Alexander Macomb (merchant)

Alexander Macomb (1748–1831) was an American fur trader, merchant and land speculator known for purchasing nearly four million acres from the state of New York after the American Revolutionary War. A Loyalist sympathizer, he operated from New York City after the war. His mansion in the city was used by President George Washington for several months in 1790 as the temporary president's mansion.

.jpg)

Macomb had already made a fortune on land speculation in North Carolina, Georgia, and Kentucky, and believed he would make more profit in New York. But, unable to sell the New York land fast enough to meet his debts, he was sent to debtors' prison for a period and never regained his fortune.

Early life and education

Alexander Macomb was born in 1748 in Ballynure, a tiny rural village in County Antrim, northern Ireland to John Macomb, a merchant, and Jane Gordon, both of Scots-Irish descent.[1] Alexander also had a younger brother William and sister. In 1755 the whole family moved to the New York colony, setting in Albany, a center of fur trading with the Iroquois and other Native American tribes.[2]

Macomb and his brother William also became merchants and fur traders, operating around the Great Lakes as far west as Detroit, which had been under British control since 1763. Given their colonial settlement, French-Canadian traders were more numerous in the west, and competition was fierce. On August 27, 1774, Phyn & Ellice, fur traders in Schenectady in the Mohawk Valley, sold its Detroit stock to the Macomb brothers and appointed them as its agents in that post. This was a coup for 26-year-old Alexander and his younger brother.[2]

Career

In Detroit, during the American Revolution, Macomb and his brother William continued their fur trade with British and Native Americans. They conducted a huge volume of business with the British government post at Detroit, supplying the militia as well as the colonial Indian Department. The brothers took a partner because of the volume of their business, and in fall 1781, invested 100,000 dollars in New York currency in the business.[2]

By 1785 Macomb returned to the East, settling in New York City; he followed his partner William Edgar, although they had dissolved the partnership. William Macomb stayed in Detroit, which was still under British rule. He later was elected to a term in the Upper Canada provincial assembly.[3]

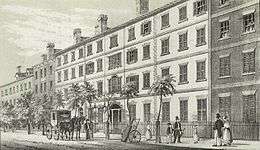

The city was rapidly rebuilding after the war, and men of Loyalist leanings, such as Macomb, were generally not discriminated against.[3] They just wanted to get on with business. Macomb became a successful land speculator and shipping magnate in New York. He purchased large tracts of land in Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina for resale. In 1788, he built a four-story brick city mansion on Broadway one block south of Trinity Church; the house had a 112 feet (34 m) frontage along one side. In part Macomb needed the space for his large household; by 1790 he was a widower with 10 children at home. His household included 25 servants, among them 12 enslaved African Americans. Macomb was the third-largest slaveholder in the city, as by that time slaveholding residents generally owned only a few slaves as domestic servants or skilled labor.[3] New York did not pass legislation for gradual abolition of slavery until the early 19th century.

In 1790 the government of New York City leased Macomb's New York City house to serve as the second presidential mansion of the temporary capital, after the first, the Samuel Osgood House on Cherry Street, proved too small. George Washington occupied the Macomb mansion from February to August 1790. The mansion was later adapted as a landmark hotel.[3]

During this period, Macomb became active in civic affairs, using his expertise to purchase materials and direct the conversion of City Hall into Federal House for the temporary capital. He assisted the state legislature in supervising the construction of a building to house the state archives, and served two terms in the state assembly. Macomb also served as the first treasurer of "New York's first scientific body, the Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures."[3]

In July 1791, Alexander Macomb married again, to the young widow Mrs. John Peter Rucker, née Jane Marshall. They had another seven children together.

That year he purchased his largest tract of land of all, from the State of New York: 3,670,715 acres (14,855 km²), which has since known as "Macomb's Purchase." The tract included much of northern New York, along the St. Lawrence River and eastern Lake Ontario, including the Thousand Islands, and he paid about twelve cents an acre. The state took control of this land after the British ceded their own and Iroquois lands to the United States under terms of the treaty at the end of the war. Four of the six Iroquois tribes had been allied with the British but none was consulted during the treaty negotiations. The state's treaty and sale of this land was never ratified by the US Senate. (Note: In the late 20th century, some of the tribes filed land claims for compensation, claiming that New York state did not have the authority to treat with them, and the land cessions were never ratified by the US Senate. Some of the land claims were upheld by the US Supreme Court.)

