Alaska marmot

The Alaska marmot (Marmota broweri), also known as the Brooks Range marmot[2] or the Brower's marmot,[3] is a species of rodent in the family Sciuridae. It is found in the scree slopes of the Brooks Range, Alaska. They eat grass, flowering plants, berries, roots, moss, and lichen.[4] These marmots range from about 54 centimetres (21 in) to 65 centimetres (26 in) in length and 2.5 kilograms (5.5 lb) to 4 kilograms (8.8 lb) in weight.[5] Alaska celebrates every February 2 as "Marmot Day," a holiday intended to observe the prevalence of marmots in that state and take the place of Groundhog Day.[6]

| Alaska marmot | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Sciuridae |

| Genus: | Marmota |

| Species: | M. broweri |

| Binomial name | |

| Marmota broweri Hall & Gilmore, 1934 | |

| |

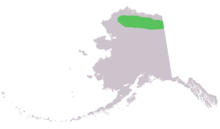

| Range of Marmota broweri in Alaska. Its range also extends slightly into Canada. | |

Etymology

Originally Marmota broweri was perceived as a synonym for M. caligata,[7][8] but this was soon proven false when evidence was found that corroborated M. broweri as a unique species.[9][10][11] Cytochrome b sequences were used to verify that M. broweri as its own distinct species.[11]

History

Marmota broweri are sometimes hunted by Alaskan Natives for food and their warm fur.[12] An Eskimo hunter would spend all summer hunting marmots to make a parka, as it takes about 20 marmot pelts to make a single parka.[12]

Marmot Day is essentially Alaska's version of Groundhog Day.[13] Sarah Palin signed a bill in 2009 to officially make every February 2 Marmot Day.[13] The bill, introduced by Senator Linda Menard, said, "It made sense for the marmot to become Alaska's version of Punxsutawney Phil, the Pennsylvania groundhog famed for his winter weather forecasts."[13] She did not expect marmots to have any weather forecasting duties but rather hoped that the state would create educational activities regarding the marmot.[13]

Status

The status of Alaska marmots is not well known due to the difficulties in finding them in their natural habitats.[5] According to IUCN, the Alaska marmot is considered to be of "least concern" status, signifying relatively low concern in terms of the dangers they face.[12] Although Alaska marmots may be hunted, their population is stable and not at risk for endangerment.[12] In fact, the Alaska marmot has been declared the least threatened species of marmot.[3]

Description

General

Alaskan marmots are mammals.[12] They possess a short neck, broad and short head, bushy tail, small ears, short powerful legs and feet, densely furred tail, and a thick body covered in coarse hair.[4] Adult Alaska marmots’ fur on their nose and the dorsal part of their head are usually of a dark color.[12] Their feet may be light or dark in color.[4] M. broweri have tough claws adapted for digging,[4] however the thumbs of their front limbs do not have these claws but flat nails instead.[12] Their body size is highly variable due to hibernation cycles.[14] For males, the average total length is 61 centimetres (24 in) and the average weight is 3.6 kilograms (7.9 lb).[2] Adult females are slightly smaller, having an average length of 58 centimetres (23 in) and 3.2 kilograms (7.1 lb).[2]

Anatomical distinctions

The retina of the eye of Alaska marmots is entirely lacking of rods, making their night vision quite poor.[3] They also lack the fovea of the eye, making their visual acuity much worse than other rodents.[3] The location of their eyes makes their field of vision very wide, sideways and upward.[3] All of their teeth will grow throughout their lifetime, resembling sharp rodent incisors.[12] There is a single pair of incisors in each jaw.[3]

Ecology

Location and distribution

In terms of global distribution, the Alaska marmot is nearctic.[5] Current distribution of the Alaska marmot include the Brooks Range, Ray Mountains, and Kokrines Hills.[15] They exist in the mountains that lie north of the Yukon and Porcupine rivers in central and northern Alaska.[5] However, there have been reports of Alaska marmots in the Richardson Mountains in the northern Yukon Territory but these sightings have not yet been confirmed.[5][16]

