the Guard's] best painters", both of them being guided by Theodorescu-Sion's neotraditionalism; all three were indebted to Romanian folklore, depicting peasants as "active, heroic figures", "dynamic, virile, determined".[9] Their art, seen by far-right chroniclers as a "purely Romanian" enterprise, was prominently displayed at the Guard's Bucharest offices, Casa Verde, during a September 1937 exhibit.[10] Mihail Polihroniade used Bassarab's engravings for his propaganda work, Tabăra de muncă, which came out at Universul publishers in 1936.[11] In 1937, Bassarab and Zlotescu also illustrated Neculai Totu's memoir of Guardist participation in the Spanish Civil War.[12]

Bassarab ran on the Guard lists in the December 1937 election. He took a seat in the Assembly of Deputies for Ialomița, but lost it immediately when King Carol II ordered a clampdown.[1] Subsequently, the National Renaissance Front dictatorship kept Bassarab under close watch, documenting his participation (with Polihroniade, Ion Zelea Codreanu, and Bănică Dobre) in the clandestine Guardist reunion of Călărași (February 1938).[13] By early 1940, Bassarab exhibited with the collective known as Grupul Grafic, alongside Marcel Olinescu. Their work was apolitical, heavily inspired by Byzantine art—within that context, Bassarab remained the more naturalistic, preserving elements of perspective.[14] Founders of Grupul Grafic also included Aurel Mărculescu, who was both Jewish and an anti-fascist.[15]

Political rise, downfall, and death

In September 1940, Carol abdicated and the Guard took over, establishing a "National Legionary State"; Bassarab, Olinescu, and Gheorghe Ceglokoff reformed Grupul Grafic, which was now openly associated with the Guard, and exhibited at Sala Dalles.[16] Bassarab exhibited work that was highly political, including portraits of folk heroes such as Horia alongside Guard commanders such as Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, Ion Moța and Gheorghe Clime. Ion Frunzetti, a Guard supporter and art critic, praised him as "the chronicler of a destiny", with "a certain Thracian toughness".[16][17] Appointed to high positions in the field of propaganda, Bassarab stirred controversy by suggesting that artists should abandon easel painting in favor of "epic" muralism.[18]

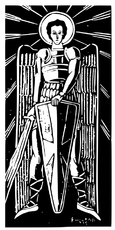

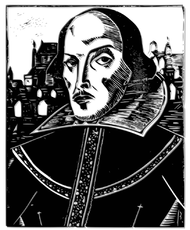

During that interval, the Guard accorded its assassinated and exhumed founder, Codreanu, a lavish second funeral. The ceremony was held at Sfântul Ilie Gorgani Church in Bucharest, and the entrance to the church was flanked by two giant posters of archangels, massively enlarged versions of line engravings drawn by Bassarab in 1935.[19] These closely resemble Nașterea ("Birth"), another drawing by Bassarab. There, the Guard's patron, the Archangel Michael, watches over an infant at his feet. Above, a legend gives Codreanu's birthdate, giving the image a religious and propagandistic impact. Another drawing of his draws upon folklore to place Codreanu in the context of the Miorița legend.[20] In December 1940, Bassarab organized an exhibit, Munca legionară ("Legionary Labor"), also at Sala Dalles, which represented a fusion of art with Guardist ideology.[21] It was attended by Traian Brăileanu, the Arts Minister, and Guard Commander Horia Sima.[22]

Soon afterwards, the Guard fell from power, and Bassarab was arrested on orders from Conducător Ion Antonescu.[1] When Romania entered World War II in June 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa, Bassarab was placed into a frontline unit with a high risk of casualties, participating in the recovery of Bessarabia. He vanished outside Țiganca. Legends began circulating that he had been killed while demining a field with his bare hands.[1] Another account has it that he had been taken prisoner by the Red Army, detained at Chișinău, and finally slashed with a bayonet when he protested against the torturing of a Romanian officer.[23] The most likely version is that he was captured and shot at Țiganca, in retaliation for the Romanians' treatment of Soviet prisoners.[1][24]

An obituary by Comarnescu saw print in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, praising Bassarab as the "laborer-artist" who, in dying, lived up to his "heroic perspective on art": "it was given to him that he should accomplish more as a Romanian soldier than as an artist, his very sound debut notwithstanding."[5] Bassarab's propaganda work was formally banned soon after Antonescu's downfall, as the new democratic regime and the Allied Commission clamped down on all forms of fascist literature and art.[12] His widow, who had a degree in philology, never remarried. She survived the rise and fall of Communist Romania and died in 1999 at age 95. Their son Șerban, born in 1940, pursued a career as a mathematician.[25] His father's work was again explored after the Romanian Revolution of 1989. In 1999, Petre Oprea republished art chronicles by Bassarab, Stamatu and Zlotescu, noting that their aesthetic hierarchies were often confirmed by posterity.[26]

