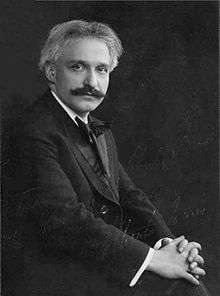

Alberto Jonás

Alberto Jonás (June 8, 1868, Madrid – November 10, 1943, Philadelphia) was a Spanish pianist, composer, and piano pedagogue. Although not much is known about his life, as a pianist he was regarded as a virtuoso on the level of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Moriz Rosenthal, Leopold Godowsky, Józef Hofmann, and Josef Lhévinne . He also ranked, during the 1920s and 30s, among the greatest and most sought-after keyboard pedagogues of the time.

Life and early career (Madrid, 1868 – 1886)

Born in Madrid to German parents Julius Jonas, a businessman, and Doris Sachse, his musical talents were recognized at an early age. King Alfonso XII of Spain received the young child in a private audience at the Royal Palace of Madrid in 1880 and Jonás was immediately hailed as a prodigy. He initially studied at the Madrid Royal Conservatory with Manuel Mendizábal (1817–1896) in piano (Mendizábal had been Isaac Albéniz's piano teacher) and Ciriaco Olave in organ, graduating at the age of 12, in 1880. For the next six years he travelled and lived in Belgium, England, Germany, and France studying business, in accordance to his parents' desires for a career in finance, and also giving some public performances. At this time, Jonás started also to become a polyglot, mastering fluently the French, Russian, German, English, and Spanish languages.

Brussels, 1886–1890

In 1886, at the age of 18 and against the will of his parents, who kept trying to dissuade him from pursuing a career as a concert pianist, he entered the Brussels Conservatory, where he studied for four years with noted Franz Liszt pupil Arthur De Greef and composition with François-Auguste Gevaert. According to the Annuaire du Convervatoire Royal de Musique de Bruxelles, he won the coveted First Prize (Premier Prix) of the Brussels Conservatory, in the Piano Section, in 1888, playing Moscheles' G Minor Piano Concerto, a Prelude and Fugue by Bach, and the Caprice Sure Des Airs de Ballet d'Alceste de Gluck, by Saint-Saens. He later won an Honorable Mention in Harmony in the year 1890, the final year of his graduation.

St. Petersburg, Germany, Austria, 1890–1893

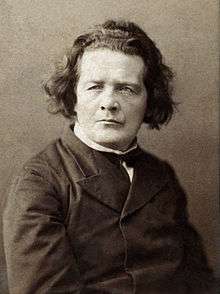

Upon graduating from Brussels in 1890, he entered the first international Anton Rubinstein Competition, which was being held at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Even though he did not win the coveted First Prize in piano (it went to Nikolay Dubasov), he nevertheless made an extraordinary impression on Anton Rubinstein, who immediately invited him to be one the handful of pianists who had the privilege of being his students. He then worked with Rubinstein in St. Petersburg for the next three years. During his sojourn there, he became a recognized pianist and teacher, and soon befriended fellow Rubinstein students, Józef Hofmann, Felix Blumenfeld, and Teresa Carreño, who all held his playing in high esteem. During this period he also met Ignacy Jan Paderewski, who acted as a mentor and gave him some lessons (in particular on his own Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17, which Jonás would later often perform) and encouraged him to continue his studies in music. In 1891 he made his debut in Berlin as a soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic under Hans von Bülow, receiving rave reviews.

United States 1893–1904

In 1893 he moved to New York, soon making a debut with the Symphony Society of New York in Carnegie Hall playing the Paderewski Concerto conducted by Walter Damrosch. In 1894, he was named professor at the Music School of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, later becoming President and Director of the Michigan Conservatory of Music in Detroit, a post he held until 1904. In 1897 he debuted with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Emil Paur, again with the Paderewski concerto. He also concertized in Canada, Mexico and Cuba at this time. On December 20, 1899, he married German pianist Elsa von Grave in Ann Arbor, who although born in Cologne had been a pupil of Hans von Bülow at the Munich Conservatory and was the daughter of the German Baroness Rosalie von Grave and the German Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Mortimer, Baron von Grave (1824–1896), a captain in the Prussian army. Elsa von Grave had emigrated to the US in 1894, one year after Jonás, and they most likely met in Ann Arbor on that same year.

Berlin 1904–1914

In 1904 Jonás decided he would return to Europe, settling in Berlin, where he soon became one of the most respected piano teachers. There he soon became a professor at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory and befriended Leopold Godowsky, Karl Klindworth, James Kwast and Moritz Moszkowski, who were also teachers and performers there. World War I caused him to return to New York, where he finally settled. It is unclear whether Alberto Jonás divorced Elsa von Grave or if she died in the war. By 1914, he was no longer in a marriage to her and began a relationship with an American pianist of German descent, Henrietta Gremmel (1888-1964), whom she later married in 1921. She was from Muscatine, Iowa, the daughter of a German immigrant from Hannover who had established a tobacco business in Muscatine. She was 20 years younger than Alberto Jonas.