Alaska marmots are found scattered throughout Alaska as small colonies each consisting of various families.[17] Their locations have been documented in the Brooks Range from Lake Peters to Cape Lisburne and Cape Sabine that lies westward.[18] There have been sightings of marmots near rivers in the Northern Baird mountains and in the Mulik Hills.[19] They have also been sighted near copter Peak in the DeLong Mountains.[20] Species have also been secured south of the Brooks Range in the Spooky Valley and in the Kokrines Hills.[5]

Habitat

The Alaska marmots live in polar habitats including the terrestrial tundra and mountain biomes.[12] They are located at elevations of about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) to 1,250 metres (4,100 ft).[12] They are often found in boulder fields, rock slides and outcrops, terminal moraines, and Talus slopes[4] in Alpine tundra with herbaceous forage.[5] They are often found on mountain slopes surrounding lakes, and are found less commonly away from a lake.[21] To create their shelter Alaska marmots burrow into permafrost soil containing tundra vegetation, and within ten meters a rocky ledge serves as an observation post.[12] Alaska marmots live in relatively permanent winter dens that serve as a marmot colonies’ shelter for at least twenty years.[3] A colony is essentially several individual family burrows built in close proximity to one another.[4] Their dark fur serves as a mild camouflage in their rocky environments.[12] Wind is also very important to an Alaska marmot's habitat and climate because it removes annoying mosquitoes.[4] If there are large amounts of mosquitoes in the area due to a lack of wind, marmots will actually remain in their dens until the climate changes and the number of mosquitoes decrease.[12]

Diet

Tundra vegetation that grows on mountain sides are the primary nutrition source and they include; grasses, forbs, fruits, grains, legumes, and occasionally insects.[2][3] M. bromeri must eat large amounts of the arctic plants because they are low in nutritional value and for preparation of hibernation.[2] Alaska marmots are typically known as omnivores but they have also been described as insectivorous, folivorous, frugivorous, and granivorous.[3]

Predation

Common Alaska marmot predators include; wolverines, gray wolves, grizzly bears, coyotes, foxes and eagles (the main predator for young marmots).[4]

Dangers

Although dangers of direct human disturbance are minimal, climate dangers pose a real problem.[3] The Alaska marmot is arguably the most sensitive of the 14 marmot species to anthropogenic disturbances, including climate change.[3]

Behavior

Social behavior

Alaska marmots are very social, living in colonies of up to 50 while all sharing a common burrow system.[3] Marmots typically have their own personal den, while the young live with their mother and the father lives in a nearby den.[12] Especially in large colonies, the Alaska marmots utilize sentry duty rolls that are periodically rotated. A sentry marmot will alert the colony via a two-toned, high-pitched warning call (marmot vocalizations) if there is a predator in the area.[4] The older marmots will defend and keep a lookout for predators while the young play.[12] Solely dirt dug dens provides limited protection, but a den built under rocks and boulders can prevent the risk from large animals, such as grizzly bears, who can dig marmots out of their dirt dug dens.[12]

M. broweri will mark their territory by secreting a substance from face-glands and rubbing the sides of their face on rocks around their den and various trails.[11] Alaska marmots also enjoy sunbathing and spending a large amount of time in personal grooming.[3]