Selected works

Primăvară pe cheiul Dâmboviței ("Spring on the Dâmbovița", 1934)

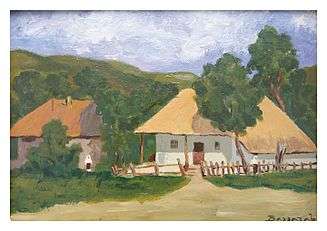

Primăvară pe cheiul Dâmboviței ("Spring on the Dâmbovița", 1934) Case de țară ("Countryside Houses")

Case de țară ("Countryside Houses") Arhanghel ("Archangel"), 1935

Arhanghel ("Archangel"), 1935 Nașterea Căpitanului ("Birth of the Captain")

Nașterea Căpitanului ("Birth of the Captain")

Notes

- (in Romanian) Iurie Colesnic, "În culisele Istoriei. Un pictor căzut la Țiganca", in Timpul, February 8, 2014

- Teacă, p.200. See also Clark, p.192

- Scăiceanu, p.384

- Alexandru D. Broșteanu, "Cronica plastică", in Gândirea, Nr. 4/1936, p.214-15

- Petru Comarnescu, "Note. †Al. Basarab", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 5/1942, p.467-68

- Ioan Victor Vojen, "Prefață pentru o activitate viitoare", in Arta și Omul, Nr. 16–17/1934, p.236–38

- "Caleidoscopul vieții intelectuale. Litere, știință, artă. Premiile și cumpărăturile la Salonul Oficial de desen și gravură", in Adevărul, December 1, 1935, p.2; A. B., "Note și informații", in Arta și Omul, Nr. 16–17/1934, p.264

- Octav Șuluțiu, "Cronica literară: Zoe Verbiceanu, Baladele lui François Villon", in Gândirea, Nr. 3–4/1941, p.195

- Clark, p.192–93

- Clark, p.182, 193

- Clark, p.195

- "Deciziuni. Comisiunea română pentru aplicarea armistițiului. Comunicat", in Monitorul Oficial, Nr. 129/1945, p. 4857

- Valentin Gheorghe, "Activitatea legionarilor dâmbovițeni în timpul monarhiei autoritare carliste (1938–1940)", in Collegium Mediense III. Comunicări Științifice, XII: Istorie, Arheologie, Științe Politice, 2013, p.105

- Petru Comarnescu, "Note. Grupul Grafic", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 2/1940, p.476

- (in Romanian) V. I., Aurel Mărculescu/Aron Marcovici (Piatra Neamț, 1900 – București, 1947), J-Art. Artiști Evrei din România (Center for Monitoring and Combating Antisemitism in Romania & Elie Wiesel National Institute for Studying the Holocaust in Romania)

- Ion Frunzetti, "Grupul Grafic (Sala Dalles)", in Universul Literar, Nr. 40/1940, p. 6

- Clark, p.193; Teacă, p.200

- Ion Vlasiu, "Cronici. Salonul oficial de toamnă", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 12/1940, p.663-64

- Teacă, p.200-01

- Teacă, p.201

- Scăiceanu, p.384; Teacă, passim

- Teacă, p.202

- Nicolae Goga, "Necrolog. Arh. Constantin Joja", in Buletinul Comisiei Naționale a Monumentelor, Ansamblurilor și Siturilor Istorice, Nr. 2/1991, p.58

- Morariu, p.32; Scăiceanu, p.384; Teacă, p.200

- Morariu, p.32

- (in Romanian) Mihai Rădulescu, "George Zlotescu. Un destin sfios și tragic", in Contemporanul, Nr. 5/2008, p.34

References

- Roland Clark, Sfîntă tinerețe legionară. Activismul fascist în România interbelică, Polirom, Iași, 2015. ISBN 978-973-46-5357-7

- (in Romanian) Vasile V. Morariu, "Șerban A. Basarab", in Petre T. Frangopol (ed.), Elite ale cercetătorilor din România: matematică – fizică – chimie, p. 32-4. Editura Casa Cărții de Știință, Cluj-Napoca, 2004

- (in Romanian) Cristian Andrei Scăiceanu, "Activitatea artistului Șerban Zainea la Banca Națională a României", in Acta Terrae Fogarasiensis, II/2013, p. 381-403. Muzeul Țării Făgărașului "Valer Literat", Editura Altip

- (in Romanian) Corina Teacă, "Artă și ideologie: expoziția Munca legionară", in Studii și cercetări de istoria artei. Artă plastică, Serie nouă, tom 1 (45), p. 199–206, Bucharest, 2011