The purchase was divided into ten large townships. From this purchase are derived the deeds for all the lands that are now included in Lewis, Jefferson, St. Lawrence, and Franklin counties, as well as portions of Herkimer and Oswego counties.

Contrary to his expectations, Macomb's enterprise was a failure. Sales of land did not keep pace with the due dates for payments. During the Panic of 1792, which further depressed land sales, Macomb was taken to debtor's prison with over $300,000 in debt. He never regained his fortune. As economic conditions improved, some land speculators later made huge amounts of money from their turnover of New York lands.

Marriage and family

.jpg)

On May 4, 1773, Macomb married Mary Catherine Navarre, daughter of Robert de Navarre, the subdélégé of Detroit under the French.[4] They had a large family. His namesake son Major General Alexander Macomb (1782–1841)[5] had an illustrious military career, winning the Battle of Plattsburgh and serving as Commanding General of the United States Army from May 29, 1828, to June 25, 1841. He and five other Macomb sons served in the military during the War of 1812.

Their daughter Jane Macomb married Hon. Robert Kennedy, a Scotsman who was brother of the Marquess of Ailsa.[6] The Kennedys' daughter Sophia-Eliza married John Levett of Wychnor Park, Staffordshire, England.[7]

Their son John Navarre Macomb (07 Mar 1774–09 Nov 1810) married Christina Livingston, granddaughter of Philip Livingston, signer of the United States Declaration of Independence.[8] John Navarre Macomb's children included Colonel John Navarre Macomb, Jr. (1811-1899). Macomb Jr's children included Montgomery M. Macomb (1852-1924), a career United States Army officer who attained the rank of Brigadier General.[9]

When his wife Mary died in 1790, Macomb had 10 children living at home. The next year he married Janet Marshall Rucker, herself a widow.[10][11] They had seven more children, including Elizabeth Maria Macomb (born 7 Jan 1795), who married Thomas Hunt Flandrau, the law partner of Aaron Burr.[12] The Flandraus' eldest son was Charles Eugene Flandrau (1808-1903), a Minnesota political and judicial figure. He was the grandfather of Isabella Greenway (1886-1953), U.S Representative from Arizona.

Alexander Macomb died in the District of Columbia in 1831.

Further reading

- David B. Dill Jr. (September 9, 1990) "Portrait of an Opportunist: The Life of Alexander Macomb". (September 16, 1990) "Macomb's Years in New York City: Wealth and Power". (September 23, 1990) "The Audacity of Macomb's Purchase" and Bibliography, Special to The Times. Watertown Daily Times.

See also

- Alexander Macomb House (New York City)

Notes

- Geo. H. Richards, Memoir of Alexander Macomb (NY: M'Elrath, Bangs & Co., 1833), 14.

- "William Macomb", Becoming Prominent: Regional Leadership in Upper Canada, 1791-1841, McGill-Queens University Press, 1989, p. 213

- David B. Dill Jr. "Portrait of an Opportunist: The Life of Alexander Macomb", Watertown Daily Times, (September 9, 1990). First of a 3-part series

- David Dill, Jr., 'Macomb's Years In NY City Ones of Wealth and Power', Watertown Times, 16 September 1990

- Collections - State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Lyman Copeland Draper, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1879

- Although this son was named after his father, he was not called junior (Jr.), nor was Alexander Macomb the elder called senior (Sr.) They are both known as Alexander Macomb, and neither name is followed by a designation. Richards, p. 14.

- The Peerage of the British Empire as at Present Existing, Edmund Lodge, Anne Innes, Saunders & Otley, London, 1851

- Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, John Burke, H. Colburn, London, 1847

- Kanasas Society of the Sons of the American Revolution application No. 9622 wherein John de Navarre Macomb, Jr. applies for membership under Philip Livingston, Signer of the Declaration.

- Shepard, Frederick J. (1904). Supplement to the History of the Yale Class of 1873. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University. pp. 340–342.

- Saint-Mémin and the Neoclassical Profile Portrait in America, Ellen G. Miles, National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 1994.

- Five Generations: Life and Letters of an American Family, 1750-1900, Margaret Armstrong, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1930.

- Brown, John Howard (1904). The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans. Boston, Biographical Society. Volume IV, F

External links

- Macomb's Mansion (mlloyd.org)