Hibernation

M. broweri is one of the longer hibernating marmots, being documented to do so up to eight months annually.[3] Alaska marmots accumulate a thick fat layer by late summer to sustain them throughout the winter hibernation.[4] Alaska marmots are active until snow begins to fall, in which they will go to their hibernacula from around September until June.[2] Alaska marmots have special winter dens with a single entrance that is plugged with a mixture of dirt, vegetation, and feces during the entire winter hibernation period.[4] They are built on exposed ridges that thaw earlier than other areas, and the entire colony stays within the den from September until the plug melts in early May.[4] They then resettle in their dens in family units to communally hibernate for the winter.[14] Communal hibernation may be an adapted strategy to reduce metabolic cost while trying to keep their body temperatures above freezing.[14] In order to seal their hibernaculum off from the elements, they will plug their entrance with hay, earth, and stone.[12] During hibernation many of their body functions decrease; body temperature (averages between 4.5 °C (40.1 °F) and 7.5 °C (45.5 °F)), heart rates, respiratory rates,[12][14] and metabolic rates. Alaska marmot hibernation is not continuous because they will awaken every three or four weeks in order to urinate and defecate.[3][14] Inside the hibernaculum den, the Alaska marmot has shown long-term hibernation adaptions by their ability to tolerate high CO2 levels and low O2 levels.[22] As an adaption to the Arctic environment and permanently frozen ground, Alaska marmots breed prior to emerging from the winter den.[4] The Alaska marmots will generally emerge from the den during the first 2 weeks of May.

Reproductive

Male Alaska marmots are polygynous, mating with the monogamous females living on their territory.[12] They are seasonal iteroparous and viviparous breeders that mate once per in the early spring and give birth about six week later with litter sizes ranging from 3 to 8 and an average litter size of 4-5.[12] The male and female Alaska marmots are involved in both raising and protecting the pups in their natal burrow.[12] In both sexes sexual reproductive behaviors are stimulated by odors released from anal scent glands.[12] Before birthing, the female will first close her den off and then she will give birth alone.[12] The Gestation period is about 5–6 weeks.[12] Newly born Alaskan marmots are altricial;[12] hairless, toothless, blind[4] and are quite vulnerable to predators. After about six weeks young marmots have thick, soft fur and they begin to temporarily leave the den.[12] They will go through 3 coats in their first year until their final one, which resembles adult Alaska marmots.[12] They will hibernate and live with their parents at least one year, they will be fully-grown after two years and reach sexual maturity from 2 to 3 years.[4][12] Marmots life span are not known but it is believed to be about 13–15 years.[12]

Captive rearing

M. broweri has been reported to have been successfully reared in captivity and reintroduced into the wild (however there have been cases where captive rearing led to high rates of mortality).[3]

Evolution and fossils

The Alaska marmot has ancestry to the Pleistocene epoch.[11] There have been no known fossils of Marmota broweri.[5] However, the M. flavescens fossil recovered from the Late Pleistocene age from the Trail creeks caves on the Seward Peninsula[23] is speculated to be an incorrect identification of the fossil[5] This fossil could be M. broweri.[5]

The evolutionary lineages of the 14 marmot species distributed across the Holarctic are relatively ambiguous.[24] Cytochrome b sequences indicated that M. broweri is most likely related to M. caudata, cenzbieri, marmota, and monax.[24] In support to the cytochrome b results, experimentation involving mitochondrial DNA has suggested that M. broweri is most likely related to M. caudata and M. menzbieri.[3] However, morphological data have linked M. broweri to M. camtschatica.[3] In addition, somatic chromosome analysis of marmots, ecological data and behavioral data have shown that there is a link between M. broweri and M. caligata.[25] The conflicting data pertaining to phylogeny creates inconsistent marmot lineage relationship hypotheses.

References

- Linzey, A. V., Hammerson, G. (NatureServe), & Cannings, S. (NatureServe) (2008). "Marmota broweri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "North American Mammals: Marmota Broweri". Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Hubbart, Jason A. (2011). "CURRENT Understanding of the Alaska marmot (Marmota Broweri): A Sensitive Species in a Changing Environment". J Biol Life Sci: 6–13. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- Curby, Catherine. "Marmot.Wildlife Notebook Series(On-line)" (PDF). Alaskan Department of Fish & Game. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- MacDonald, S. O. (2009). Recent Mammals of Alaska. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska. pp. 65–66.

- The Associated Press. "Alaska to celebrate its first Marmot Day," Archived 2010-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. Feb. 1, 2010. Accessed Feb. 1, 2010.

