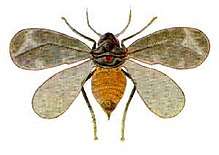

Aleurocanthus spiniferus

Aleurocanthus spiniferus, the citrus spiny whitefly, is an important pest of citrus and tea plants. They are part of the order Hemiptera, and the family Aleyrodidae, where more than 1550 species have been described. A. spiniferus is indigenous to parts of tropical Asia, where it was first discovered in Japan. Since its discovery, it has now spread to numerous continents including Africa, Australia, America, Pacific Islands and Italy. Wherever it is found, it has become a highly destructive pest. Two populations of A. spiniferus have been found according to the plant or crop they infest: the citrus spiny whitefly, as well as the tea spiny whitefly.[1]

| Aleurocanthus spiniferus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hemiptera |

| Suborder: | Sternorrhyncha |

| Family: | Aleyrodidae |

| Genus: | Aleurocanthus |

| Species: | A. spiniferus |

| Binomial name | |

| Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Quaintance, 1903) | |

Distribution

The citrus spiny whitefly has spread to multiple continents including Asia, Africa, Australia, America, Pacific Islands and Italy.[2][3][4] A. spiniferus can be observed on not only citrus plants, but also on rose, grape, peach, pear and guava plants.[5]

Reproduction and life cycle

The eggs are typically laid near each other on a food plants, such as citrus plants, usually on a leaf. Whiteflies have six developmental stages: egg, crawler (1st instars), two sessile nymphal instars (2nd and 3rd instars), pupa (4th instar), and adult. In terms of identification within the Aleyrodidae family, the pupal stage (4th stage) displays the most diagnostic features of the closely related whiteflies.[5]

The initiation and duration of the life cycle, as well as the number of generations per year is highly dependent on the surrounding climate.[5][6] A mild temperature along with high humidity provides an ideal environment for successful growth and development. Kuwana et al. (1927) were able to record about 4 generations per year, with as many as 7 generations that occurred under these ideal laboratory conditions.[6] This study was also able to demonstrate the variability in the life cycle duration.

Ecological impacts

Citrus fruit quality and production are the main target areas researchers are focused on. A. spiniferus causes direct damage, as well as indirect damage to an infested plant.[7] The direct damage includes the weakening of the infested trees due to the ingesting of sap. The second type of damage occurs when the whiteflies excrete honeydew on the leaf surfaces. This in turn promotes the development of sooty mold, which leaves numerous parts of the infested plant such as the leaves, fruit and branches covered with sooty mold. This interferes with photosynthesis, which as a results heavily diminishes overall plant quality.

It has been observed that these pest of citrus plants have also attacked tea plants, such as Camellia sinensis found in Japan. However, researchers found that adult females of the citrus infesting population laid no eggs on the leaves of these tea plants, and only on citrus plants, thus demonstrating the exclusivity of each population.[1]

Management

Many whitefly species have become serious pests, especially when first introduced to new geographical regions, where they typically outcompete other pest species.[3] This is amplified in the absence of natural enemies. The introduction of these natural enemies are considered a biological control. As a result, citrus spiny whitefly outbreaks have been successfully brought under control through biological control. This biological control is typically done so by its parasitoid wasp, E. smithi.[3][6][8][9][10][11] One of the many reasons for the success of this biological control includes its adaptability to new environments, which is aided by its ability to successfully migrate to new areas. Furthermore, its establishment and ability to increase its populations size in these new areas play a major role in their degree of success as a biological control.[3][6][9][10][11]

Colour preference is another method researchers use to monitor population dynamics, or for this instance, to control insect numbers in crop protection.[12][13] Whiteflies have been shown to prefer the colour yellow, therefore methods using this information have been used to create a sticky trap that can aid in controlling these outbreaks.

Overall, chemical controls have been attempted in response to the outbreaks such as spraying pesticides, which can be considered effective however this comes at a cost. These high concentrations of pesticides can result in insecticide resistance, and pesticide in tea drinks causing toxicity hazards to humans.[13] Therefore, due to these factors, generally it has not been shown to be effective on A. spiniferus, including other whiteflies in crop systems.