United States 1914–1943

In October 17, 1914, he returned from war-torn Europe to New York, in the company of pianist Henrietta Gremmel (1888-1964), whom he would later marry. From 1914 until his death in 1943, he lived in a New York apartment on the Upper West Side (19 West 85th Street), his apartment becoming a mecca for talented students and pianists from all over the world. Soon, Jonás also became professor at the Combs College of Music in Philadelphia, where he kept a small apartment as well, and the Von Ende School of Music in New York. Alberto Jonas died on November 10, 1943, in Philadelphia.

Master School of Modern Piano Playing and Virtuosity

It is during his period in New York when Jonás had the unprecedented idea of starting a correspondence with all of the great musicians and pianists he had met throughout his life as a wandering musician, asking them personally to collaborate with their own ideas on pianism towards the publication of a treatise on piano playing that would include the main currents in modern virtuosity. The pianists even agreed to write their own technical exercises specifically for Jonás book, as well as sharing their own ideas on technique, pedalling, fingering, practicing methods, phrasing, memorizing, etc., and also taking exclusive photographs of themselves and their hands playing in order to illustrate some points.

In the early 1920s he started putting together all the material he had amassed from the correspondence and began writing what he would later title Master School of Modern Piano Playing and Virtuosity, in seven volumes. It took him seven years to complete the vast undertaking (1922–1929), which in its final formed featured the unique distinction of having the collaboration of practically all the greatest living piano virtuosi. The final contributors were Arthur Friedheim, Ignaz Friedman, Vasily Safonov, Ferruccio Busoni, Katharine Goodson, Leopold Godowsky, Alfred Cortot, Rudolph Ganz, Wilhelm Backhaus, Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler, Ernő Dohnányi, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Josef Lhévinne, Isidor Philipp, Moriz Rosenthal, Emil von Sauer, Leopold Schmidt, and Zygmunt Stojowski, and included excerpts from more than one thousand examples drawn from the entire piano literature in order to illustrate specific points.

In breadth of scope, originality, and clearness of execution, the book is unprecedented. It was finally published in 1929 by Carl Fischer Music in New York. Busoni considered it "the most monumental work ever written on piano playing" in seven volumes:

Book I: Finger Exercises Book II: Scales Book III: Arpeggios Book IV: Complete School of Double Notes Book V: Octaves, Staccato, and Chords Book VI: The Artistic Employment of the Piano Pedals Book VII: Exercises for Fingers, Wrists, and Arms Away From the Piano, Phrasing, Embellishments in Music

Lhévinne called it "the greatest and most valuable work on the subject", and Rosenthal called it a "Master-Work" (meisterarbeit). It was also admired by Sergei Rachmaninoff, who mentioned it in some of his letters.

Reception

Due to the impact of the Great Depression and World War II on the publishing industry in America, the Master School was never reprinted and quickly went out of print. The author and his ideas became somewhat forgotten after his death, but there are still pianists and teachers who use volumes of the "Master School" in their pedagogy. Even though he is the most important Spanish writer on pianism, he is practically unknown in his native country (where the Master School has never been published).

Some of Alberto Jonás's piano students include Pepito Arriola, Ellen Ballon, Anis Fuleihan, Eugenia Buxton, Vincent Persichetti, Eloise Wood, Daniel Jones, Lewis L. Richards, David Earl Moyer, Leonard Heaton, Alfred Lucien Calzi, Elizabeth Zug, Reah Sadowsky, and Louis Loth.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alberto Jonás. |

- Saleski, Gdal (1927) Famous Musicians of a Wandering Race, pp. 328–330

- Great Pianists on Piano Playing. Edited by James Francis Cooke.

- Brower, Harriete (2003) Piano Mastery. The Harriete Brower Interviews. Edited by Jeffrey Johnson, Dover, New York.

- Busoni: Selected Letters. Edited by Antony Beaumont, Butler & Tanner, London, 1987, p. 195

- Dubal, David: The Art of the Piano

- Dubal, David: Reflections from the Keyboard: the world of the concert pianist.

- Lee-ling Chang, Anita: The Russian school of advanced piano technique: its history and development from the 19th to 20th century. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texaus, Austin, 1996.

- Alba González, Amanda Judith (2007) Escuela magistral de la virtuosidad pianística moderna de Alberto Jonás y sus ejercicios técnicos originales convergencia de la ejecución pianística y el estudio teórico de la técnica. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

- University of Michigan. School of Music (1892). Calendar of the University School of Music. pp. 5–.