Ahmad ibn Isa al-Shaybani

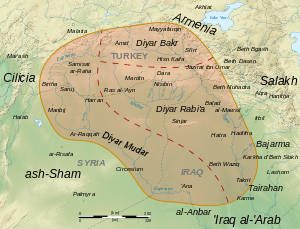

Ahmad ibn Isa al-Shaybani (Arabic: أحمد بن عيسى الشيباني) (died 898), was an Arab leader of the Shayban tribe. In 882/3 he succeeded his father, Isa ibn al-Shaykh, as the virtually independent ruler of Diyar Bakr, and soon expanded his control over parts of southern Armenia as well. He gained control over Mosul as well in 891/2, but faced with a resurgent Abbasid Caliphate, he was deprived of the city and forced into a position of vassalage by Caliph al-Mu'tamid. Shortly after his death in 898, the Caliph deprived his son and heir, Muhammad, of the last territories remaining under the family's control.

Life

Ahmad was the son of Isa ibn al-Shaykh al-Shaybani. In the 860s, exploiting the turmoil of the "Anarchy at Samarra", which paralysed the Abbasid Caliphate and encouraged separatism in the provinces, Isa had for a short time made himself master of a de facto independent bedouin state in Palestine. Eventually he was compelled to leave Palestine and assume the governorship of Armenia, but unable to enforce his authority against the local princes, he abandoned the province in 878 and returned to his native Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia). There he established himself as the ruler of Diyar Bakr, with Amid as his capital.[1][2][3]

At Isa's death in 882/3, Ahmad succeeded his father. An ambitious man, he used his position as the virtually independent governor of Diyar Bakr to extend his influence in both the rest of the Jazira and northwards into Armenia.[4] Although unlike his father he held no official post on behalf of the Caliphate in Armenia, in 887 he was sent by Caliph al-Mu'tamid to confer the royal crown to the Bagratid prince Ashot I, thereby establishing a practically independent Armenian kingdom.[4]

In the Jazira, like his father before him, Ahmad was opposed by the Turkish ruler of Mosul, Ishaq ibn Kundajiq, who had been recognized by the Caliph as governor of the Jazira. It was only after Ibn Kundajiq's death in 891/2 that Ahmad managed to expand his domains, seizing Mardin and eventually Mosul itself, driving out Ibn Kundajiq's son Muhammad.[2][5] His success did not last long, for in 893, the energetic new Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tadid campaigned in the Jazira and placed Mosul under direct caliphal administration, limiting the Shaybanids to their original province of Diyar Bakr.[2][4] In view of the resurgence in Abbasid power under al-Mu'tadid, Ahmad endeavoured to win the Caliph's favour to secure his position. Thus, upon the Caliph's request, he dispatched Ibn Kundajiq's treasure to Baghdad and included many presents of his own, as well as a Kharijite rebel he had captured.[4] Al-Mu'tadid's cousin and panegyrist, Ibn al-Mu'tazz, celebrated Ahmad's submission and claimed that he "contemplated crossing into Byzantine territory and becoming a Christian", but Marius Canard considers the latter doubtful.[4]

In the direction of Armenia, Ahmed began expanding in c. 890: he imprisoned Abu'l-Maghra ibn Musa ibn Zurara, the emir of Arzen in southern Armenia, who was related to the Bagratids and had even secretly become a Christian himself, and annexed his territory to his own.[4][6] Taking advantage of the war between Ashot I's successor Smbat I and the Sajid Muhammad al-Afshin, Ahmad launched an invasion of the principality of Taron, capturing Sasun. After the death of prince David, Ahmad engineered the murder of his nephew and successor, Gurgen, and managed to seize the entire principality (895 or early 896).[4][6]

As the princes of Taron were members of the royal Bagratid house, this action embroiled Ahmad in a direct conflict with King Smbat I, who now requested of the Shaybanid emir to vacate Taron, in exchange for securing his nomination as the Caliph's representative governor in Armenia.[4][6] Ahmad refused, and Smbat assembled a huge army (reportedly 60,000 or even 100,000 men according to medieval sources) to march against him. Smbat's campaign failed, however, due to the treachery of Gagik Apumrvan Artsruni, regent of Vaspurakan: Smbat's army relied on Gagik as their guide, and he led them deliberately along difficult roads over the mountains, so that when they arrived in Taron, the Armenian army was exhausted. With Gagik working to undermine the soldiers' morale, the royal army was almost destroyed in the following battle, and King Smbat himself barely managed to escape.[4][7]

Ahmad died in 898, and was succeeded by his son, Muhammad, who ruled briefly until, in the next year, al-Mu'tadid put an end to Shaybanid power and placed Diyar Bakr under his direct administration.[2][4] In Taron, power was taken over by a cousin of the murdered prince Gurgen, Grigor.[8]

Legacy

As "rulers by usurpation" (ʿalā sabīl al-taghallub), Ahmad and his father are judged harshly by contemporary Muslim historians, but according to M. Canard, "in the disturbed period in which these Mesopotamian Arabs lived, they were no worse in their behaviour than the other soldiers of fortune of the Abbasid regime".[4] Like all the Shayban, however, Isa and Ahmad too were esteemed for the quality of their Arabic poetry.[9] The historian al-Mas'udi also wrote a detailed account of Ahmad's life in his Akhbar al-zaman, now lost.[4]

References

- Canard (1978), pp. 88–90

- Kennedy (2004), p. 182

- Ter-Ghevondyan (1976), pp. 25–26, 29, 56–57

- Canard (1978), p. 90

- Canard (1978), pp. 89–90

- Ter-Ghevondyan (1976), p. 63

- Ter-Ghevondyan (1976), pp. 63–64

- Ter-Ghevondyan (1976), p. 66

- Bianquis (1997), pp. 391–392

Sources

- Bianquis, Thierry (1997). "S̲h̲aybān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 391–392. ISBN 90-04-10422-4.

- Canard, Marius (1978). "ʿĪsā b. al-S̲h̲ayk̲h̲". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 88–91. OCLC 758278456.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976) [1965]. The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Translated by Nina G. Garsoïan. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. OCLC 490638192.