References

- Kasai, Atsushi; Yamashita, Koji; Yoshiyasu, Yutaka (2010). "Tea-Infesting Population of the Citrus Spiny Whitefly, Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), does not Accept Citrus Leaves as Host Plants". Japanese Journal of Applied Entomology and Zoology. 54 (3): 140–143. doi:10.1303/jjaez.2010.140. ISSN 0021-4914.

- El Kenawy, Ahmed; Baetan, Raul; Corrado, Isabella; Cornara, Daniele; Oltean, Ion; Porcelli, Francesco (2015). "Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Quaintance) (Orange Spiny Whitefly, Osw) (Hemiptera, Aleyrodidae) Invaded South of Italy". Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Agriculture. 72 (1). doi:10.15835/buasvmcn-agr:11148. ISSN 1843-5386.

- Kanmiya, K., Ueda, S., Kasai, A., Yamashita, K., Sato, Y., & Yoshiyasu, Y. 2011. Proposal of new specific status for tea-infesting populations of the nominal citrus spiny whitefly Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Zootaxa, vol 2797: 25-44.

- Tang, Xiao-Tian; Tao, Huan-Huan; Du, Yu-Zhou (2015). "Microsatellite-based analysis of the genetic structure and diversity of Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from tea plants in China". Gene. 560 (1): 107–113. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2015.01.050. ISSN 0378-1119. PMID 25662872.

- Gyelshen, Jamba; Hodges, Amanda (2005). "Orange Spiny Whitefly". Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- Kuwana I, Ishii T. 1927. On Prospaltella smithi Silv., and Cryptognatha sp., the enemies of Aleurocanthus spiniferus Quaintance, imported from Canton, China. Review of Applied Entomology, vol 15: 463.

- Chen, Zhi-Teng; Mu, Li-Xia; Wang, Ji-Rui; Du, Yu-Zhou (2016). "Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Citrus Spiny Whitefly Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Quaintance) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae): Implications for the Phylogeny of Whiteflies". PLOS ONE. 11 (8): e0161385. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1161385C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161385. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4995055. PMID 27551782.

- Kishida, Akira; Kasai, Atsushi; Yoshiyasu, Yutaka (2010). "Oviposition and Host-Feeding Behaviors of Encarsia smithi on a Tea-Infesting Population of the Citrus Spiny Whitefly Aleurocanthus spiniferus". Japanese Journal of Applied Entomology and Zoology. 54 (4): 189–195. doi:10.1303/jjaez.2010.189. ISSN 0021-4914.

- Uesugi, R.; Sato, Y.; Han, B.-Y.; Huang, Z.-D.; Yara, K.; Furuhashi, K. (2016). "Molecular evidence for multiple phylogenetic groups within two species of invasive spiny whiteflies and their parasitoid wasp". Bulletin of Entomological Research. 106 (3): 328–340. doi:10.1017/s0007485315001030. ISSN 0007-4853.

- Berg, M. A.; Greenland, J. (1997). "Classical biological control of Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Hem.: Aleyrodidae), on citrus in Southern Africa". Entomophaga. 42 (4): 459–465. doi:10.1007/bf02769805. ISSN 0013-8959.

- Van Den Berg, M. A.; Hoppner, G.; Greenland, J. (2000). "An Economic Study of the Biological Control of the Spiny Blackfly, Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), in a Citrus Orchard in Swaziland". Biocontrol Science and Technology. 10 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1080/09583150029350. ISSN 0958-3157.

- Ping, P., Min, T., Yujia, H., Qiang, L., Shanglun, H., Min, D., Xiang, H., & Ying, Z. 2010. Study on the effect and characters of yellow sticky trap sticking Aleurocanthus spiniferus and Empoasca vistis in tea garden. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences, vol 23: 87-90.

- Wang, Y.; Gao, N.; Shi, L.; Qin, Z.Y.; He, P.; Hu, D.Y.; Tan, X.F.; Chen, Z. (2015). "Evaluation of the attractive effect of coloured sticky traps for Aleurocanthus spiniferus (Quaintance) and its monitoring method in tea garden in China". Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research. 47 (3): 86. doi:10.4081/jear.2015.4603. ISSN 2279-7084.