- Hall, E.R.; R.M. Gilmore (1934). "Marmota caligata broweri, a new marmot from northern Alaska". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 48: 57–59.

- Hall, E.R. (1981). The mammals of North America. New York: Wiley-Inter science.

- Rausch, R. L.; V. R. Rausch (1965). "Cytogenic evidence for the specific distinction of an Alaskan marmot, Marmota broweri Hall and Gilmore (Mammalia: Sciuridae)". Chromosoma (Berlin). 16 (5): 618–623. doi:10.1007/bf00326977.

- Hoffmann, R. S.; J.W. Koeppl; C.F. Nadler (1979). "The relationships of the amphiberingian marmots (Mammalia: Sciuridae)". University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Occasional Paper. 83: 1–56.

- Rausch, R. L.; V.R. Rausch (March 1971). "The somatic chromosomes of some North American marmots (Sciuridae), with remarks on the relationships of Marmota broweri Hall and Gilmore". Mammalia. 35: 85–101. doi:10.1515/mamm.1971.35.1.85. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Rasmussen, J. "Marmota Broweri (On-line)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Marmot Day: Alaska Adopts Its Own Version Of Groundhog Day". Green News: The Huffington Post. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Lee, T. N.; B. M. Barnes; C. L. Buck (2009). "Body Temperature Patterns during Hibernation in a Free-living Alaska marmot (Marmota Broweri)". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 21 (3–4): 403–13. doi:10.1080/08927014.2009.9522495.

- Gunderson, Aren M.; Brandy K. Jacobsen; Link E. Olson (2009). "Revised Distribution of the Alaska Marmot, Marmota broweri, and Confirmation of Parapatry with Hoary Marmots". Journal of Mammalogy. 90 (4): 859–869. doi:10.1644/08-mamm-a-253.1.

- Youngman, P. M. (1975). "Mammals of the Yukon Territory". National Museums of Canada, Ottawa, Publications in Zoology. 10: 1–192.

- Hoffmann, R. S. (1999). D. E. Wilson; S. Ruff (eds.). "Alaska Marmot, Marmota broweri". The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals: 393–395.

- Childs, H. E. (1969). "Birds and mammals of the Pitmegea River region". Cape Sabine, Northwestern Alaska, Biological Papers of the University of Alaska: No. 10.

- Dean, F. C.; D. L. Chesemore (1974). "Studies of birds and mammals in the Baird and Schwatka mountains". Alaska. Biological Papers of the University of Alaska: No. 15.

- Macdonald, S. O.; J. A. Cook (2002). "Mammal inventory of Alaska's National Parks and Preserves". Northwest Network: Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, Cape Krusenstern National Monument, Kobuk Valley National Park, Noatak National Preserve, National Park Service Alaska Region, Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report 2001.

- Bee, J. W.; E.R. Hall (1956). Mammals of northern Alaska on the Arctic slope. 8. University of Kansas Museum of Natural History: Miscellaneous Publication. pp. 1–309. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- Williams, D.; R. Rausch (1973). "Seasonal Carbon Dioxide and Oxygen Concentrations in the Dens of Hibernating Mammals (Sciuridae)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 44 (4): 1227–235. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(73)90261-2.

- Yesner, D.R. (2001). "Human dispersal into interior Alaska: Antecedent conditions, mode of colonization, and adaptions". Quaternary Science Reviews. 20 (1–3): 315–327. doi:10.1016/S0277-3791(00)00114-1.

- Steppan, Scott; et al. (1999). "Molecular Phylogeny of the Marmots (Rodentia: Sciuridae): Tests of Evolutionary and Biogeographic Hypotheses". Systematic Biology. 48 (4): 715–734. doi:10.1080/106351599259988. PMID 12066297. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- Rausch, Robert; Virginia Rausch (1971). "The Somatic Chromosomes of Some North American Marmots (Sciuridae), with Remarks on the Relationships of Marmota Broweri Hall and Gilmore". Mammalia. 35 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1515/mamm.1971.35.1.85.

External links

![]()